Interview: Mike De Leon on Philippine Cinema

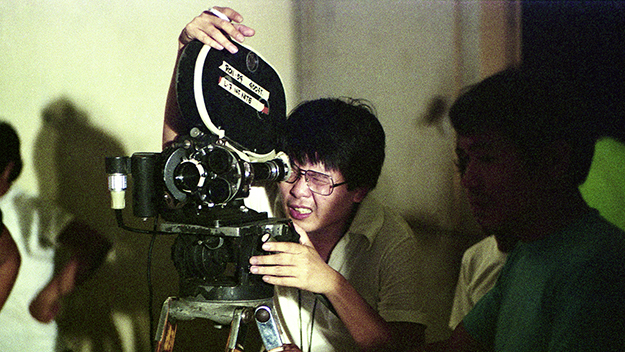

Itim: isang eksplorasyon sa pelikula [Itim: An Exploration in Cinema] (Clodualdo “Doy” del Mundo Jr., 1976). Courtesy Mike De Leon

An eminent filmmaker of the so-called Second Golden Age of Philippine cinema, Mike De Leon was a peer of Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal. But where Brocka made what some regard as “poverty porn,” drawing attention from the European festival circuit with Manila in the Claws of Light (1975), and Bernal celebrated the social lives of his own urban middle class with films like City After Dark (1980), De Leon both embraced and scathingly critiqued the upper-class, film-literate world from which he came—a powerful dynasty of movie producers.

Founded in 1938 by Narcisa “Doña Sisang” De Leon (Mike’s grandmother), the family’s production company, LVN Pictures, became one of the “big four” studios in the Philippines between the 1940s and 1960s. Under her supervision, the studio produced about 25 films a year during what is considered the First Golden Age of Philippine Cinema. Sisang favored popular costume epics and lavish musicals inspired by Philippine metrical romances, the awit and corrido, while her son (Mike’s father), Manuel “Manny” De Leon, preferred social-realist dramas and prestige pictures that could win awards and measure up against the venerated cinema of East Asia.

De Leon’s own eclectic films fall somewhere in between: they neither alienate the public with art-house pretension nor patronize them with formulaic narratives. His debut feature, 1976’s Itim (The Rites of May), a gothic horror about spiritual possession, eludes easy payoffs and climactic scares. 1980’s Kakabakaba ka ba? (Will Your Heart Beat Faster?), an absurdist comedy about a pair of lovers on the run with an opium-laced cassette tape, is filled with madcap gaps of logic that bring its roller-coaster storyline to the brink of collapse. Batch ’81 (1982) strikes out at the fascist Marcos regime of the 1970s through the metaphor of a hyper-violent college fraternity initiation, while Sister Stella L. (1984) is no-frills agitprop, the story of a nun who becomes a key figure in a cooking-oil factory strike. Aliwan Paradise, De Leon’s contribution to the Japanese-produced omnibus Southern Winds (1992), imagines a near-future Philippines where a “Ministry of Entertainment” conducts job interviews like judges in a game show.

In 2020, I heard that De Leon’s Kisapmata (In the Blink of an Eye), a gritty psychosexual thriller inspired by a real-life murder-suicide, which screened at Cannes in 1982, had been restored in 4K. It had long been a favorite of mine, but I had only seen it in a low-res, blotchy digital scan sourced from internet forums. Excited to finally see the film as it was meant to be seen, I reached out to De Leon for an interview. The famously elusive filmmaker declined at first, but had a change of heart after a few weeks of correspondence, which resulted in a conversation published in Filmmaker Magazine that December.

Since then, I’ve remained in touch with De Leon and have collaborated with him on various projects, including his upcoming book about his family’s life in the movies, Last Look Back. With the Museum of Modern Art currently presenting a near-complete retrospective of his films—alongside a selection of classic Philippine works produced by LVN Pictures—I reached out to De Leon for another interview. We discussed his memories of the First Golden Age of Philippine Cinema, the integral role his family played in that history, and how his next film will respond to the political situation at home.

How did distribution work with LVN films and Philippine cinemas through the years?

At the peak of LVN, the studio released one movie almost every two weeks. It was like a factory. My father told me that they had headaches promoting films because they were released with such frequency. They were mostly shown at the New Dalisay theater, on Avenida Rizal, owned by my lola [grandmother]. There were only three main movie houses in the Philippines in the 1950s for first-run Tagalog movies: Dalisay, Life, and Center. There were others, of course, but I think for second-run releases only. I remember movies running only for 10 days unless they were big hits.

In general, were Americans still hovering over the Philippine movie industry at that time?

The only American presence I remember was the managers of Kodak Philippines. Kodak was a major force in the movie industry, even up to my time. The general manager of Kodak Philippines was American. They were always at my lola’s birthday celebrations. A bit of trivia: they created the mold of the original FAMAS [Filipino Academy of Movie Arts and Sciences] award statuette. They donated the annual awards. In the late ’70s or early ’80s, Fujifilm took over the sponsorship of the FAMAS. Kodak was furious and did not lend the original mold. So the Academy created a new mold, and the trophy looked odd after that. Still does.

Remember, LVN was really a postwar company, while Filippine Films and Parlatone [Hispano Filipino, Inc.] were prewar and American-owned studios, I think. You can talk about the American influence on Huk sa bagong pamumuhay [Communists in a New Life, 1953], which was C.I.A.-backed. Rolf Bayer, an American actor-director who worked in the Philippines, wrote it and played the American communist patterned after William Pomeroy. When Fritz Lang was in the Philippines to film American Guerrilla in the Philippines, he visited the set of [Lamberto V.] Avellana’s Ang bombero [both films 1950]. Anyway, any American Hollywood big shot was always feted. Even with parties in [our] home.

I read that you attended seminars in color processing, advanced motion-picture techniques, and laboratory work in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. Can you talk about your interest in the more technical aspects of the filmmaking process?

I was very serious about learning about film processing when I worked in the LVN lab. I had a darkroom where I did a lot of experimenting. The logic and technical ingenuity fascinated me. Negative, positive, negative—like life itself. I couldn’t read sensitometric curves, but when the color was exhibiting bluish shadows, for example, I knew from experience where to look for the cause. Not even the Kodak people could help us. It was not in the Kodak technical manuals. I remember telling my chemists, “The shadow portion of the blue curve is out of whack and I know that the bromide content of the soup is causing this. Please compute how much bromide we should add to correct this.” And like kids watching a carnival show, we’d see the blacks slowly returning after the formula was adjusted. I still miss this.

The only seminar I attended was at the Kodak marketing center in Rochester. This was when they introduced the film stock 5247, which would replace 5254. 5247 had a much shorter processing time and would need a new machine. I was among other Asian participants, including the Japanese. Kodak had a prototype of the new machine and told us that the design was proprietary, so no taking of photos. Everybody nodded in agreement, but when we were let into the room, the Japanese started clicking away, even underneath the machine. The Americans could not stop them. It was hilarious. I also visited the Fuji Factory once and spent some time at Agfa-Gevaert in Leverkusen [Germany].

In the short documentary on the making of Itim, you described how, after Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light, for which you were both producer and cinematographer, you learned to shape your filmmaking approach to the resources you had rather than stretch those resources to match your vision. What were some of the ambitions for Manila that could not be achieved with the resources you had?

Well, the worker’s accidental fall [in a climactic scene] was impossible to light because it was just too dim. I thought I could convince Lino to shoot in exteriors, but he insisted on shooting it inside the studio. So I had no choice but to use one of LVN’s arc lamps and point it upwards. The lighting was from below, totally unrealistic. I think Lino eventually began to understand my concern for realistic cinematography. In shooting the black-and-white credit sequences [of daily life in the Chinese quarters of 1970s Manila], I asked Lino to let me do it alone. At first, he was giving me instructions, but I told him this should be left to the cinematographer. I had an idea of how the credits should look, based on many photographs I had taken in the old part of Manila.

Can you tell me about your approach to the opening montage of Aliwan Paradise, which mixes footage from your films and LVN classics with dramatic reenactments? The sequence signals to the audience that your own work and your family’s movies are not spared by your satire.

I’ve always liked historical montages. It’s something I picked up from the Warner Bros. gangster movies of the 1940s, and the films of one of my favorite actors, James Cagney. I don’t like graphics or text explaining the past before a film begins. And I’ve always liked compilation films and the art of juxtaposing disparate images to express or reveal a new meaning. I don’t use storyboards, but the opening montage of Aliwan was supposed to look like a commercial, so I asked Cesar [Hernando, De Leon’s frequent production designer] to help me visualize a condensed version of our history, with a lot of black humor thrown in.

What do you think of the pairings of your films and LVN’s older productions in the MoMA program, many of which were inspired by your book?

I like [MoMA Film Curator] Josh Siegel’s pairings. They would have been more effective if some of the films he wanted were acceptable, quality-wise. There is no film with Nida-Nestor [one of LVN’s iconic romantic pairs, Nida Blanca and Nestor de Villa]. I planned to do a compilation short film of the best scenes from the available Nida-Nestor movies, but I know they couldn’t be projected on the big screen. Josh also wanted Sumpaan [Vow, 1948], to include Susana de Guzman, a woman director. I objected because the film is so awful. I suggested Pag-asa [Hope, 1951], by Avellana. He has the lion’s share of films [due to better-preserved prints].

When we talked about your upcoming feature a few months ago, you said you were writing something decidedly apolitical. With the Marcoses’ return, you have described “a seismic shift in your thinking”—a desire to open your script up to its surroundings, to the return of a fascist regime. You’ve been in this situation before, wanting to make apolitical films but feeling the need to speak up against the country’s corrupt leaders. Does this time feel different?

Yes, definitely. And age seems to be a big part of it. When one knows that his years or days are numbered, one begins to think of life like a story in a movie. You know, you expect to have some sort of happy or pleasant ending. The situation today is hardly pleasant. It’s been proven that the Marcoses are thieves and morally bankrupt people, and this seems to be wired into their DNA. But what is even more unfortunate is how so many people have accepted them or voted them back into power.

A.E. Hunt is a cameraperson, the vice president of Dedza Films, and a freelance programmer and writer with words in Filmmaker Magazine, the Criterion Collection, American Cinematographer, GQ, Rappler, and other publications.