Interview: Nina Menkes

All images from Queen of Diamonds (Nina Menkes, 1991)

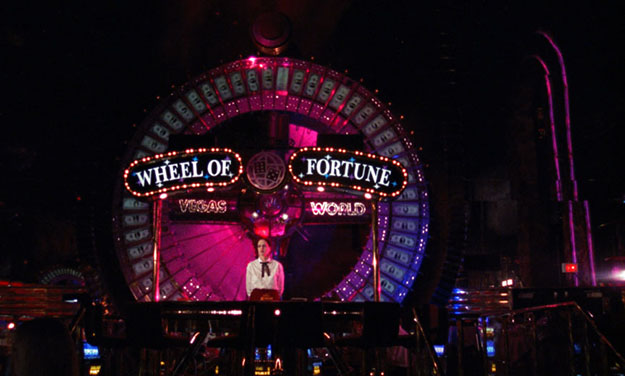

Of all the female filmmakers to reemerge in recent years, Nina Menkes is perhaps the ripest for rediscovery. Her small but crucial body of films—five features, two shorts, and one co-directed documentary, produced intermittently over the course of three decades—remain startlingly fresh and near peerless in their intense focus on violence, power dynamics, and the inner workings of the female psyche. Recently restored by the Academy Film Archive and the Film Foundation, Menkes’s 1991 feature Queen of Diamonds remains perhaps the best entry point into her slippery yet strikingly holistic filmography. Starring her sister and frequent lead Tinka Menkes as Firdaus, an adrift and alienated blackjack dealer in Las Vegas, the film proceeds in deceptively complex, elliptical fashion befitting its disenchanted protagonist. In lengthy, static compositions that vibrate with nascent tension, Firdaus solemnly navigates the less glamorous corners of the city. Her existence is one of numbing routine and ambient anxieties: endless nights on the casino floor, afternoons spent tending to an ailing older man in a motel room, and the incessant sounds of domestic violence emanating from a neighbor’s apartment. (Her own husband, meanwhile, is mysteriously absent.) Interspersing these recurring story threads with dreamlike passages that play like vivid projections of Firdaus’s fraught psychology, Menkes constructs a temporal slipstream of images and emotion that, almost 30 years on, has lost none of its beauty or essential mystery.

Prior to the April 26 release of a new restoration of Queen of Diamonds at BAM in New York, Menkes and I spoke about the film’s lingering and unexpected influence, her solitary writing process, working outside patriarchal cinematic norms, her six collaborations with Tinka, and her touring audiovisual talk “Sex and Power: The Visual Language of Oppression.”

A couple of years ago you mentioned to me that many of your films were in a great need of restoration. Among other things, watching the restored version of Queen of Diamonds really underlined how important its color is, especially the various shades of blue. In comparison to some of your other films, where did Queen of Diamonds stand as far as deterioration and/or damage before the restoration work?

In 2017, I was invited to screen Queen of Diamonds in Berlin, on the occasion of the 50th-anniversary celebration of the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB). As I found out during the introduction, and much to my complete amazement, this movie has been very influential for filmmakers loosely known as the Berlin School, such as Nicolas Wackerbarth and Angela Schanelec. I say complete amazement because I actually had felt that my films, much like the 35mm print that we screened, had sort of faded out from cinematic consciousness. The colors lacked the brilliant intensity of the original. The optical soundtrack, being scratched from multiple screenings, was less than great, and the overall sharpness was diminished.

This is true of all my older film prints, but both Queen of Diamonds and The Bloody Child [1996], especially, need pristine conditions to be fully appreciated. This is because both these works use many long shots—long both in duration and in terms of shot from far away—so in order to experience the details of the image and Tinka’s essential, subtle performance, it’s important to have the restored version. The soundtracks are also both subtle and layered, and on the older prints sound gets fuzzy, with loss of significant detail.

I had never made the Berlin School connection, but I can certainly see where your influence might come into play, particularly in many of those filmmakers’ elliptical way with narrative. I know you watch a lot of new movies: do you see much of yourself in contemporary cinema? A few critics compared Twin Peaks: The Return to your work, and I think Queen of Diamonds is an apt corollary, and not simply because of the shared Vegas setting but in the way you shoot landscapes and for the most part set your story on the outskirts of the city.

I guess I see my films as existing largely on the outskirts, in an existential sense, of contemporary cinema. I’m complimented by a comparison to Twin Peaks: The Return, especially Episode 8; this is a violent netherworld, cinematically rich and wild, functioning on unconscious dream logic, and I think my films are like that too—though mine are more minimalist. I love David Lynch’s work in many ways, but his treatment of women is not as experimental as the rest of his work. We still get very traditional depictions of sexualized women with Lynch, and a sympathy, often, with the male-abuser position.

So while my films come from the same interior, oneiric core, they are deeply informed by the experience of being marginal, as a woman: an outsider on multiple levels, not the least in how I experience the elements of time and space cinematically. In contrast to Lynch, the dream zones I enter as a filmmaker are all inevitably politically charged with my perspective of a life lived in resistance to patriarchal norms on pretty much every level: emotionally, spiritually, and cinematically.

My mother’s family, from Berlin, escaped Hitler and resettled in Jerusalem when she was a small child. My father was born in Vienna, and his family was deported and gassed by the Nazis; he was rescued and brought to British Mandate Palestine in 1940. When I had a retrospective in Vienna, very many years later, I was wandering the streets alone, during the days, and totally freaking out without really knowing why. At one of the screenings, I was asked about the excruciating disconnect that is expressed by my female characters; I responded that it was my alienation as a woman in a completely inhospitable male world. The programmer, Wilbirg Brainin-Donnenberg, later asked me if I didn’t think my family’s brutal history with the Nazis had something to do with it. I was taken aback. I had never thought of that. But she was right.

It has now apparently been determined that we carry trauma, intergenerationally, via DNA—it’s literally in our genes. So the combination of a Holocaust personal history and a fiercely feminist consciousness makes my connection to Chantal Akerman’s work very clear. And I love Vagabond, by Agnès Varda. When I first saw it, I related so completely that I felt I could have practically shot that film myself! Mona’s total refusal to collaborate with “the system” spoke to me deeply: she ends up dead in a ditch. I understand this more than words can express.

I love Alice Rohrwacher’s The Wonders—such a fluid sense of time, space, and the way she makes the real world feel a natural part of the imaginary. Connecting the seen to the unseen. I see my work that way, too, although of course her visual style and tone are very different.

Watching the Queen of Diamonds restoration at AFI Fest this past November, I was struck by the fact that it feels very current; it could have been shot last year. But I’m not sure I feel affinity with most contemporary cinema.

In terms of Queen of Diamonds feeling very current, I’m wondering if the film has changed at all for you in the years since you made it? Looking back, was your conception of the film—whether before shooting or in the years following—any different than how you see it now? And do you think other people see it differently now when viewing it for the first time as compared to initial audiences? The film develops themes and approaches time in a deceptively complex and enigmatic way that’s distinct from even your previous feature, Magdalena Viraga [1986]. Where do you see Queen of Diamonds in the context of your career?

My films form a continuum that, among other things, closely track my own interior psychic process, a process embodied for many years in the presence of my sister and actress Tinka. Queen of Diamonds was the fourth film we made together and it expresses a level of alienation that is more extreme than that which appears in Magdalena Viraga. I see this deeper alienation in the almost total lack of close-ups, in the nightmarish 17-minute blackjack-dealing sequence that is, for me, a vision of hell in which the main character is trapped, and in the way that Tinka’s character, Firdaus, is in every scene but at the same time retains the quality of being a background figure.

I named my character Firdaus, an Arabic word for “paradise,” in honor of the heroine in a novel by Nawal El Saadawi, Woman at Point Zero, about an Egyptian prostitute who kills her pimp and refuses to express remorse, even though to do so would have saved her from execution. Firdaus, in Queen of Diamonds, not unlike Ida in Magdalena Viraga, is indeed deeply damaged and disconnected, but she also has an eerie power, perhaps born of her uncompromised inner refusal to worship false gods. Is Firdaus/Tinka the one who causes the palm tree to ignite and burn in the desert, or an upside-down Jesus to appear on the street? Is her rejection of the system enough to bring it down, or at least to cause a fissure?

I think the fact that people now have an increased interest in this film, and that it has a strange quality of freshness—also to me!—even though it was made long ago, testifies to the truth of Tinka/Firdaus’s psychic power, as well as to the fact that the film was made, on my side, intuitively, by focusing inward and without regard for external cinematic norms. I was trying to tune into my own deepest experience about the political/emotional situation the film speaks to, and to then express that cinematically. For example, it felt like a fact and an imperative that the dealing scene had to be one long sequence. This decision actually appeared during editing: five or six distinct dealing scenes, which ended up as one single monster sequence, were originally written as individual, separate events. Even though I was very afraid that most of the audience would walk out during the casino scene, I knew it was right. And I want to acknowledge Tinka for having the idea to cut the film like that.

In fact, I would say that the way my films deal with time is maybe one of the best things about them! Social power dictates not only who gets to earn money and who doesn’t, who is central and who is marginal, but also how we are supposed to perceive space and time. I agree that Queen of Diamonds has a more unusual approach to time than Magdalena Viraga, but our following film, The Bloody Child, is even more radically structured.

I’m not sure how Queen of Diamonds fits into my “career,” per se, because my films never felt like a career to me, but more like a vocation. And while a vocation can sometimes also be a career, it’s first and last a vocation, and if a career happens, that’s a very lucky miracle and an unexpected side effect.

Every one of my films has been created on an insanely low budget, and I’ve never really made any money from my films. For Queen of Diamonds I had around $50,000, and half of that went for 35mm film and processing. We spent hundreds of hours on the phone asking for donations, from a camera package to coffee to a free hotel stay in Vegas. It’s possible that with the restoration of Queen of Diamonds, and if there is a new and wider appreciation for this movie, and for my work as a whole… who knows? I have two feature scripts that I’m dying to shoot; I would love to have a decent budget for the first time in my life.

Can you describe the writing process for Queen of Diamonds? Did you approach the script-writing process at all differently than you had with your previous works? This film especially feels like a series of discreetly organized and structured scenes, so much so that it can probably seem to the casual viewer like they were pared down from longer sequences in the script. It’s also, perhaps coincidentally, your shortest feature. Were the film’s many ellipses something implemented in the edit, or was this all written from the start?

The entire movie was shot without deviation, word for word, from a very precise script. None of the scenes were shortened, although the casino scene, of course, was lengthened, as mentioned earlier. Scenes that might appear like random moments, or perhaps as documentary, such as the elephants swaying at night, or the wedding scene, or even the palm tree burning, were all carefully constructed.

The film was also cut almost exactly as written, except for the massive dealing sequence. There was also one scene that I had written, but eventually cut out: I had a voluptuous naked woman, lying on a sandy beach, covered with little seashells—unclear if she is dead and washed ashore, or if she is some kind of sleeping Sea Goddess. This woman was supposed to appear toward the end, during the wedding scene. But ultimately, those images didn’t feel right.

My method of screenwriting is, I suppose, exactly backwards from the traditional system! What I have always done, over a period of time—and it can be many months, or a year or more—is write down images on 3×5 cards, either things that I actually see in real life or interior images that appear to my mind’s eye: “a burning palm tree,” “suicide in a car outside a casino,” “dealer is working in the casino,” etc. Sometimes images come to me in dreams, like the upside-down Jesus on the cross. I write down those images that have strong energy and demand my attention. So after I have a pile of these cards, I just have a feeling that I have enough at some point, an intuitive sense of closure. Then I start reading all the cards and seeing what narrative thread exists, and I start stringing the images together as a script. So whereas in more standard screenwriting the story comes first, with images added later, my system uses the images to lead me toward unknown narrative or semi-narrative destinations.

Can you talk about your collaboration with Tinka? I find her a fascinating figure, as she’s so central to your first phase of filmmaking—and is such a memorable and striking presence—and yet as far as I can tell she’s never acted in any other movies. I know she’s worked in various capacities on some of your other films—she’s credited with co-editing The Bloody Child, etc.—but how involved in general is she with the creation, or even the writing, of her various characters, and with Firdaus in particular?

Tinka and I made five films together [A Soft Warrior, 1981; The Great Sadness of Zohara,1983; Magdalena Viraga, Queen of Diamonds, and The Bloody Child]. In all of them, her participation was both essential and revolutionary. Tinka didn’t actually co-write anything with me—my scriptwriting process, as I explained earlier, was, and is still today, very quiet and private, but on the films where there was no script at all, such as The Bloody Child, she contributed central ideas in terms of both content and structure. But even on the films that were shot from very precise scripts, like Magdalena Viraga and Queen of Diamonds, Tinka brought a consciousness to the set that permeated the atmosphere with electricity.

It’s hard to exaggerate the impact of having someone—namely, your lead—on set, and knowing/feeling that she has a profound, psychic understanding of what we are doing, both on the micro level of an individual scene and on the macro level of what the whole film is really all about. Especially since what we were doing was not at all traditional, so that making each film felt like a mysterious and potent adventure into the unknown. Tinka always, intuitively, knew more about what was really going on in the movie, on its subterranean levels, than I did. And also, she is brave. She takes things to the edge, in a very subtle but intense way. I could sense this while shooting: it gave me courage and liberated me to do my best work.

In terms of acting, in Queen of Diamonds I had this image in my mind of a woman blackjack dealer who was a drifter, and a loner. But Tinka took that much further, to a transcendental place where the deep wounding of the feminine in our culture intersects with American violence. I don’t know… I can’t really explain it. We had a sort of telepathic understanding so that I didn’t have to do much overt directing outside of staging the scenes. She always took things deeper than I could have ever imagined, and later, in postproduction, her editing insights were unique and radical—and her ideas were never about style, per se; rather, they involved bringing out the core meanings of the film formally, structurally.

Due to a debilitating, life-threatening physical illness with which Tinka is still struggling today, our cinematic collaboration ended after we finished The Bloody Child.

You presented a talk titled “Sex and Power: The Visual Language of Oppression ” at Sundance in 2018, and will be doing so again at BAM on April 27. The talk was initially prompted by the Harvey Weinstein scandal, but you’ve clearly been working through these ideas and how they relate to cinema for decades. Can you describe how these ideas first coalesced into what would become an audiovisual presentation? And in the year-plus that you’ve been giving the talk, has it evolved at all? Are you continuing to add films or examples to the presentation?

I always had an intuitive sense of the political resonance and meaning of shots and narrative structure. In fact, the reason I have to shoot all my own films is that it is really only through the camera lens that I understand and feel my way into my own movies. If I stood to the side and had someone else frame and film my shots, I would feel disconnected and lost.

When I taught filmmaking at USC in the ’90s, Marsha Kinder invited me to co-teach a Critical Studies course with her: “Gender and Film.” I was the production arm of our teaching team, and Marsha provided the theory. That’s where I first read Laura Mulvey and other feminist theorists. It was great, because it gave me a language to speak articulately about things I had always felt. I first gave a version of my talk, publicly, in Berlin in early 2017 when filmmaker Nicolas Wackerbarth asked me to participate in the DFFB celebration mentioned earlier. But ever since Marsha Kinder’s class, I’ve been showing my students variations on my “Sex and Power” talk: a series of clips from A-list directors, exposing how shot design serves to formally disempower women on screen.

The reaction is always shock, depression, and, well, maybe even terror. At least, a great majority of my women students often feel that way. Gendered shot design: angles, lighting, framing, and camera movement have become so normalized that we are inured to it, and when all that comes to consciousness, it can be rough. So when the Weinstein story broke in The New York Times in October 2017, I decided to write an essay about how the formal language of cinema is an important causal factor in the issues addressed by the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, and might even be called the bedrock of rape culture. Much to my surprise, the article went viral on Facebook and was later named Filmmaker magazine’s most popular article of the year! Suddenly, more people were interested in my talk; this was no longer felt to be the stuff of obscure film theory; rather it was and is clearly about our contemporary, daily lived experience. As women we are marginalized, objectified, and turned into use objects every day, in our lives, and on the screen—and very often in those very same films that win Academy Awards or top prizes at Cannes.

I most recently added a few clips showing how some of the shot design strategies used on women are also used on other marginalized groups, such as trans characters—so yes, the talk is definitely an evolving entity. I’m also happy that “Sex and Power” is now being made into a feature documentary, working title Brainwashed, produced by Tim Disney at Uncommon Productions, and Elisabeth Bentley’s Marginalia Pictures. This will allow the important information I’ve been speaking about for decades to reach a wider audience and maybe even have a real and meaningful impact on working filmmakers, as well as on the wider collective consciousness.

You mentioned two scripts you’re hoping to shoot. Can you tell us a little about those projects and what roadblocks you’ve experienced over the years as far as funding and finding support to produce new work? I can’t help but notice all the grants and funding bodies listed in the credits of your early features. How much more difficult has it been to find funding in the 2000s? A 2012 New York Times article about your work mentions a film called Heatstroke that apparently never came to fruition.

This is a fraught subject! I love filmmaking on every level except the financing part, which is almost always grueling and feels so incredibly difficult. Being a woman director doesn’t make it any easier. I had shot my first feature Magdalena Viraga on weekends while I was a student at UCLA film school. We were stunned and thrilled when the film won a Los Angeles Film Critics Association award for Best Independent/Experimental Film of 1986. The film was also selected for Toronto and included in the Whitney Biennial. In other words, this movie got a lot of attention! But it did not lead to any offers from the moneyed Hollywood crowd. Zero offers, to be precise.

My films have been appreciated since early on by a certain group of film critics and cinephiles, and I’ve received probably almost every form of public support that exists—grants from the NEA, Guggenheim, Rockefeller, Western States Regional Media Arts Fellowships, Creative Capital, and more. But while all these awards are prestigious and deeply appreciated, they aren’t much actual cash money. All my films, made on minuscule budgets that rarely contained even one cent of salary, exist today due to my intense, driven need to make my movies come hell or high water and at any cost, except compromise.

While I watched male colleagues make acclaimed first works and then get significant money for their second, third, and fourth features, this is something that almost never happened—and still rarely happens—to women directors. The fact that I am female is part of it, but the content of my films makes it more intense. For example, Magdalena Viraga is about a prostitute who hates her work. She is angry, alienated, and never takes her clothes off. So, as per my “Sex and Power” talk, I disobeyed the essential cinematic laws of gender, and paid a heavy price for doing so, financially. On the other hand, I have my integrity intact.

Not long after finishing The Bloody Child, I wrote the first draft of Heatstroke, a political thriller about two sisters set in Los Angeles and Cairo. Heatstroke is an Escher-like exploration of psychological trauma, unfolding against the fractured backdrop of the West and the Muslim world. This project was set up, as you mentioned, some years ago, by Chris Hanley at Muse Productions, but there were obstacles with the financing. However, the good news is that Heatstroke just got accepted to a new women’s pitching session at Cannes 2019, “Breaking Through the Lens.” I’ll be flying over to locate and close financing along with my producer Elisabeth Bentley. Bentley will be at the festival in her capacity as the producer of Terrence Malick’s latest film, A Hidden Life, premiering in Competition. I’m sure our combined powers, along with the awareness, finally, of how women have been systematically excluded from the canon, will mean that Heatstroke can now come into being, at long last.

The second feature script I want to shoot is Minotaur Rex, produced in part by Gwen Wynne and the EOS World Fund. Minotaur Rex is a drama-thriller based on the original Greek myth of the Minotaur but set in contemporary Jerusalem. The story works both as an allegory for the political situation about the racist oppression of the Palestinian people but is also about the inner journey of one man who is willing to face and wrestle with his own shadow sides. The journey within to face the self is something that all my films are ultimately about, and it is the aspect of life that I am, personally, most committed to above all else.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival.