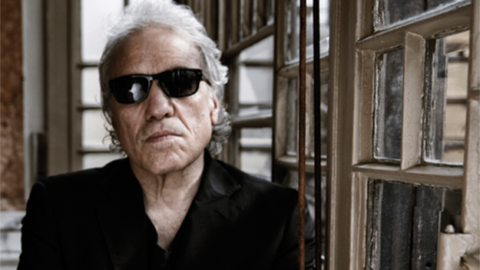

Interview: Gérard Depardieu

Gérard Xavier Marcel Depardieu was born to a working-class family in Châteauroux, smack dab in the middle of France, in 1948. At age 16 he came to Paris, had an early stage success in the Café de la Gare troupe, and soon found himself mixing (and guzzling) with the leading lights of the French stage and screen. He made his own film debut as a nervous, stammering young door-to-door salesman in Marguerite Duras’s Nathalie Granger (1972), and in the interceding years he has appeared in approximately 400,000 movies. Some of these, including his multiple collaborations with Maurice Pialat, rank among the finest French films of the talking picture era. One of them is Bogus (1996), in which he plays the imaginary friend of Haley Joel Osment. More recently he will be seen on American screens in a small but potent part in Claire Denis’s Let the Sun Shine In, playing this weekend at the New York Film Festival, in which he packs more depth of feeling into one disappointed exhalation of a line than most actors could get out of a meaty monologue.

When I met with Depardieu on the patio of The Mark Hotel in New York on an overcast morning in mid-September, he was markedly disinterested in talking about any of his movies, in town as he was for a talk at the French Institute Alliance Française to promote his slender new book, Innocent. The book is more scattershot manifesto than autobiography, its title a double meaning—its author both describes his personal philosophy, of which a doctrine of innocence is an essential element, and protests his own innocence before an imagined jury of the media, who have made tabloid fodder of him. Topics discussed within include the milquetoast quality of much contemporary art, the impossibility of marriage, the Russian right to Crimea, and the globe-trotting Depardieu’s claim to be able to understand people the world over despite his frequent inability to actually understand their language.

The last point I fully believe after sitting down with the author, for never have I had an interview which suffered so much in transcription for the inability to convey facial expression or gesticulation—I will say only that Depardieu pantomimed humping three times during the course of my brief audience with him, and that it was funny every time. In spite of the absence of these embellishments, the discourse of a living folk hero must be of some interest.

Let the Sun Shine In

Discussing your method as an actor in your book, you say you don’t have one. Are you different as an author? Do you pre-plan when writing?

I dictate. I dictate the way that Alexandre Dumas dictated, but now it’s simpler thanks to computers. So I dictate. I talk, and there’s a person that transcribes it, and I correct it with that person. Before it wasn’t easy for me to talk. I didn’t speak easily. I found speech with the theater, especially the classics. When I said the verbs out loud, even when I didn’t understand what I said, I knew the music of the verse, of the Alexandrine. It was this Algerian man who was a professor of literary Arabic who showed me how to refine the language: he showed me versification, he showed me the 12 feet, by teaching me about Corneille, about Racine, who made this huge change in the French poetic language, using only 200 words to make his tragedies.

In terms of structure, did you have an idea that the book was going to have this thematic breakdown, or was that something you came to in the process?

I wrote it as I went along. Before, I had written a book with someone named Lionel Duroy called Ça s’est fait comme ça because I was sick of what journalists were saying about me, about every speech I made. I did another book between the death of my mother and the death of my father. There were two months in between their deaths. I had a friend who was a journalist who said, “You should write letters, because you can’t say to your mother what you think. I couldn’t say ‘I love you.’” In my education, we didn’t say that kind of thing. So I wrote the first letter for my mother, and after, I wrote some for some other people I know, like Marguerite Duras and François Mitterrand. And at the end when my father died, I went back to my home and I found a cat. My father loves cats. And so I wrote another letter for him. The book is called Stolen Letters.

I’m not a writer. I realize the difficulty that there is in writing because I have good friends who are writers, like Duras or Peter Handke. With Marguerite Duras, it’s a little bit different. I recognize with her that there was this inner world. Many writers invent stories around an emotional truth that they have, but that’s not the truth. And that’s very interesting. She wrote a wonderful book called La Douleur, about World War II. When François Mitterrand was opening up the camps at Auschwitz at the end of the War, he heard someone calling “François… François…” It was Robert Antelme, Marguerite Duras’s first husband. She took the time to write that book when she was an adult. But she was special, Marguerite Duras, she was very monstrous. But you also have Françoise Sagan, who was wonderful. She was more romantic. She lived very fast like a shooting star. Sagan became very famous, very young, but then she had to bear that fame, she had to lift it. But I knew all these people very well, these people who wrote.

This runs through the book, an enormous interest or attraction to big, unwieldy, dangerous personalities—be it in theater, be it in literature, wherever you encounter them in the arts.

It’s the only interesting thing. It’s the only living thing. The rest is just a copy of life. There’s no courage; there’s nothing artistic in it. It moves me. I love the monster that the artist creates. But I love normal people, to see how they live. I’m like a voyeur of people’s lives. When I’m in New York City, I’m not interested in going to the very expensive restaurants where you pay a lot of money. What I like is to go to this barbecue restaurant in Harlem next to the Cotton Club. There, I see life. People’s eyes speak to me. Not like the voices you hear on television. Even Obama, even Clinton, even Jimmy Carter, even Bush, all TV news—they always lie, and you can see that. We get used to the lying, even in France, on the news. Power makes people completely different. In four years they get old. When Obama started he was full of energy, then little by little his hair becomes white. It’s absolutely awful to live life between cameras, where nothing is real. It’s always propaganda. It’s the same thing that the Nazis used for Hitler’s propaganda. Any political person, any politician, needs propaganda, and there is where we enter into lies.

You talk about in your first chapter your friendship with French actors of a previous generation like Marcel Dalio, Jean Gabin, Michel Simon. The point you make is that this was a time, I’m quoting, when “you could live your passions and turn them into art.” You seem to feel that the ability to live in an outsized way has been curtailed now, hemmed in, by a media-enforced propriety that makes it harder and harder, in your view, for those sorts of personalities to thrive and exist.

It’s harder. And also, when I was young, I was full of hope. So I tried to have some fathers, some role models for that kind of life, these guys who dared to be against all the power that existed. Marcel Dalio was Jewish, so he had to hide during the war. You know, he was always in his makeup. He had been to America and had a career, and he later told me, “You have to say ‘Yes,’ even if you don’t understand what they’re saying. You say ‘Yes.’” I did my American career without language, but I said “Yes.”

Cyrano de Bergerac

I detect a little language.

In America I was nominated for an Oscar for Cyrano de Bergerac [1990], after I had won a Golden Globe for an Australian film I made with Peter Weir [Green Card, 1990], a comedy. To be nominated for the Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Comedy in English, and I didn’t speak English. My character was named Georges Fauré, and I lied all the time in this interview to get a green card. Peter had that idea. Andie MacDowell’s character was a middle-class [environmentalist] and absolutely wanted that apartment with the greenhouse, so she had to get married because the building [co-op board] said, “We want you married.” She had a boyfriend, but the boyfriend didn’t want to get married. So I was really disturbing this young woman who was of the American bourgeoisie, that’s an idea that Peter Weir had, and it’s a really fascinating idea. When I refused, because they didn’t want to give me the green card, I said, “I can work here without the union, so I don’t need a green card. I work when I want. I’m a citizen of the world.”

And I’m not a citizen of France. I never thought I was French, although I speak French, and I’m from the culture of France, taught by an Algerian who was a professor of literary Arabic, and he taught me French and all the difficulties of French grammar. And after all, I learned this from all the French authors, but also Shakespeare in translation. Though I never trusted translation. Even if it’s great, it’s always translation. It’s exactly the same for William Faulkner. Before, he worked for the studio, and the novels of Faulkner were very strong. Robert Duvall was in the very beautiful movie of Tomorrow, about the young girl who was raped by the brothers and sisters. It was an amazing movie, black and white, 1972. Bob Duvall said, “Why did you buy [the distribution rights for] that movie?” And I said, “Because I wanted to show it in France.” That you have your tragedy, like Marcel Pagnol. It was part of a small region of America.

You mentioned Cyrano just now, and I know it’s a role that’s been important to you, as you quote from Cyrano in the book. It occurred to me while reading, and maybe you’ve heard this before, that the book reads very much like the expression of a disappointed romantic.

Disappointed. Of course. But Cyrano couldn’t be a less American character. American characters are very proud. Cyrano was very ambiguous, because he hates himself so much. He never wanted to have a rank. He had big problems with his ambiguousness, with his homosexuality. It’s very strange. That interests me deeply, because there are a lot of people who are homosexual who don’t go there. Even in America. Very, very often, with the beautiful actors, between James Dean, Monty Clift, Rock Hudson. A lot of people who were like that, and that ambiguity for me… we have to defend our ambiguity. And it’s not a sin to be homosexual!

A Frenchman, named Guillaume Thomas Raynal, who did the manual of the French Revolution in 1789, wrote a book about America, the Histoire philosophique des deux Indes. He was a Diderot-like journalist, who recorded what Paris was like around the end of the 1700s. The small road around Paris, in all the bars, he’d send his journalists to listen to people—and hardly insignificant people, these were philosophers. He invented journalism. They were philosophers, but they invented journalism. These journalists went everywhere. They went to the convents, the bars, the places where workers were. They collected all this stuff, the heartbeat of France in this period, that comes after Louis XIV. Now, Louis XIV had a brother that people would call “Madame,” who was a notorious homosexual, so this was a part of the history of France going all the way back to Henry IV. All these kings had mistresses and bastard children, and the church tolerated this.

It’s very Christian. It’s the guiltiness of the Christians. The pedophiles of the church, they push the innocents to have a secret between them and God, and between the priests. To be innocent is the best way to not see the sin, the fault. The Bible says, “To the innocents with full hands.” And you know I met some people who were abused. It’s very hard to leave when you are in on that secret. But forget the secret. You have that experience. If you love the church: go, continue. But if you don’t love that, it’s finished. They make you believe that the secret was between him and God, God was the witness. But I don’t know who God is. I’ve never seen God. I’ve never seen a miracle. I’ve never seen a woman get pregnant without a dick, without making love. I don’t believe that.

One of the points that keeps cropping up is that you’re very hard on those you view as hypocrites, tightasses, what have you, and you speak at one point about the cleanliness that you believe all of us in the West are dying of. Do you think that that hypocrisy, that cleanliness, is still rooted in the church? Because my impression is that France is increasingly a secular country. Do you think the nature of that cleanliness has changed?

I think that since the Crusades, ordered by the Christians in the 10th century, all religion became politics. Before the Crusades, in Córdoba, for example, in Spain, you had Jews, Muslims, and Christians who were in full harmony. Or think of the Jew, Maimonides, who was the doctor of the great Saladin. There is no religion. The Christians, in the name of Jesus Christ, led the Crusades, and after that everything becomes political, and at that time, a lot of people change.

Green Card

There are a few words that recur throughout the book. One of them is “politics,” which you seem to have a uniquely disparaging definition of, and it’s contrasted at different points with “religion,” true religion, in which you denote an interest; or “history,” in which you obviously have an interest. But “politics,” as you define them, you seem to have an across-the-board abhorrence of.

Absolutely. Politics is the beginning of teaching lies and opportunism. I do not believe in politicians; they are the people who are ready to do anything. They would kill their mothers and their fathers. I don’t believe in this idea of someone who is going to do good for others. I don’t believe in ideologies. They scare me. Take Karl Marx, for instance. He’s someone who helped Bolshevism as much as he helped Hitler. It’s the same thing, with two extremes.

At one and the same time—and I want to understand this definition of politics—you’ve had close relationships with figures who, to my mind, would seem to be political figures, like Mitterrand, or Putin, the latter of whom you talk about a fair amount in the book. So how do you make that definition?

Of course. Because Putin gave me a Russian passport. Why? Because France rejected me. The French prime minister rejected me. And it wasn’t only because of taxes, it was because I did not agree with how he was announcing things that were completely unacceptable in a democracy. He was becoming—this is François Hollande—a little Bolshevik, and when Putin heard that I was saying these things and having these problems, he said, “I’ll give you a passport.” Of course, I accepted. But before dealing with Putin, I tried to understand Putin, and how did I understand Putin? I understood him because I knew Russian history. I knew Russian history starting with the prince of the Tatars through Ivan Grozny, who founded the Romanovs. Now Grozny was a monster, like all totalitarians, and this runs through to Stalin, before whom there was Lenin. Stalin became a dictator, and dictators become monsters. Why? Because they must sacrifice, they must purge to keep power, and this continued until 1953 with the death of Stalin, and then Stalin’s executioner came along, Khrushchev, and he gave Crimea to Ukraine, because Khrushchev was Ukrainian, and now today, we have a new conflict involving Ukraine.

But all of this, to my mind, would belong to the realm of politics. The lengthy disposition you give in the book about Crimea, for example…

For me it belongs in history, not politics. Who took Crimea from the Ottomans and France, because the French were with the Ottoman Empire? Catherine the Great of Russia, in 1774 and 1778, fights the Ottomans and France to take back Crimea for Russia. I did Ivan the Terrible, the Prokofiev musical, in Chicago, in Russian, and even if I couldn’t understand every line, it was clear. It goes right back to Prince Ivan Grozny. Grozny means Ivan the Terrible—Grozny, like the city in Chechnya. That’s history. People find arrangements with history. The Americans, in the 1700s, they killed the Indians, but the Indians had been here for years, 20,000 years, long before God told Abraham to count the stars in the sky and after you’ll have two children. But the Indians, who came from China, Iran, Uzbekistan, Siberia, they crossed the Bering Strait. The valley where Max Ernst lived [Sedona, Arizona], he found the theme of the place with Indian designs. It’s amazing: what Picasso did in Africa, Max Ernst took from the rocks, the designs. In your country you have dinosaurs.

Since we’re onto the migratory patterns of the American Indians, you talk in the book about being at Death Valley and thinking on the routes of the settlers. You seem to be very interested in these journeys, and in your life, you seem to be a very footloose guy. The book describes a journey, too—a turning-away from the West.

It’s true that maybe I have a certain feeling for the history of greater Russia, especially the spirituality, these walking monks. Not Rasputin, the Orthodox, the Christian schism. There’s something particular about Russia. It’s because the land is so flat. There are no mountains to stop the wind, so the people are confronted with themselves in the immensity of this land, in the cold. It’s true I’m a little sentimental about Russia. Now, I’m not in agreement with all of the purges, but purges have happened throughout time, all the time. Going back to antiquity, there have been horrors, including in China, even before Mao, or in Japan, this tiny little country, they massacred all these people at Pearl Harbor when they sent all these people that no one would have never expected, doing the same thing as these idiots in ISIS with the bombs wrapped around themselves. This world has always existed. It’s a world of terror, of agony, of barbary. I do have to say, I have a fondness for these ignorant people, the serfs, who even Tolstoy liberated, but they didn’t want to leave. They grabbed onto his legs and held onto him and said “No, no!” Tolstoy, who at 53 stopped writing and embraced religion.

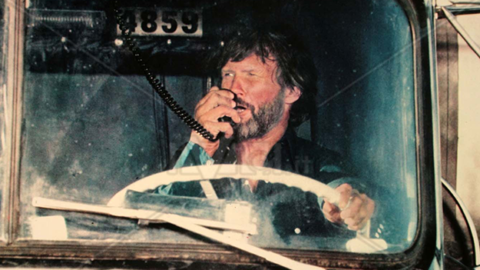

Ivan the Terrible (Chris Sweda / Chicago Tribune)

At the beginning of your second chapter you ask a question which I think is of primary importance to anyone interested in the cinema or the arts generally, which is, “Since when should cinema be benevolent?”

I ask the question because now you see where the movies are, you see where the stories are: it’s only benevolence. George Clooney, Angelina Jolie, Leonardo DiCaprio, and French actors, too, who want to try to save the planet. And you have your president saying… [Distorts face into a shockingly accurate Trumpian mask and blathers incomprehensibly] “I THINK….” You think bullshit. This makes me laugh. All of this makes me laugh. You have all these people who make lots of money, which is fine, very good, but even if you have a lot of money you have nothing to say. Angelina Jolie, who saves the children, she’s like Josephine Baker, she had 13 children of all nationalities. I prefer to make love and to have children, even from a lot of bellies. But, with 10 billion people… Before there were three, four, five, and now we’re at seven, nearly eight billion—of course the planet is tired. One day we’ll have 10 billion, and when there’s too many people like that, we will have new epidemics. Already, the army have new chemical weapons, they’re ready to kill. Because 10 billion people, you cannot live in that. I will say, within 50 years, when we become 10 billion people, there will be a mutation. Already we have mutants. So don’t be blind to that. In China, the policy is to have one child per family. You could think it’s cruel, but this is necessary.

And it’s necessary also to think of different energy sources than oil. Oil is completely new—1961, Kuwait, with British Petroleum… Because the worst are the British. The Hundred Years War, and now they want to leave Europe. I hope the Scottish will stay, the Irish will stay. I don’t trust the British, but I trust the Scottish. Leave the British where they are. They can die alone. I don’t care. I don’t like the British. I’m absolutely French. [Laughs]

For a so-called citizen-of-the-world, you sound very French right now. What was the response to the book back home?

I don’t know. I’m not interested in that. I don’t know because I don’t count the money. I’m not interested. And when I say that, I say it truly. I’m not like Angelina Jolie, I’m not trying to change the planet. I feel that the planet will keep turning without me.

What is the distinction between benevolent art and dangerous art?

Who pays for the art? Before, you had patrons of the art like the Medicis, who had the Pope in their family. You had Francis I for Michelangelo. Now, who are patrons of the art? It’s not Gagosian, because Gagosian is nothing. You have Bernard Arnault and François Pinault in France, who have money, but they don’t have taste. They try to make the value of artists, like Koons. Koons, I respect Koons, because he works with Cicciolina, and he finds that art and sex—it’s okay. So, he did his pieces with that very smart woman, Cicciolina—she isn’t just a vagina, she was smart. And Koons was smart. He did exactly like Rodin did. He multiplicated the artist, and took the best of them. I went to Venice two weeks ago, and it’s disfigured. It’s full of sculptures made of compressed plastic, of monsters from Atlantis. These sculptures are right in the middle of the buildings of Venice, with spotlights on them; it’s a rape. You also have now also the designer, like Felix Stark. He trying to put decorations in Venetian palaces. It’s shit. But I like Koons. Koons knows you have to fuck the stone to find the beauty of the thing.

You talk about this lack of taste in the moneymen with regard to cinema, as well, the lack of brave producers…

Before, in American movies, from 1935 through 1970 with Easy Rider, you have amazing movies, amazing comedy. Lubitsch! Who did Hollywood value? Jewish people who escaped the Nazis. Who makes the box office in Hollywood today? English, like Ridley Scott, Tony Scott, Stephen Frears, Adrian Lyne. There are very few Americans who make the box office in American. You have your genius Walt Disney, but now Walt Disney is passé. And with Chinese directors like Wong Kar Wai, Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige—they’re refused by the American industry. I’m not against the industry, but I also recognize when you have, for example, 5,000 movies from 40 countries, and America they did maybe 900 of those movies, and it’s not like India, where they’re telling the stories of 1,200 castes. And so the movies are the same. And now, they want to make you believe in the X-Men… Dr. Strange… No. Before, there was a strong literature of science fiction, in 1935, science fiction was great. But now they’re trying to do more Avatar? Avatar. Very good for the children of a generations of alcoholics.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.