Interview: Laura Poitras

“It will be a story for sure, I just don’t know how much I want to be in it…” The line comes from the journal Laura Poitras kept while in Berlin, datelined to Valentine’s Day 2013, at which point she was still awaiting contact with Snowden aka CITIZENFOUR. You could take the words solely as a journalist’s commentary about structuring a story, and about safety, but they also evoke the existential challenge posed by the surveillance state. For those who are being watched, the government’s collection of personal data amounts to a constant narrative being written about you, without your consent, and subject to brutal, intrusive revision at any time.

Astro Noise—Poitras’s new art installation at the Whitney Museum—charts a narrative, and, with each visitor, creates a new one. Through a constellation of mixed media, spread across rooms and a peephole-lined corridor, the work builds upon the project of Poitras’s three documentary features in delineating post-9/11 experience. And it collapses the public and the private (much as the government does) in illustrating Poitras’s own resulting travails at the hands of the FBI, TSA, and others. Yet as one moves through the artworks, Astro Noise has a way of inducing a heightened state of self-consciousness (and thanks to a couple of feedback-based works, a vivid awareness of the imprint one leaves behind).

Framing the entire exhibition is a giant opening video screen, drawing on footage from Poitras’s installation O’Say Can You See, footage of people viewing Ground Zero in September and October 2001. These are reaction shots in pure, painful form; one shot showing what appears to be a mother talking to her daughter particularly moved me, and found a strange echo when I visited the Whitney, in a woman trying to focus her stroller-strapped child on a wall of inkjet prints depicting signals intercepted by the U.K. from satellites, drones, and radars. Another sort of reaction is shown on the flip side of the O’Say screen: footage of an Afghanistan interrogation.

Like CITIZENFOUR, the upshot to this immersion is a dry-eyed emotion—that mix of awe and fear created by proximity to the power demonstrated by surveillance, and then a deepening feeling of unease that sets in and stays like an ache. Last Wednesday, following the press preview of Astro Noise—which had received its finishing touches just the night before—I sat down with Laura Poitras to discuss the work, together with Whitney curator Jay Sanders.

O’Say Can You See

That first piece you walk into, the footage of people reacting to the aftermath of September 11th from your O’Say piece, really struck me. You just set up a tripod and filmed?

Laura Poitras: There was a sort of pilgrimage that happened down there, and I just filmed the faces. Rarely did somebody make eye contact.

I myself found it hard to go anywhere near there for weeks afterward.

LP: I didn’t go down the first couple days, but then I felt like I really had to. And then I went with my camera. I thought there was actually nothing there to film—but there was a lot to film. It was a really interesting moment to be in New York. There was this outpouring of compassion, a generosity, a kind of “How are you?” Strangers acknowledging each other in different ways. Something that we, people in New York, experienced.

That opening screen frames the entire exhibition for me. It almost seems to encapsulate a lot of the debate that happened—or didn’t—in the ensuing few years: between fear and reason, in our policy response to terrorism.

LP: What you said about it being an extended reaction shot totally resonates. But I don’t associate those reactions with the government’s reactions, or the government’s actions, actually. Because I felt like in those faces you see a real sense of compassion and openness. Not a sense of vengeance—you just have anguish. They’re faces in anguish and disbelief. And I’m interested in them as images that you can read into and try to understand that moment through. I feel very different when I think about the policy directions that the government has taken in the aftermath of 9/11. I put them in separate categories. Had the government made different decisions, we would be in a different place in the world right now.

There was the hope we could expect our government to act more rationally than a mob might.

LP: Right, and in a weird sort of reverse, the government was making plans to invade Iraq while people were just trying to make sense of what had happened.

Then the flip side of that—and the flip side of the screen showing WTC site spectators—is the screen showing interrogation footage from November 2001 in Afghanistan.

LP: What interests us in terms of formulae is exactly what you’re saying: the flip side and shifting perspective, from this [first] set of images that maybe you identify with or can relate to. So, that was filmed in Afghanistan after the war started. It’s always a dance in non-fiction filmmaking, the line between exposition and what I want to be more experiential. We didn’t put things like wall labels all over the place. We want it to be something you have to explore and experience.

Jay Sanders: And that was deliberate, that our confrontation is first with the visual material, with the room, the choreography, the space. Then we have this brochure which is supplemental to help people orient, but would trail their discovery in real time.

The choreography strikes a chord with the corridor of peepholes—each of which opens on a document, or interview footage, or something else you can’t quite positively identify. You enter a room full of people peering into glowing holes in the walls. For example, one peephole just opens on a shot of a forest. Where is that?

LP: Again, we wanted to leave a few things actually a bit more mysterious, and experiential.

Is the forest something that cannot be identified, or is it just as an anonymous forest?

LP: It has personal meaning… I knew when I first started talking to Jay that I didn’t want to make a work that viewers would have a passive relationship to. And I wanted it to have a narrative so that there would be a way that you enter in, and another way you leave. And there’s some sort of arc and some kind of reveal, like typical narrative tropes. Discoveries, reveals, challenges. Choices. So we started dividing up into these rooms, and I started crafting out the different sorts of works and then realizing that it was drawing upon a lot of cinematic language like the reaction shot, which is like an opening shot. Or the peepholes being an early cinema reference. And so we discovered at some points, Oh, wow, this is sort of a lot about cinema. And it’s also about seduction and all the ways in which cinema can work.

JS: And often in each room the first thing you see is the other people, and that orients you to a different view and condition.

LP: It’s the choreography of people. People saying, “What’s going on here?”

Bed Down Location

Before that corridor comes a room called the Bed Down Location, a room with a platform where visitors can lie back and gaze at the ceiling, which shows time-lapse recorded images of the sky. That’s another space where you’re choreographing people, into a position of vulnerability: a restful, star-gazing position. Were there any other permutations you considered for this portion?

LP: And at some point we did spend a lot of time seeing if live feeds could be possible from different places. But to get something that was beautiful and that was reliable for three months, the technical people said, “That’s really tough.” I felt that I wanted quality but also that cinematic beauty, and I couldn’t get both. So I went cinematic. But all those kinds of things are very much what I was interested in—asking people to slow down and contemplate parts of the world where drones are flying, and then flip that.

About the various documents that are on display, have they generally been available before now?

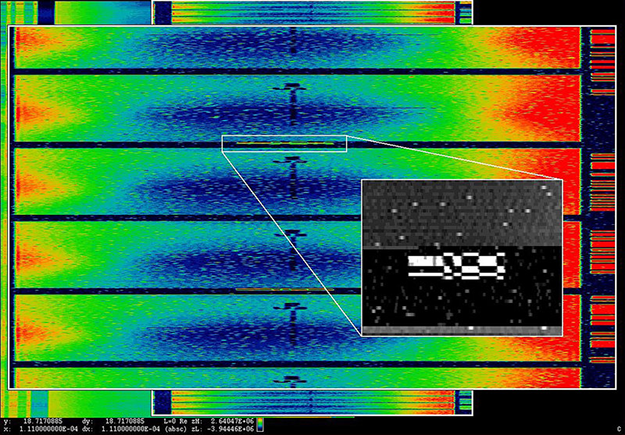

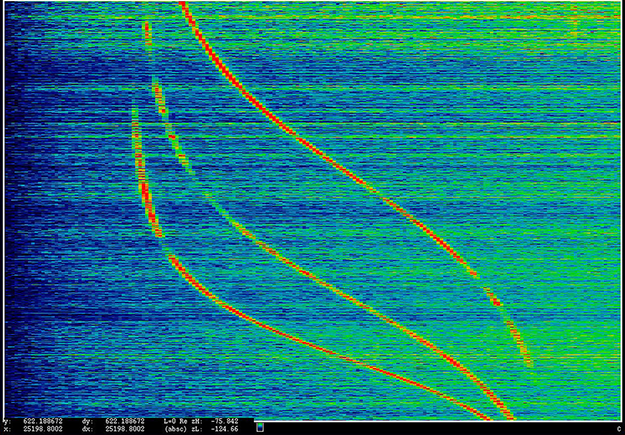

LP: There’s a range. One concurrent news story that was published in relationship to the exhibition is around this program called “ANARCHIST.” And that’s a collaboration between a journalist Henrik Moltke who worked with me in Europe. We started discovering these images that I think are striking visually but also have these striking backstories. But it took us a long time to figure out what the program was and what it did. And that journalism was done by Henrik and his colleague Cora Currier at The Intercept, about the Anarchist program which is intercepting signals in the Middle East, and they focused on intercepting Israeli signals. Then we started to find out that GCHQ is hacking into signals, Israeli drone feeds, and collecting them and decrypting them.

In some of those images, you see actual drones, and others are signals that are in various stages of being descrambled or decrypted. So that series of images that are classified went through all the sort of standard journalistic processes. So Henrik and Cora did the reporting and spoke to all the named parties, and wrote the story and we published that before the exposition opened because we felt that it was important the information be out there. And there were several documents that are in the show that went through the same journalistic process: we confronted the government, and we said, “We are going to be including this in the exhibition.” They know that this is happening. We redact, in general, names that I don’t tend to publish in my reporting unless it’s somebody at a high level.

There are some documents in the show that haven’t been revealed before. But it’s gone through a lengthy journalistic process that’s been led mostly by Henrik and gone through the legal teams with the Whitney. And this experience is very similar with what I did with Citizen Four.

ANARCHIST: Israeli Drone Feed (Intercepted February 24, 2009)

And what about the FBI documents about you that you obtained?

LP: The FBI documents are in a different category. Those I didn’t receive through a source, they were received through a lawsuit against the government—a FOIA lawsuit that was also very much a part of this exhibition. I knew the date for the show and I wanted to see if I could get my files, and it was actually inspired by the writing of William Vollmann. He did this great piece for Harper’s called My Life as a Terrorist, where he discovered that he was a Unabomber suspect, and he got his FBI files and wrote this really fantastic play about discovering his files. I was inspired to get my files and I reached out to his lawyer, the same one who’s very good at getting FOIA documents. He works for Electronic Frontier Foundation, who agreed to submit requests for my files to the government. The government was not responsive in most cases. Then we sued the government, as you’re able to do under FOIA law, and I started to receive documents.

So far I’ve received 800 pages of government documents of my file. And they started coming in October, right in time for the show. The FOIA lawsuit I consider part of the artwork. Those documents and those redactions were not made by me, they’re made by the government. The big surprise in the FOIA stuff was that there was a grand jury investigation that I hadn’t known about. And the level of surveillance that I was under, by FBI and NYPD.

The FBI documents are posted next to a loop of some footage you filmed in 2004 while making My Country, My Country that aroused the government’s interest. And your voiceover, which plays next to the FBI documents, has this amazing line: “It took me 10 years to learn what happened to me.” Could you talk about the temporal experience of working through all of this?

LP: As a verité filmmaker you’re always going in the dark—not really knowing until you zoom out what you, what the story is. The filming at Ground Zero becomes the beginning of a body of work that I didn’t know was going to be the beginning of a body of work. And in a way that’s a kind of chapter close to that.

JS: And that line in your recording, “Those eight minutes changed my life.” Some very banal minutes of real-time footage have such a vastly different meaning in the context of the story.

LP: Yeah, and as a narrative piece, you could also talk about it as an inciting incident. Everything else that’s in the show goes back to those eight minutes. But it was one piece that I struggled with: “Do we hide it, do we make it concealed?” There was a part of me that wanted to make it really hard to find.

O’Say Can You See

Jay, what were some analogues or points of reference in thinking about this show?

JS: It’s unique. I love artists that really redefine things from the ground up—the space, the conditions. You need a maximum amount of control of all the variables of the experience in order to really do things that can be as unsettling or euphoric or transforming as they can be. So Laura’s way of working, we’re sympathetic in that way. You could talk about the history of cinema or the history of expanded cinema, which is something that the Whitney has a lot of history about with Chrissie Iles and that sort of thing. Something like that Into Light show that was 15 years ago—that show blew me away when I first came to New York, and saw Michael Snow and that generation for the first time. That was new to me. And I’m always interested in what you can do to take the conditions of your medium and extend it sort of beyond what it’s meant to do or something. This show updates those potentialities for how a moving image can situate itself and what it can ask of viewers. And also how you deal with documents, factual material, but create situations that allow for very different point of entry.

LP: I studied that tradition, in Michael Snow or Warhol’s work, and I love what they did in terms of pushing the boundaries of cinema. I remember seeing Chelsea Girls, and it was just like, “Wow!” But for me, the resonance of doing installation work is actually how do you use the space in an emotive way—not just making it an intellectual experience but that it’s another physical experience. And then I go to a different tradition than expanded cinema. Installation work like [Christian] Boltanski, who’s been constantly working with materials and histories to evoke with the Holocaust. It’s very emotive. You experience it.

Jumping back to the FBI file again for a moment, I like how they refer to you in the document as an “independent media representative.” And I thought, “That’s not wrong.” [Laughter] What’s the situation now for you in terms of surveillance?

LP: You know, with the government, you can’t just call up and say: “What’s the status of my watch list?” It’s not information that’s been forthcoming. Nor has the government ever chatted with me about why they put me under investigation. So I don’t know. The one thing I do know is that they stopped detaining me at the border, but that doesn’t mean you’re off their watch list. They have something that actually one of the documents talks about. There’s no-fly, selective—which means harassment, questioning, I was a selectee for many years—and then they have something called Silent Hit.

Who comes up with these names?

LP: Silent Hit means they don’t stop you [at the airport], so you don’t know, but it’s like a silent hit. So I don’t know if I’m no longer on the watch list or if I’ve moved to the Silent Hit list.

That brings me to another aspect of the work, which is finding ways of representing or figuring bureaucracy. Because for this stuff, you don’t get to see or talk to somebody face to face. In terms of surveillance, have you ever talked face-to-face with anyone in the government who has explained anything whatsoever to you about this? What’s so completely vanished is any physical interpersonal experience, any actual face-to-face interaction.

LP: The answer is no, which is probably what motivates some of the work. Particularly the dispositions of the peephole boxes. It’s that there are forces that you can’t quite understand that are acting and that are having impact—but they’re not approachable. They’re hard to see into. I’ve had the effects of it but I’ve never had, “These are the personal records we’ve obtained from you.” I don’t have any idea. So the closest I’ve gotten to it is the FBI documents. They’re disturbing, but there’s a sense of appreciation that I have more insight than I did before, which actually feels like a good thing. Even if it doesn’t feel necessarily good to know the extent to which I was put under investigation.

ANARCHIST: Power Spectrum Display of Doppler Tracks from a Satellite (Intercepted May 27, 2009)

There’s a strange way in which those FBI documents actually add a human element: you see a certain amount of narrative, you can picture someone.

LP: Right, right.

But it’s probably not very satisfying.

LP: I’ve said it a bunch of times before, but I really feel like it is a kind of bureaucratic machine that you get caught in the grinders of and then its very hard to get out of. It sucks you into its mechanism, and it has happened to other journalists—James Risen reporting in the subpoenas, the Grand Jury stuff. You get too close to it and it’s gonna pull you into its vortex.

I wanted to ask what you’re working on next, and specifically whether you’ve been considering any kind of work in virtual reality.

LP: Right now I’m really focusing on Field of Vision and the commissioning of short-form, which can be responsive to events. I’m helping to executive produce and send filmmakers. So I’m definitely really deep into that right now and loving it. AJ [Schnack]’s piece about gun violence is using form in such a way to really make a point but also to think outside a locked structure. It’s structured in such a way that the film will get longer if there are more mass shootings.

I find virtual reality to be very isolating—maybe I haven’t had the right experience. If virtual reality can get there, I’m all for it. I’m all for it expanding, shifting different types of storytelling. That’s what I think I’ll be doing for the next foreseeable future—working in different formats.

And finally, to take a step away from the work, I was wondering what else you may have been watching and enjoying.

LP: You know what I love? Mr. Robot. It’s really smart storytelling. Once I got it, I was so hooked, it was hard not to keep watching it. So I’m definitely a Mr. Robot fan. You should see the coverage, the angles they get. The opening scene in the second episode is so good. And all of it is in voiceover acting. I’m glad it’s coming back for another season. It’s like really smart cinema.

Astro Noise runs through May 1 at the Whitney, accompanied by a full calendar of events and the exhibition’s anthology catalogue, which includes excerpts from Poitras’s Berlin journal and a short piece by Snowden.