Interview: Jennifer Kent

In her follow-up to 2014’s The Babadook, Australian filmmaker Jennifer Kent sets her sights on horror(s) of a very different kind. The Nightingale, set in Tasmania in the 1800s, opens with the brutal rape of an Irish woman at the hands of an English lieutenant. As the woman, Clare (Aisling Franciosi), sets off on a quest for revenge, enlisting the assistance of an Aboriginal guide named Billy (Baykali Ganambarr), the film morphs into a sprawling and deeply moving critique of the ravages of colonialism. To bring together these distinct (but connected) narratives of gendered and racist violence is an ambitious prospect, but Kent takes on the challenge admirably, pushing her film into unexpected, uncomfortable, and often audacious places. She’s aided by the layered and revelatory performances of her lead actors, the fiery-yet-flawed Franciosi and the wounded-yet-proud Ganambarr.

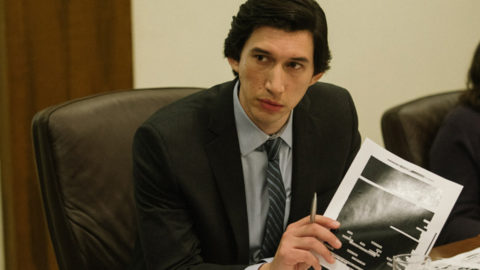

Soon after the U.S. premiere of The Nightingale at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, Kent chatted with me about her approach to filming rape, her collaboration with the Aboriginal community to tell this story, and the challenges of making difficult and provocative films as a woman director.

What made you want to tell this story?

I think ideas come from a place that is sort of not definable. I was actually reading the Mahabharata at the time, and there’s a character, Ambika, who is full of rage, and she reincarnates to murder someone that has done her wrong. I was enlivened reading this, not because I love the idea of vengeance, but I thought, ‘Wow!’ It really struck me. And at the same time, I was also very disturbed by the level of violence in the world. It’s not an intellectual process, how a film comes to me, but through these things that I’m doing and feeling, I wanted to tell a story about the need for love in dark times. I guess I wanted to ask the question: Is it possible to really love and grow in kindness, compassion, and empathy in really dark times? And the idea to set it in Tasmania was simply because that’s my country, and I wanted to make it relevant to me but also tell a story that’s universal.

There’s been a lot of conversation and writing about the filming of rape—some people consider it to be voyeuristic and others feel that it’s the sort of reality that needs to be captured unfiltered. What was your approach to the brutal rape scene at the beginning of the film, which essentially sets up the rest of the story?

It’s curious to me that people distinguish between rape and violence and put them in separate camps, because rape is violence. In terms of it being voyeuristic, well, it’s all about motivation and how you film it. So it’s more about your approach than saying, “To include a rape in a film is voyeuristic.” And to turn away from these issues, which are so important to shine a light on, would be foolhardy. Unfortunately, sexual violence is a really big part of life, as we have seen across the world. I knew I was dealing with something very important and I treated it that way.

In the making of, I wanted to put the audience with the person experiencing it. So, rather than being voyeuristic, I think it’s experiential. People at Q&As and other journalists have said to me, “Oh, your rape scenes are really graphic.” And I say, no, they’re not graphic, because they do not show anything besides human faces and human emotions. I couldn’t find a rape scene anywhere, actually, that didn’t show a woman’s body. So I was adamant that I wouldn’t show the woman’s body, that I would show the crux of sexual violence, which is one human being annihilating another. And that can be read through what’s going on on a person’s face.

I’m very proud of those scenes, and I don’t apologize for them. If people find them confronting, good. Because we need to look at this. It is a painful act, it ruins people’s lives, and some people never get through it. And that’s my point, you know? Yes, it’s hard to watch, I really acknowledge that, and the only time I would perhaps suggest—not apologize—that people don’t see this, is if they’ve had really terrible things happen to them that makes them just not want to be in this space.

What is really fascinating to me about the film is that it starts out as a rape-revenge drama, but then it turns, somewhat unexpectedly, into a story about colonialism. How did you see those two things coming together like that?

Well, colonialism is a mindset and it’s a violent one. It is, by its very nature, a brutal construct. And the violent mind that created colonialism is the same violence that exists in the world today. I don’t distinguish between what happened then and what’s happening now in the world. But I guess I didn’t set out to tell a political story. I really wanted it to be a story about Billy and Clare, and you can’t avoid exploring colonialism within that story because they’re both suffering from the extreme fallout of it, and they’re both the walking wounded. Yes, there’s that intense desire for revenge, and the rage and single-minded focus that it brings, but then when you play it out and it doesn’t give you the kind of fulfillment you need, what are you left with? I was more interested, in the second half of the film, to explore what that is. To me, the fact that Billy and Clare can connect from one human being to another after what they’ve been through is a beautiful thing. It’s a miracle. So colonialism is there [in the film], but it comes through the characters.

I think Billy and Clare’s relationship goes into some really tricky terrain, because when you bring together a white Irish woman’s experience with that of an indigenous man, there can be some false equivalencies—especially because depictions of white feminism often occur at the expense of people of color. But what really struck me was that despite everything Clare goes through in the film’s opening sequence, she still gets schooled. She is actually undercut by Billy several times.

Yeah, we really did not want this to be the white savior narrative or the sentimentalized idea of a black man’s pain facilitating a white woman’s journey. They both have their own agency, I hope, and we worked really hard to make them both complex characters and to show their damage on screen. It’s not just a white woman’s story, and in order to achieve that, we needed to enlist the help of Aboriginal people. And we did. We had an Aboriginal consultant from the get-go, an Aboriginal Tasmanian elder. But you know, I wasn’t going to tell this story at a certain point, and—

Why so?

Well, because I didn’t feel I had the right to. And I approached him and gave him a synopsis, and he said, ‘I can’t not be involved.’ He said, ‘It’s a shared story, and you have the permission, as long as we work together.’ And we did, we worked closely with the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. So we did what we could to make this a shared story and yeah, I think it is a complex issue. But then if you don’t tell this story, who would tell it? I think ultimately what the story is saying is that hopefully we can transcend these barriers. Not in any kind of sentimentalized ‘we’re all the same’ way, not at all, but at the end of the film, there’s one human standing in front of another human and there’s love there. And that’s all that matters.

Can you talk more about how exactly you worked with the Aboriginal community?

Well, we have the Palawa kani language in the film, which is a reconstructed language from existing records. There were eleven nations, I think, within Tasmania that each had their own separate languages, and so Palawa kani has been drawn from the records of these languages that were lost. And Tasmanian Aboriginal people speak this language today, it’s a living, breathing language, so we used that in the film, and we had a Tasmanian Palawa kani expert on set. Jim [Everett, the Tasmanian Aboriginal elder consultant] went from the first draft to the final and gave feedback. For all of the rituals and songs, Baykali Ganambarr [who plays Billy] created the melody lines used, and the words that he sang were offered up by Jim. So there’s nothing in the film that I decided, “Oh, I’m going to put this in because I like it.” No, it comes from their culture, and that was really important to me and the producers. Jim was there on set for everything, down to costuming, casting, how the rape scene of Lowanna is carried out… there was meaningful input at every level.

I thought it was interesting that you included Lowanna’s rape scene, because sometimes, in these stories, it’s the women of color that get lost. I don’t yet know what exactly to make of it, but—why did you think that scene was important to have in the film?

Well, it’s a tough thing, but the reality of that time is that there was a war called the Black War, and it was waged over the abduction, rape, and murder of Aboriginal women. So, if I make a film like this and don’t show that reality—I think that’s worse than showing it. And for that scene, I worked very closely with Magnolia, who plays Lowanna—she’s really dedicated and she understood the reason it was in the film. I thought it was important that people see that these people are not just natives running around the bush and throwing spears, but they’re humans that lost their children, that were just abused and then discarded, and it’s a really tough thing to watch but it’s necessary for this story.

The film is structured, in a way, as a chain of acts of escalating violence. But when it gets to its zenith, you abandon that conceit. When Clare actually sees her abuser, she’s paralyzed—she can’t do anything. I thought that was very tender and moving.

It’s interesting that you say that because some people find it frustrating. And I think it’s hard, maybe, for people who haven’t been abused to understand the paralysis that comes about when you’re face-to-face with the person who has taken away your soul. We had a clinical psychologist involved in the film, and both Aisling [Franciosi] and Sam [Claflin] read a lot about the nature of abuse and the hold that the abuser has over the victim. And this is very common behavior among women who’ve been raped. I have no problem understanding that, and I, too, feel very tender towards that, because we’re so conditioned by films to believe lies of heroism in revenge stories, seeking justice and all that… it’s all sort of rubbish, really. Humans are not like that. It’s hard being human. So yeah, it holds up from a psychological perspective, it holds up from a trauma perspective.

Can you talk a little about the visual language of the film? It’s stark, but also very lush and attuned to the rhythms of the countryside—you’re trying to capture both the inside of the protagonist’s mind and the terrain this drama unfolds against.

We used the Academy ratio because it’s a more emotional ratio, and when you’re moving humans through landscape, you need keep it connected to the human. Also, just logistically in Tasmania, the trees are very tall and there’s a lot of depth in the forest. It has a mythical quality, and I wanted the film to feel mythical, too. And I understand the way people think of it as untrue—I mean, this is a story that has a heightened quality that turns it from a period film into a universal story. That’s what lights my fire as a filmmaker. Every choice we made in the filming of it supported that mythical quality. I hesitate to use the word “fairytale” quality, because it’s dealing with such tough subject matter and with true history, but it’s not naturalistic. We actually had 150+ locations and I drew up very, very detailed maps of what I wanted each location to look like. It’s very interesting that you picked up on that, because that was my intention, to have each location reflect something of Clare.

I know this is just your second feature film, so I don’t want to make grand, overarching statements about your work yet, but so far—why this proclivity toward horror? Because I would say that this film also has certain elements of almost classic horror.

Right. I don’t think in terms of genre, really. I gravitate towards stories that I cannot not tell, like I can’t shake them off. I think I’m interested in stories that explore light in darkness, and I guess horror does that. Horror is also very cinematic and heightened in its qualities, it’s often quite expressionistic in that you feel what you see. I don’t see this as a horror, per say, but I understand what you’re saying. I’m not interested in the definition of my work; I’m happy for others to do it, but it doesn’t help me. My next film is also quite heartbreaking and dark, but full of love, too. I think my films are love stories. [laughs]

Are there any guiding inspirations you have in terms of other filmmakers or certain texts?

Yeah, I love David Lynch, because he also defies classification. I really love that about his films. There are many filmmakers that I admire and films that I love, but in terms of his bravery as an artist, he’s probably the most inspiring to me. It’s a quality that is getting rarer in film, because it’s getting harder and harder to make a film like The Nightingale—independent films with a singular or a stubborn vision, which is not about pleasing a target audience. So I look to people like Lynch for inspiration.

What’s your next film?

It’s called Alice and Freda Forever‚ and it’s based on a true story set in Memphis in the 1890s. It’s a love story between two teenage girls, based on the book of the same name. That story’s captured my heart and I’m excited to leap into that next. I’ll probably get criticized a lot for that as well, since it’s dealing with same-sex love… but you know, you can’t not tell stories because someone might be offended, because then you will never tell any story.

I think being a woman filmmaker also maybe just puts you at the receiving end of more of these kinds of criticisms.

You think?

I think so. Just look at the canon of male filmmakers who’ve made films glorifying all kinds of violence; they’re written about very differently.

Oh yeah. I know why I made this film, and I’m proud of it. Those things can hurt for a short period of time, but the film transcends everything. Venice was quite tough, being the only woman. I’m lucky I was brought up in a household where I wasn’t defined by my gender or made to behave in certain ways, so it was a real shock for me to go to Italy and be defined constantly by my gender. With journalists, over and over, the only question was: “So how does it feel to be the only woman in competition?” Over and over to the point where I just got angry. I just kept saying, “I’m an artist.” Every artist just wants to be seen as an artist, as an equal. No one would say, “So, how does it feel to be a male filmmaker?”

And I got that comment, too—not even a question, just a comment, “You know, it’s the most violent film in the festival.” And I thought, well, there’s a lot of love in this film, too, and there’s a reason for the violence. Just watch, just think before you speak. I feel like a lot of people in Venice didn’t see the film I made because it was under this cloud of gender. But you know, you survive it, and the film will outlive those comments.

Devika Girish is a freelance film critic. She grew up in India and currently lives in Los Angeles.