Deep Focus: The Big Short

The Mark Twain quote that kicks off The Big Short, a bold and upsetting tragicomedy about the American economy, could serve as the epigraph to The Collected Works of Adam McKay: “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

As the director and co-writer of brash, hilarious Will Ferrell epics like Talladega Nights and Anchorman, Adam McKay has functioned like a cross between a village idiot and a town crier, lampooning all-American masculine aggression by drilling down into the belly of the beast. (And oh, how Ferrell likes to show his belly in these movies, parading his characters’ beer flab as if it’s a set of six-pack abs.) In Talladega Nights, Ferrell’s NASCAR champ, Ricky Bobby, says he believes in “little baby Jesus,” but he’s devoted most of all to speed and being Number One, because, as his daddy taught him: “If you ain’t first, you’re last.” In the Anchorman movies, Ferrell’s San Diego newscaster Ron Burgundy, an old-school male chauvinist, is riotous when he’s faking authority (calling “Diversity” the name of a Civil War ship), but he’s even more riotous when he thinks he’s telling obvious truths, like women having “a brain a third the size of us. It’s science.”

In McKay’s simultaneously entertaining and nerve-jangling The Big Short, co-written with Charles Randolph from Michael Lewis’s 2010 nonfiction best-seller about corruption and cluelessness in American high finance, the town crier in him takes the helm, proclaiming, with a twisted grin: “All is not well.” But this agreeably messy, multifaceted movie is also full of village—make that global—idiots, as well as a handful of wise guys who are genuinely wise. The most faithful adaptation of a Lewis book to date (the others are Moneyball and The Blind Side), it demonstrates that the U.S. could have avoided the economic meltdown of 2008 if investment raters and bankers and other financial pros had foresworn short-term profits and clamped down on bad loans and chicanery. They needed to react to mounting default and fraud rates, and to the escalating disconnect between flat-lining average income and skyrocketing real estate prices. They didn’t—and Wall Street came tumbling down.

The Big Short functions as a real-life Kafka farce. The only players who see what’s happening are regarded as misfits, because, as conventional wisdom had it, “who doesn’t pay their mortgage?” and “when has an investment bank failed?” It’s the most difficult kind of real-life movie to pull off—one based on the recent past—as well as a cautionary tale about Americans’ eagerness to believe in concepts too good to be true, like ever-expanding home ownership and increasingly easy-to-get mortgages. McKay may stumble, but he does pull it off. To get across his message he uses every tool in a reality-slapstick arsenal, including peppy Sixties-style montages of media distractions and hedonistic excesses.

One unreliable character—a natty and narcissistic bond trader, Jared Vennett, played by the witty, ultra-assured Ryan Gosling—proves himself to be a surprisingly reliable narrator. Celebrities like Margot Robbie, Anthony Bourdain, and Selena Gomez also address the audience directly, as themselves, delivering primers on abstruse investments. Best of all, the core of renegades who see Defaultageddon coming hang on to their convictions as fiercely as Ron Burgundy’s posse do in the Anchorman movies. Unlike those bozos, these guys can tell truth from fantasy.

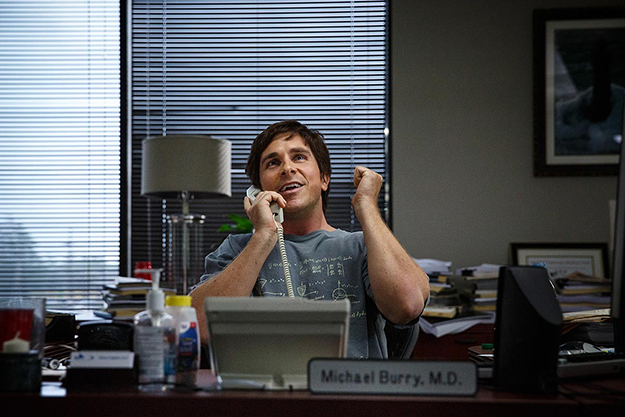

First up is Dr. Mike Burry (Christian Bale), a one-eyed Stanford-educated neurologist turned hedge-fund manager, with an Asperger’s-like affect and hyper-focus that he maintains by drumming to head-banging rock music. His patience for and skill at reading numbers convinces him that the housing market will collapse along with the financial institutions that have milked it of any concrete worth. (Burry is the most pivotal character portrayed under his real name.) Vennett gets wind of Burry’s analysis and believes it. He appreciates the brilliance behind Burry’s creation of “credit default swaps” for subprime mortgage bonds, which empower investors to wager on the impending collapse of overrated real-estate securities. He seizes the chance to get in on the maiden ride of a money train. And Gosling’s Vennett, who narrates directly to the camera, is the perfect anchor for this movie. His version of Vennett is so straightforward and clear about his own status-crazy haughtiness and rampaging self-interest that the actor almost makes the self-loving bond trader likable.

Vennett lures in Mark Baum (Steve Carell), a hedge-fund manager who detests dishonesty and sees betting against the economy as a way to punish fraudulent, arrogant banks and money managers. Baum is the one major player who carries a moral sense from the start, although Burry develops one. So do Charlie Geller (John Magaro) and Jamie Shipley (Finn Wittrock), the bubbly, innocent founders of a “garage band hedge fund” who simply want to get super-rich super-quick. Brad Pitt gives these boys the benefit of his sardonic gravitas as a retired Wall Street titan who enables them to make huge deals but who also mentors them in the wages of greed along the way. He tells them that for every additional percentage point of unemployment, 40,000 people will die.

Accustomed to conventional adaptations, audiences wait for these characters to intersect, especially when nearly all land in Las Vegas to attend an appalling convention of financial schlockmeisters. Actually, they stay in their separate spheres. McKay lacks the storytelling skill to wring delight from upending expectations about who doesn’t interact with whom. But that’s a minor narrative flaw. What unites McKay’s protagonists to his own plain-speaking strengths as a filmmaker is their ability to see exactly what’s in front of them: evidence that the entire U.S. banking system is so debased and riddled with bad judgment that it’s hard to distinguish between stupidity and criminality. From the moment Burry decides, in 2003, that (in Lewis’s paraphrase) “the real estate bubble was being driven ever higher by the irrational behavior of mortgage lenders who were extending easy credit” to the moment he shuts down his fund in 2008, having learned “this business kills the part of life that is essential, the part that has nothing to do with business,” the movie hurtles along like two parallel locomotives. On the one hand, you root for men of integrity like Burry and Baum to pocket the millions they earn for seeing through a venal industry. On the other, you want them and the two whiz kids to do more than Pitt’s character did—not just wash their hands of the Wall Street mess but also warn their fellow Americans of its economic threat.

McKay uses cinematographer Barry Aykroyd, a master at capturing eloquent details in real, lived-in places, to evoke the pathetic glitziness of Vegas, the incongruous sadness of a deluxe ghost suburb in Florida, and the spirit-killing emptiness of abandoned Wall Street trading pits and office suites. Under McKay’s guidance, Aykroyd isn’t the sharp-shooter he was for Kathryn Bigelow in The Hurt Locker or Paul Greengrass in Captain Phillips. Sometimes he moves his camera too close to Bale and Carell at their quirkiest, making their performances seem caricatured.

Luckily, both performers can withstand this scrutiny. Bale, in one of his most extraordinary transformations, is alternately funny, tough, and oddly moving. He conveys Burry’s rueful recognition of his own social ineptitude, his fraying grin-and-bear-it attitude toward slick operators who condescend to him, and his righteous determination to stand by his analysis. Carell manages a more difficult feat: in the opposite of a “slow burn,” he maintains a high flame of outrage for two hours with occasional breaks for volcanic eruptions. He’s believable as the charismatic center of his joshing, goading, super-intelligent hedge-fund team: Jeremy Strong’s straight-shooting, bullet-eyed Vinny Daniel, Hamish Linklater’s bemused Porter Collins, and Rafe Spall’s oddly convivial Danny Moses. There’s unexpected depth to Carell’s performance. Baum acts differently when he’s leveling with his wife, the always appealing, always underused Marisa Tomei. Only with her can he strip himself bare. McKay doesn’t gracefully integrate Baum’s personal agony into the overall story. (The script gives him a melodramatic family tragedy that differs from his real-life counterpart’s loss of a child.) But Carell successfully imbues the film with a moral consciousness, and Baum is resolute in his concern for the exploitation of the middle and working classes. Carell makes his guilty conscience palpable.

The movie is refreshingly unsentimental but not heartless. At times, everyone outside this small band of truth-tellers can appear to be soulless big shots or cheerful lemmings following shady experts over a cliff. But the movie showers uncomplicated sympathy on innocent bystanders, like a husband and father who doesn’t realize that his landlord is a crook, or the stripper who keeps buying new properties by refinancing her previous ones, since she believes that real-estate prices will always go up.

Even when McKay focuses like a laser on arrogant losers, he does it in smart, modulated ways. His satiric mastery of bro culture informs the smugness of this film’s vast cast of supporting doofuses (or is that doofi?). McKay’s understanding of all the ways humans can be idiots brings humorous shock, then poignancy, to the depiction of a couple of party-guy mortgage brokers who brag about signing deals with home buyers who are unemployed and asset-free. (Later, they look stunned, as if they don’t know what hit them.)

You cheer for Baum and Burry as they shame the rigged financial structure that booby-trapped investments and supported nests of economic vipers. But in this movie, nobody gets the last laugh. The Big Short ends with a lament that no big culprits in the crisis went to jail and a warning that a new credit bubble is starting. It’s as if McKay is following you out of the theater and whispering in your ear: “Don’t let the real laugh be on you.”