Interview: Nelson Carlo de Los Santos Arias

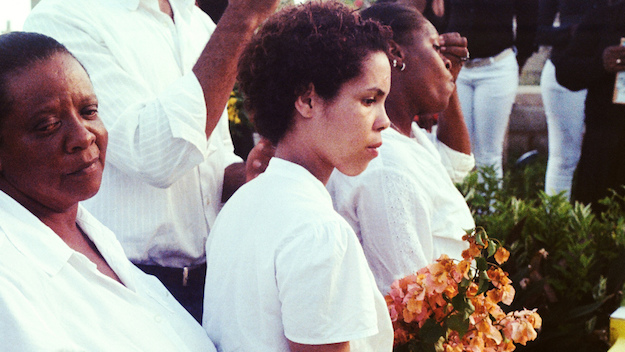

At this year’s Locarno International Film Festival, the winner for best film in the Signs of Life section was Cocote, a convulsive drama of vengeance and grief by Nelson Carlo de Los Santos Arias. Set in the CalArts-schooled director’s home country of the Dominican Republic, it’s the story of a gardener, Alberto (Vicente Santos), as he returns home after his father’s death at the hands of a police officer. Bringing a rare energy to camerawork and color, de Los Santos Arias pulls out all the stops in rendering not just the cruelty of Alberto and his family’s experience but also their own vibrant modes of expression, in daily life and the beyond, as in its immersive depiction of syncretic funeral rituals. Film Comment took a moment to speak with the filmmaker in Locarno just before a public screening of Cocote, which, as he explains, feels like a sledgehammer to the anthropological spaces often opened up by long-take gazes. (Cocote screens April 3 and 4 in New Directors/New Films. It opens August 3 at IFC Center.)

In your director’s statement, you talk about a childhood memory of an ominous conversation: your great-aunt talking to someone who worked for her who may have killed someone. Does Cocote come out of that experience?

There are a lot of violent stories in the Dominican Republic. It was not actually because of the violence in the story… What happened was, I went to a very proper film school in Buenos Aires—one that was not necessarily very interested in this type of film. And then I went to the Edinburgh College of Art and CalArts. And I had this story about this guy. I wrote a little treatment, but there was a moment when I didn’t want to do Cocote because it was not representative of myself at that time, or what interested me in cinema. But then I found something that I clicked with in the story. I started investigating the idea of being on the periphery, and this relationship between the visible and the invisible and what happens when this invisibility becomes visible.

I was thinking about this world of the periphery, these people that come and go. The classes, the people, that rule the society are few in numbers, but they are the majority in terms of power and control. I come from an educated, middle-class family in Santo Domingo and, in relation to the Dominican Republic, I am a privileged person. Coming from a lefty family, I was always in this in-between world because of my parents and because I went to good schools. So I started to have this problem with people, that they don’t know what a day’s work is and what the relationship with work is—in the way that a housemaid works, in the way of jobs that we have in the Dominican Republic. And not just the Dominican Republic, the rest of Latin America. For me, that’s when Cocote became interesting.

Can you explain the title?

It means “neck,” and that’s only in the Dominican Republic. The Spanish of the Dominican Republic is very, very different. Everywhere in Spanish they say cojote, but in the Dominican, we say cocote. Cocote is the neck of an animal, not a human being, and it has a lot of meaning. When you say cocote, it implies violence. It’s the idea of a neck of a chicken that you are going to break. You don’t say cocote if you are speaking nicely of someone. It’s one of those words that has this invisible meaning. Very visceral.

How did you find and cast the leads in Cocote?

It was a huge process—I saw so many people, you cannot even imagine. I had an open call in different communities in the country. And you go to these places and there are 600 people and they don’t even understand what casting is. I spent a lot of time explaining. Once I found my people, I rehearsed a lot. A lot, a lot, a lot. The professional actors especially came from theater, and there’s no big tradition of acting, in general, in the Dominican Republic.

Why do you think that is?

What makes something good from a country, like good actors or good sports? The institutions. There’s no support. We have a lot of baseball players there because of these American baseball camps that take kids. There are a lot of very talented people [in acting], but in the Dominican Republic, people are very performative. Are you from New York? You know—I mean, why do I need actors? They’re amazing! Everybody’s an actor. So I was trying to take this very old idea of theater out of their minds, and then I found each of them as a person, and they were amazing. But I needed to get rid of that idea of what drama is. They would come to me like, “But when is the twist?” and I’d say, “There’s no twist.” And I make them live with that.

Vicente [Santos] is an amazing professional, so disciplined.

He hardly needs to say anything, because of his presence.

And he started as a dancer. He’s actually a dancer.

Thinking about playing roles in another sense… was it challenging to shoot the religious rituals depicted in the film? How do you go about rendering something spiritual and intimate?

I’ve known this community for a long time and I’ve been in so many of the rituals. To be honest, I didn’t even think that it was difficult. They’re there. I wasn’t trying to make a narrative film. The difficulty actually was because I brought people that worked in commercial and narrative films, and for them, those scenes were very difficult. So most of the time, my solution was to take everything and everybody out, and just stay by myself with the camera. Because it comes from me, I know how to make it, to shoot it, and I studied cinematography in film school. So basically the whole ritual is just me shooting. It was the only way, because they were not getting it—it was too overwhelming for the crew. When people see cinema as different departments, it’s amazing how they say, “I don’t know how to decide this. What would the director say?”

I changed the whole production process to shoot the rituals. The ritual goes from 9 to 5—they do some Hail Mary’s, some Holy Father’s, then they have five mysteries. I know this very well, so I decided to do half of a mystery, so every day, I can get that totality: we do the rituals from 3 to 6, with no cut. So it becomes documentary. I said to the sound guy, “Okay, you put a lot of microphones in the whole house and we’re gonna start.” So over four days, I have 12 hours of this.

It feels like we’re living it.

People were just crying for real, crying because of their own deaths, because these are prayers and chants that are sung for anyone who died, so everybody has their own chant. So it was a re-creation, but I don’t have to make them act, because two months ago, someone died. There’s one every month in a community.

It’s beautiful how the rituals allow people to express their grief and get it out.

And this is not just this popular class, this is the Dominican Republic. It doesn’t matter what social class. The people might be lighter-skinned, or there’s gonna be a Catholic priest from wherever, but in that cemetery, people are just gonna go crazy. You could be blonde with blue eyes, it doesn’t matter, if you’re Dominican—because this is how we are. People go pretty insane. Maybe I’m gonna do that for my mom or my dad!

At the end of the movie, there’s another kind of release: an act of vengeance. You film a sequence with a remarkable 360-degree camera movement, a continuous shot. What was the thinking behind that?

It’s my investigation, linguistically, of my Spanish—the Caribbean is where all this craziness started. Accumulation, repetition, and singularity can form morality linguistically. It’s the only way that we can share something. With the construction of capitalism and imperialism of the English empire, you could see in the colonies how they destroyed the English language. The Jamaicans, for example, and in the Dutch islands or in the French islands, they went even more radical and created their own Creole. In Aruba, which is a Dutch colony, they talk Papiamento, which is a crazy mix. Then you got the Spanish Caribbean, which is Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic. We created a Creole but we go very far from the idea of a good way of speaking Spanish—and it’s going to get destroyed. Because the idea of speaking good gets closer to the idea of being white or European, you know?

The idea of proper Spanish.

Yeah, it’s proper. For me, it’s so amazing when you see something that is implicit that is not necessarily intellectualized—that is the real resistance of a Caribbean country. It’s a clear fuck you to the language of the colonizer! So this is why I’m going to create images in terms of camera movement, or in the way I’m going to go through a scene to another scene. I like the idea that the film is a circle because we speak in circles, so maybe if you spend a lot of time with me, you will see that I also think in circles, you know? The 360 is not only because it’s beautiful, it’s very cinematic, but it’s also very interesting because you are in a constant problem—it’s making visible and invisible all the elements of that scene, in and out of frame. Putting the action inside and outside at all times is the way my mind works.

It’s sacrilege in narrative films to lose the point of view of your main character, so what’s interesting for me is the idea of losing that point of view. So I break the point of view of Alberto as a metaphor of breaking his right as a citizen, because of his social condition. In the moment that he goes to this garden again, he’s just an element of the garden. He loses—he always loses.

What are you working on next?

I was gonna take a break because I’ve been doing films every year and I’m very tired. But I just went to Colombia, and there’s this story of a hippopotamus that I think is amazing. I would like to make a film where the main character is a hippopotamus. But maybe it’s gonna be a very boring film.

I would watch that.

But what can I do? The guy is definitely not going to talk, you know? But I don’t like slow films. I don’t like these long, wide-shot films. You know, James Benning…

Did you take a class with him at CalArts?

Oh yeah! And he’s a friend of mine, but I told him, “I’m not making films like that. I hate long takes.” And he laughed. So I don’t know, I mean, you have to follow a hippopotamus. You know what happens when two hippopotamuses fight?