Make It Real: The Big Short, A Documentary Feature

The Big Short

In 1951, a filmmaker with a background in mainstream comedies directed a serious, timely movie about a subject vital to audiences of its day, which was adapted from a best-selling book and featured actors playing real-life figures. It was considered a work of nonfiction and nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary.

In 2015, a filmmaker with a background in mainstream comedies directed a serious, timely movie about a subject vital to audiences of its day, which was adapted from a best-selling book and featured actors playing real-life figures. It has been considered a work of fiction and nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture.

The first movie is I Was a Communist for the FBI, directed by Gordon Douglas, previously famous for his work with Hal Roach on the Our Gang and Laurel & Hardy films, among others. The second movie is The Big Short, adapted from the nonfiction book by Michael Lewis about the lone wolves who predicted and successfully bet on the subprime mortgage collapse, and directed by Adam McKay, previously famous for his work on the Anchorman films, and his collaborations with Will Ferrell.

I Was a Communist for the FBI

As with other documentary-categorized films from the era, such as With These Hands (50), Daybreak in Udi (49), and Albert Schweitzer (57)—the latter two Oscar winners—Douglas used artificial means to tell a purportedly factual story. Either through urgency of message or anxiety over truthfulness—likely it was both—the just-the-facts assertion of author Matt Cvetic’s autobiographical account of his infiltration into American Communist circles carried the day in how the film was presented and received. The assertion was that this really happened and really happened this way, and so the film had to be considered a documentary in order for that realness to be sold (and unquestioned). With McKay’s film, there’s ample urgency but no anxiety over truth. It flaunts not its factualness but rather its artifice. It’s consistently honest about its artifice in order to emphasize the facts that underlie it. In other words, it’s truthful about its fictions, and confident in its facts. Not only could The Big Short have been considered a documentary in 1951—and a better, more responsible one than the hysterical, propagandistic I Was a Communist for the FBI—it could also be considered one today.

Yes, it’s a matter of semantics, but also of the lens we choose to look through. The Big Short doesn’t ask to be considered a documentary, but it also doesn’t employ the same lens through which we look at most “based on a true story” or “based on true events” fictionalizations. From the very beginning, through Ryan Gosling’s narration as investment banker Jared Vennett, McKay torpedoes suspension of disbelief. We’re never asked to buy fully into McKay’s dramatization of the world financial crisis. Instead we’re asked to hold his dramatizations at a remove, to constantly remember that these are actors playing parts, that the way these scenes play out on screen is not exactly what happened. Voiceover asides let us know that certain exchanges didn’t happen in the locations depicted in the film, that certain scenes have been tarted up for dramatic effect.

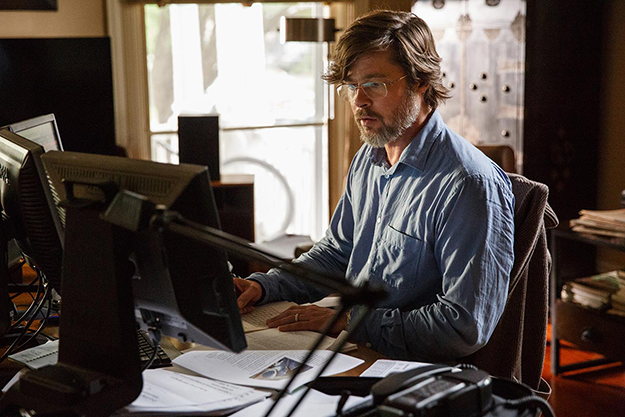

It’s a ploy that fosters skepticism from the audience, but also engagement with each choice and what it conveys. You’re invited to note that you’re watching Brad Pitt play a part, that Christian Bale is working really hard to meticulously impersonate someone you’ve never met before, that Steve Carell is doing a voice and wearing hair that are not his own, that Marisa Tomei is around merely to humanize the morally crucial Carell, that Ryan Gosling is tearing off pieces of dialogue, masticating them around in his mouth, and following every mannered utterance with an invisible fist pump.

The Big Short

If you’re being asked to suspend disbelief, any of these affectations could sink the movie like a stone. But instead McKay is accenting these affectations, fomenting our skepticism, underscoring that this is a big Hollywood show. The film stops cold on three separate occasions for cutaways in which celebrities (Margot Robbie, Anthony Bourdain, Selena Gomez) lecture on the complex workings of various banking-related matters. These aren’t just cheeky interludes in an otherwise straightforward narrative, they’re ruptures that help define the point of view of the entire enterprise. They’re dramatizations within larger dramatizations, and one is no more believable, or asks to be more believable, than the other.

Good documentaries invite us to question the methods and subjectivities of their creators, asserting that we can get closer to truths by accepting (and incorporating) rather than denying human interventions. Less subtle but no less critical-minded, McKay doesn’t just invite such questioning—he does it for us via Gosling’s built-in, piss-take commentary, as well as via pull-back-the-curtain narrative interventions. But such skepticism isn’t fostered in order for us to question the underlying facts—rather it’s used to help us see them more clearly. Facts aren’t employed to spin an entertaining narrative—even if the narrative is often very entertaining—but instead an entertaining narrative is employed to drive us to the facts.

It’s this conviction about the horrible truth of what happened, and the need for us to understand how and why it happened, that drives The Big Short. Say this or that performance is over the top. Say this or that scene doesn’t work. It’s all seemingly secondary to the fact that the movie just might help you better understand the way banks and governments and the corrupt world financial system work. Most documentaries are more committed to their own artifice or arc than The Big Short, which behaves closer to an essay film, or even an instructional film in the negative. Its performances aren’t quite reenactments, but they’re all bracketed off from the actual. They’re attempts not to fool us into believing in them, but to help us to better understand the real scenarios the acted out scenes represent. You can get caught up in the movie, and even experience the escapism that Hollywood movies excel at offering. But that experience is defined by and couched within a nonfictional account. It’s a nonfictional adaptation of a nonfictional text, using fictionalized scenes and performances to enliven text into spectacle, and select readers into mass viewers.

The Big Short

If The Big Short is some kind of documentary—even if only of its own efforts at responsible adaptation and mass communication—where does the line reside between fiction and nonfiction? I don’t really know, and don’t necessarily care, beyond asserting that most attempts at distinguishing one from the other don’t come from thought or precision but from defensiveness or opportunism. Narrative films that boast that they’re based on a true story often want to siphon the gravity and import from nonfiction while maintaining the creative license of fiction. Which is fine, save for the vampirism of the enterprise, stealing from each without offering much to either in return. Documentaries often do something similar, except instead of using fictionalizations as a shield, they pretend such fictionalizations aren’t present at all, that dramatic devices aren’t subjective choices but the natural and necessary methods of storytelling.

What distinguishes The Big Short, and makes it worthy of consideration along these blurred lines, is how deeply it worries about these matters. There’s nothing seamless about its combining fact with fiction, information and entertainment—in fact it’s often supremely awkward. But there’s honesty and ethical sincerity emerging from those seams, which ultimately makes the film more trustworthy than entitled assertions about artistic license or reportorial privilege.

I’m less interested in what McKay’s film does or doesn’t do well than in its scrambling and hustling to find a suitable, mutable form for all that it means to say. Bring us more scripted, acted, and deliberately shot films that call themselves documentaries, and bring us more docu-fictional experiments like The Big Short that pitch themselves to the mainstream as popcorn entertainments. Sometimes working beyond categorization is actually working toward legibility and urgency.

Eric Hynes is a freelance journalist and critic, and associate film curator at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York.