TCM Diary: Olivia de Havilland

FILM COMMENT and Turner Classic Movies are pleased to announce a new editorial collaboration: “Film Comment Picks.” Each month, the team at FILM COMMENT will publish new essays inspired by films, directors, or actors featured in TCM’s programming.

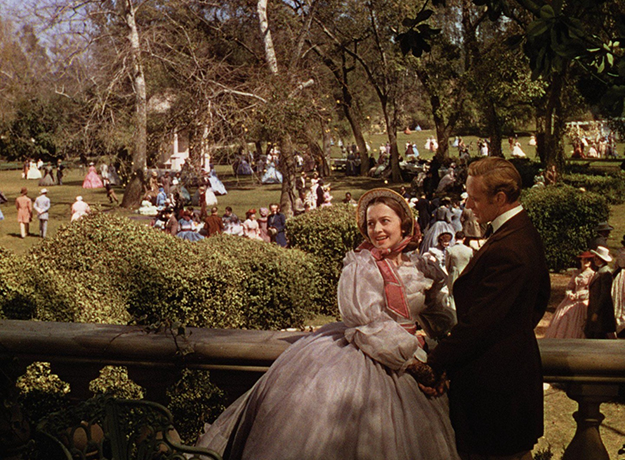

Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind’s Melanie Hamilton may have been “a paleface, mealy-mouth ninny” according to her sister-in-law Scarlett, but she, too, was a survivor. So is the actress who breathed life into the role, Olivia de Havilland, who has now survived all but one of her 42 credited co-stars. This month’s featured star on Turner Classic Movies, de Havilland celebrates her 100th birthday on the first of the month. Nearly typecast as passive and afflicted heroines, she took control of her career and, as evidenced in her award-winning roles in To Each His Own and The Heiress, explored the condition of suffering as both ennobling and corruptive.

Born in Tokyo, de Havilland grew up in California with her sister Joan (who would later act under the name Joan Fontaine), and made her film debut while still a teenager, in Max Reinhardt’s phantasmagoric 1935 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In it she played the ingénue role of Hermia, which she’d essayed earlier in Reinhardt’s Hollywood Bowl staging. With Mendelssohn music, ballet interludes, and a pubescent Mickey Rooney as Puck, it’s one of the most atypical works released by Warner Brothers, purportedly the grittiest of the major studios, and while not a financial success it earned de Havilland good notices and a lucrative contract.

Subsequent roles would capitalize on her wholesome beauty and amiable demeanor, including eight pairings with Errol Flynn, most iconically as a winsome Maid Marian to his swashbuckling bandit in The Adventures of Robin Hood. She found these jobs by and large unchallenging, so when David O. Selznick wrote in a memo to a colleague, “I would give anything if we had Olivia de Havilland under contract to us so that we could cast her as Melanie,” the time to break out of her tower had arrived. Drawn to the selfless, sweet-natured role of “Melly” and not—like every other actress in Hollywood—to the tempestuous Scarlett, de Havilland enlisted the wife of studio head Jack Warner to persuade her husband to loan her to MGM. She earned her first Oscar nomination for what The New York Times deemed her “gracious, dignified, tender gem of characterization,” and the dimensions of the role—alluring but approachable, soft-spoken but pensive, weak of body but strong of heart—would form the outline of the Olivia de Havilland mold.

The Adventures of Robin Hood

Melanie’s on-screen victimhood doubtlessly influenced de Havilland’s later assignments. Martyrdom became a core component of her image, especially when the size and complexity of her roles increased; witness her adoring schoolteacher enticed into a green card marriage by Romanian cad Charles Boyer in Hold Back the Dawn. (She lost the Best Actress Oscar that year to Fontaine for Hitchcock’s Suspicion.) But the actress refused to play the victim off-screen, frequently balking at the one-dimensional swooners and sighers offered her by the studio. “I was really restless to portray more developed human beings,” she claims. “Jack [Warner] never understood this, and… he would give me roles that really had no character or quality in them.” When the studio tried to extend her contract due to suspensions incurred for rejecting roles, she brought suit against Warner Bros., citing labor laws. Her victory, in both district and appellate courts, would become known as “the de Havilland decision,” and made her as popular with her newly empowered peers as she was reviled by her suddenly vulnerable employers.

After a nearly three-year hiatus due to de facto blacklisting, de Havilland signed a two-picture contract with Paramount. The first of these, To Each His Own, reunited her with Hold Back the Dawn director Mitchell Leisen and offered the type of role she had craved at Warner Bros.: Jody, a headstrong woman who turns down two marriage proposals and becomes pregnant from a one-night stand for which she never apologizes. When her plan to circumvent small-town gossip by “adopting” her own son is foiled, she implants herself in the child’s life as “Aunt Jody” while he’s raised by one of her hapless ex-suitors and his wife. Meanwhile she takes over the sham corporation of her other hapless ex-suitor (a bootlegger), and transforms it into a legitimate and thriving cosmetics factory whose output further swells when war dictates its conversion into a munitions plant.

To Each His Own is more than a paean to self-sacrificing motherhood in the Stella Dallas vein, despite the recurrence of characters coolly informing Jody that she couldn’t imagine what it’s like to experience something she has indeed weathered in silence—and often these moments prompt flashbacks. But what’s most striking about the film today is how stealthily it embeds a critique of Small Town USA into a product (a high-gloss, Code-sanctioned Hollywood film) designed to extol the values of tight-knit parochial communities. “You sinned and you’ll pay for it all the rest of your life,” a compassionate nurse observes of Jody’s harebrained plot to have the child deposited on the porch of a neighbor, in hopes that she might assume his care without the townsfolk suspecting his true parentage. (The nurse further asserts that she’s glad she’s from the Bronx where people mind their own business—a rejoinder to the Code’s party line, that provincial concern is superior to municipal apathy.)

To Each His Own

Later, Jody’s own father—a forgiving and broadminded man—urges her to surrender custody, declaring “If the people of this town so much as suspect he’s yours, that child’s life won’t be worth living.” Though the comment is woven seamlessly into an extended dialogue scene, this is among the most jarring moments of 1940s cinema: most of our warm feelings for tiny suburban hamlets—especially for those of us who’ve never belonged to one—derive from Golden Age movies that look and sound exactly like this. Yet now our heroine is being told by a man of proven wisdom that their ostensibly idyllic town will persecute her blameless child without empathy or remorse. Nothing that occurs later contradicts this claim—certainly not the callous response of the adoptive mother on learning the truth behind Jody’s largesse. No one we meet in her hometown reveals any ambitions beyond preserving the status quo, and nothing good happens to her until she moves to New York and later London. It takes the intervention of a character out of Dickens—a lonely, powerful English millionaire (marvelous Roland Culver)—to effectuate the film’s happy-but-not-that-happy ending.

De Havilland’s own portrayal is imbued with as much layering and ambiguity as the enfolding tale. Jody ages a quarter-century on screen, and the star accomplishes this feat incrementally, not just with the customary aid of makeup and hairstyling, nor via carryover traits like talking to herself—which Jody does in youth and maturity—but through subtle and consistent changes in her vocal register (conspicuous when we flash back from the Second World War to the First; less so when we return to the narrative origin, having witnessed her progress in small strokes). A largely self-taught actress who bypassed formal training but read Stanislavsky for her own edification, she opted to wear a different perfume for each of the story’s four phases, believing it would help demarcate her character’s growth. If that sounds like a flourish indicative of pretentious self-declared thespians, the proof is in the proverbial pudding: de Havilland limns an utterly convincing transformation, comparable in many ways to that of Fontaine’s career zenith, Letter from an Unknown Woman (and likewise charged with authentic devotion to a man who barely knows she exists). For To Each His Own, de Havilland joined her sister at the Oscar podium, making them the only siblings in history to earn leading-actor statuettes.

She doubled down (Oscar-wise and otherwise) with The Heiress, adapted from Henry James’s novel Washington Square and directed by William Wyler. Her hair parted in the center and braided into a coil that cries out “spinster,” de Havilland plays Catherine Sloper, “an entirely mediocre and defenseless creature with not a shred of poise,” as her father, Austin (Ralph Richardson), describes her with cruel condescension that would send Scarlett O’Hara racing to her defense. The only child of a wealthy upper crust physician in mid-19th-century New York, Catherine is so inhibited by her social surroundings—and comparisons to her charismatic late mother—that she restricts herself to embroidery and Austin’s care. As Jody was pursued by all the men in town, Catherine is valued only monetarily. With stricken glances and halting movements more than words, de Havilland conveys the awkward air of one who satisfies everyone’s expectations of disappointment, and knows painfully well that she does so.

The Heiress

When the charming, impecunious Morris Townsend (Montgomery Clift) beguiles Catherine at a party and begins aggressively courting her, Austin concludes he’s a fortune hunter and, in the stated interest of protecting his daughter, resolves to expose him or thwart the marriage through disinheritance. Thus form the two interconnecting threads: Catherine’s evolving autonomy which warps into malice (“I have been taught by masters”), and the mystery of Morris’s motives. Clift brings enough shading to the role that we remain off-balance, his earnest delivery clashing with his obsequious sentiments—in a testament to the actor’s skill, we tend to see Morris through the biased perspective of whoever observes him. Richardson, a year after his warmhearted turn in The Fallen Idol, uses his resonant, multifaceted voice and classical bearing to etch one of cinema’s decisive parental fiends, yet he, too, allows for the prospect that his motives are just.

Caught between the pair, de Havilland does the hardest thing a high-powered performer can do: she recedes into her surroundings. No faux-wallflower turn this, de Havilland stifles all her innate magnetism, and as Clift and Richardson cross swords she exhibits a believably neutral charge. Neither does she blossom and become more serene as she falls deeper in love, a la Bette Davis in Now, Voyager. If anything, Catherine becomes more self-doubting and reticent, more inclined toward nervous gesturing and fumbling for words. She spends so much of the film insulted and mortified that hers is the polar opposite of a star turn. Like To Each His Own, it is a cumulative portrayal, delineating how past affronts crystallize her resolve, but where suffering all but sanctified Jody, it perverts Catherine into a pitiless monster protected by class and wealth—in other words, into Austin. Standing ramrod-stiff and speaking with a severity that’s truly frightening, her countenance frozen in a mask of pinched endurance resembling a royal portrait, de Havilland eclipses all traces of Melanie, Marian, and midsummer nights.

Since the mid-’50s, the star has made her home in Paris, serving as the first female president of the Cannes jury in 1965. Last year, at 99, she received the Oldie of the Year award from the anti-ageist Oldie magazine—an honor which delighted her, as she claimed it signifies that she still has “sufficient snap in [her] celery.” Mealy-mouth ninny, indeed? Fiddle dee dee.

All of Olivia de Havilland’s films air this month on Turner Classic Movies, including To Each His Own and The Heiress, both on July 15.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.