Interview: Eduardo Williams

Wandering, real and imaginary, physical and digital, has been a constant theme for Eduardo Williams. The Argentine filmmaker had hardly left his native country before journeying abroad to make movies after enrolling at the Universidad del Cine in Buenos Aires. Now, Williams treats travel as a personal and artistic quest. While his early shorts, Tan atentos (2011), Could See a Puma (2011) and The Sound of Stars Dazes Me (2012), were set solely in his home country, That I’m Falling? (2013) took him to Sierra Leone and I Forgot! (2014) to Vietnam. His first feature, The Human Surge, starts in Buenos Aires but quickly moves to the lackluster provinces, and then to Mozambique and the Philippines.

Wherever Williams goes, his protagonists turn out to be mostly young men and adolescents who come across as poetic drifters. In the melancholy The Sound of Stars Dazes Me, for example, they hang out in a no-man’s-land of abandoned ruins in rural Argentina. While the surrounding landscape may look enchanted, the boys’ preoccupations are mundane: gossiping about friends they have in common, taking photos of each other’s tattoos. One boy’s fainting incident sets off his two friends on a journey to fetch medication, but the result is more like Waiting for Godot: the walk is an end in itself, the resolution may never come. The boys’ lives are limited by their immediate environment, yet their world is also enlarged by their constant contact with the Internet, and by the unending stream of social media—a theme that is common to all of Williams’s work, and which recurs in The Human Surge.

Avoiding close-ups in favor of medium and wide shots, Williams invites his audience to think about his characters in terms of their surroundings. Often—as in a long sequence in The Human Surge—a young protagonist will wander the streets while the camera trails behind him at a distance, allowing us to take in deteriorated building facades and unlit graffitied underpasses. Just as often, we overhear intimate conversations but are unable to read facial expressions, either because of darkness or obstruction. This is perhaps because Williams is not interested in conventional plot development or psychology. He does not build tensions between protagonists, but rather accrues disparate stories with overlapping narrative threads.

The stretches of poetic dialogue that Williams interweaves with prosaic exchanges, and the seamlessness with which he moves between these two registers recalls the work of his Argentine compatriot, Matías Piñeiro. But the comparison ends there, for whereas Piñeiro delves into literary works, Williams favors disconnected anecdotes, urban legends, and snippets of random texts, at times gleaned from the Internet. There is no conscious hyper-textuality or “meta” game in Williams, maybe because he is not looking at the digital age as something alien, imposed or a metaphor, but rather as a new type of immersion.

In The Human Surge, the young man who finds himself jobless returns to his hometown, where his friends share his aimlessness. The young men make quick cash hiring themselves out for webcam sex, and through other sequences, Williams opens up a connection with youths in Mozambique, who are also broke, disaffected, and renting themselves out for cash. The transition to the Philippines is more arbitrary, fantastical—Williams follows an ant that burrows into an underground tunnel, in Mozambique, and then cuts to an anthill in the Philippines, as if that same ant emerged thousands of miles away. In Williams’s globetrotting film, relations are destabilized, quickly made and unmade, and the connection that the digital age touts remains a big unknown.

Film Comment spoke with Williams in August at the film’s premiere in the Locarno Film Festival about his exploration-driven process, the far-flung locations in his movies, and the odd lessons he learns from nature. The Human Surge screens October 9 in Projections (Program 11) in the 54th New York Film Festival.

I’m not sure I entirely understand the title, The Human Surge.

I know, it sounds a bit bombastic! But I think it works well with the film, which on one hand has a documentary feel, but on the other can be very poetic. And also very constructed. I mean “the surge” as in “a boom.” I don’t mean it as necessarily positive or negative. We don’t know if the human species is at its peak.

Technology is very present in your film and yet, ironically, we are often in places where it fails.

I am always connected but also always having trouble to connect. Internet seems to be everywhere, and yet it isn’t steady, so the film is about wanting to connect when it’s not possible. Technology is advancing and breaking at the same time. And then the same people who use it have to also work producing it.

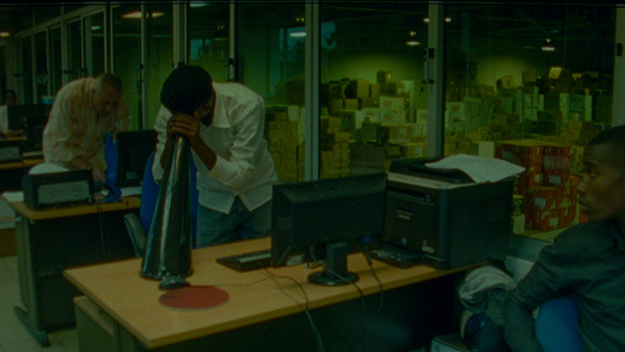

Is that why in the final scene we end up in a factory in the Philippines?

A factory where they produce tablets.

It is a pretty mysterious, frightening image.

Because people are working in this clinical, white, enclosed space, where the only thing that talks is a computer, saying, “Okay, okay.” The scene closes the film naturally. We saw people using technology and now they are producing it.

In the first part of the film, in Argentina, the dialogue is very fluid and conversational. How much of it was improvised?

In Argentina it is definitely more improvised, but it varies. Some of it is scripted. When I edit I mix the dialogue a lot and change its rhythm.

You rarely shoot in close-ups, which probably gives you a lot of freedom in post-production.

Exactly. But I avoid close-ups for another reason: to get the audience to see people as part of their environment, and also because the voice has a different function when it isn’t coming from a particular person. The way I film, your eye can roam a lot. You can focus on different parts of the frame. But then it is always hard to find a good still from my film, because it isn’t really made of close-ups, but rather of movement.

In the middle section, in Mozambique, the dialogue is very poetic.

That part is absolutely scripted. My idea was that the two boys escape from the city and arrive in a place that is a bit otherworldly. I wanted to add some mystery. There is the darkness. I liked this moment of estrangement.

Work, as well as joblessness, is quite important in your film.

Like any young person, I realized at one point that I would need to work for money. And it wasn’t as if you could work sometimes and then have time to explore. Normally, work occupies all your time. When I began traveling, I noticed that this preoccupation was the same for young people everywhere. Except, perhaps, when we are young, we don’t yet fully accept this fact. We have this illusion that the work we do is transitional. I find this self-perpetuating system absurd, but I approach it in a very experiential rather than an analytical way.

My characters feel a bit lost, but I think this kind of permission to be lost is also necessary to grow. People are so often afraid, but we need exploration to learn. In the Mozambique part, my protagonist gets to advance further, he has more freedom to go someplace new. We have a sensation of wandering and end up in a dark place and then he says that he must work for rich people to make money. It is also a question of how many people really work just to enrich others. And in the last section, in the Philippines, there is some pleasure, but then of course we end up in an industrial space—a somewhat pessimistic ending.

The connections that young people make in your film are very fragile, or fraught. In Argentina, they do it through online sex chat rooms. In the third part, in the Philippines, people spend the whole time looking for an internet connection, but the night comes and all cyber cafes close. We don’t get anywhere.

Those three distinct parts build on each other. If you get carried away by the movie, you also get carried away by this development, even if you don’t notice it.

So the permission to get lost is also the permission you gave yourself as filmmaker.

Of course, by writing a script that was only 15 pages and by not being afraid to go new places and discover things along the way.

What was it like for you to move from your earlier shorts to a feature?

After five shorts it felt natural. I always work with the same intensity, but I could add new elements. If you put certain strong things into a short, they will take too much attention from everything else. In a feature they blend in better.

What do you mean by “strong”?

Once I put a sexual element in a short, and then suddenly it seemed as if my main theme was sexuality. I prefer to keep things more diffused and to interrelate possible themes. I’m more interested in clusters that relate to each other.

Do you do casting calls for actors?

They are all nonprofessional actors. It changes a lot from country to country. In Mozambique, we did a casting call by putting up posters around the city. Some hundred people showed up. I contact some people via Facebook. In Argentina, my friends help me. Once we cast the actor in Argentina, we went to visit his neighborhood, places he liked. I discover locations with my crew separately, but at first I just spend time together with the actor to understand each other without having to explain too much. I think I achieved this in Mozambique and in the Philippines as well. You need this kind of energy and the permission for actors to invent, which adds another layer to the film.

You knew your locations before?

No. I wanted to arrive in a new place, so that the idea of discovery would be reflected in the film. In Mozambique, I had one month to explore and another two weeks to shoot.

But how do you then select which countries to visit?

I knew I wanted to go to some part of Africa, which was quite general, but I had made a film in Sierra Leone before [That I’m Falling? 2013]. Eventually, we found local producers who could help us in Mozambique. Other times I find locations on Google.

Some filmmakers are hesitant to dive into a new cultural context, but in your case it becomes your method.

I just find it exciting. Before I turned 23, I had traveled very little. I started traveling because of the short films, and found that I was very attracted to listening to people in different languages. Or even in Spanish, when words are being invented or spoken incorrectly. In the film, I really use the language as it is being spoken. Some of the best lines come from the people in it.

You also mix reality and fantasy through juxtaposing daily life and strange stories. All those bizarre little stories, such as the one about cockroaches. Do you collect these sayings along the way?

Some sayings I collect from the Internet, from Twitter or Facebook. Others are things that people have said to me or actual things that have happened and then I ask my actors to re-create them. I welcome this kind of invention in the film.

How did you shoot the film? The colors in the middle part in Mozambique are striking, even garish.

The Mozambique part may be the strangest one visually. I shot it with a Blackmagic Pocket, a small video camera that looks almost like a photo camera. It’s great for shooting in the street, it almost makes you pass for a tourist. Then I reshot everything in Super 16 off my computer monitor, to create that feeling of looking at images on a computer. Because that’s what my characters are doing. In Argentina, I shot in Super 16 and in the Philippines on video.

So the color distortion is a result of looking at the computer screen.

Yes, it gives you a rough effect. The last part was shot with a big video camera, RED Scarlet. I had shot some of my shorts on 16mm as well.

What do you like about 16mm in particular? Jonas Mekas talks about how it’s intimate and pre-video.

I use it as an amateur video camera but with a texture that is more cinema-like, less YouTube video. In The Human Surge, I mix formats, because of the shooting limits that each camera gives you. In 16mm you end up having less material, which means constraints that require you to shoot in a certain way. Video gives you more freedom, whereas a small camera allows you to work in the streets without being noticed. I like to see how these different limitations and textures affect my work. Before, in Sierra Leone, for example, I shot with a big video camera, which was quite tiring for my crew. Then in Vietnam, for I Forgot!, I wanted to use a light camera to have more flexibility. A small camera also seems more natural to young people, so they don’t become as camera shy.

What was the editing process for The Human Surge?

I first shot each part and then edited it myself before shooting again, just to see if my idea for the film changed. For the Philippines part, for example, I decided to change my character from a boy to a girl. I wanted to change the sensibility, the body movement and voice. At the end, I went back to Argentina to reshoot some scenes and then I worked with an outside editor for three weeks.

And is the sound mostly diegetic?

I try to register as much sound on location as possible, because it is very important to have diegetic sound. But then I work on it a lot in postproduction. In nature scenes, I invent certain digital sounds to enhance the ambiance. We bring back at the end certain sounds that are present in the beginning, though the audience might not necessarily notice. The sounds are not very distinct, but I like this development, coming back at the end. The same thing happens in the film, I think, the way images accumulate in your mind and repeat themselves. They resonate with each other. Some sounds from Argentina come back in the Philippines. But of course sound also helps to distinguish places.

So there is a progression in the sound design, but also a circular motion.

A kind of magical sound, overlaying fantasies over the documentary ambiance, which helps to create a special atmosphere. That’s the great thing about sound—images affect us in a more conscious way, but sound is more mysterious.

You often pick very unusual, even foreboding, locations: the deep underground tunnel in That I’m Falling?, the hollow insides of tree trunks…

I want to have an element of surprise. The places I pick are magical yet concrete. They also change your point of view, like the moment when the boys climb to a high place in my short, I Forgot! It’s a place I saw on the Internet. You can trace it on the GPS, so that’s how my idea started.

Now that I think of it, my relationship to technology is mostly reflected not in the story itself, in the moments when someone is looking for Wi-Fi and so on, but rather in the structure of my story and in how I switch from place to place.

Kind of like Internet surfing?

Of course, because my brain and practice have been transformed by technology. For example, by the video games that I played when I was young. In video games, you have these different levels that you advance to, moving through multiple spaces. And then the chats—at many points in my life, it seemed like online chatting was my only means of communication. It is a different way of speaking, of connecting. I didn’t think of it at first, but this is why I structure my films the way I do. It’s about how I see and relate to the world.

Your first encounters are virtual?

That’s how I meet and connect with actors sometimes. People who I only then meet in real life.

A virtual network. A real Facebook generation.

In my adolescence everything had to with computers and games and virtual spaces.

But even though we experience the world through a computer and transition from Argentina to Africa with its help, there is a different, organic transition in the scene with the ants. Are they a metaphor for work?

But I read some place that certain ants actually have no function. They are not doing any particular work!

Ants are more idle than we think?

Yes! [Laughs] They are just there, in case something happens. I discovered that observing ants and nature was another way of communicating, or perhaps traveling to another point of view, or trying to understand movement. Even if your knowledge is not scientific, it is another form of life. Maybe it’s even better to just observe and discover first, with less information. Experiencing things through shapes and sounds, which is a form of pleasure. We are living in a world that is always feeding us words, and in which we are always thinking in phrases. But thinking can also come through movement. It can be more experiential.

Ela Bittencourt works as a critic and curator in the U.S. and Brazil and is a member of the selection committee for It’s All True International Documentary Film Festival in São Paulo.