Interview: Dominik Graf on Melting Ink

This article appeared in the November 16, 2023 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

In his 2020 book Jeder schreibt für sich allein (Everyone Writes for Themselves), Anatol Regnier traces the lives of prominent authors who chose to continue working in Germany during the Nazi era. Regnier tells their stories chronologically from 1933 up to the immediate postwar years, in the process revealing the various ways in which artists compromised their principles, became reconciled to their fates, and in many cases openly collaborated with the Nazi regime.

Best-selling author Hans Fallada, for example, accepted a request from the Ministry of Propaganda in 1943 to write an anti-Semitic novel; the request was, in Fallada’s words, “as generous as it is honorable” (though his guilt was a likely factor in his later alcoholism and institutionalization). The revered expressionist poet Gottfried Benn enthusiastically supported the rise of National Socialism and vowed his allegiance to Hitler in 1933, before becoming disillusioned with the Nazi party and, subsequently, being banned from further writing by the National Socialist authors’ association.

For German filmmaker Dominik Graf, among the most significant revelations in Regnier’s work is that beloved children’s-book author and novelist Erich Kästner wrote film scripts commissioned by Joseph Goebbels, contradicting the writer’s public claims that he was unable to find work during the 12 years of Nazi rule. In 2021, Graf adapted Kästner’s 1931 novel, Fabian: The Story of a Moralist, finding in Kästner’s late-Weimar-Republic Berlin a site of manic energy and ill-fated romance, with resonances in 21st-century Germany.

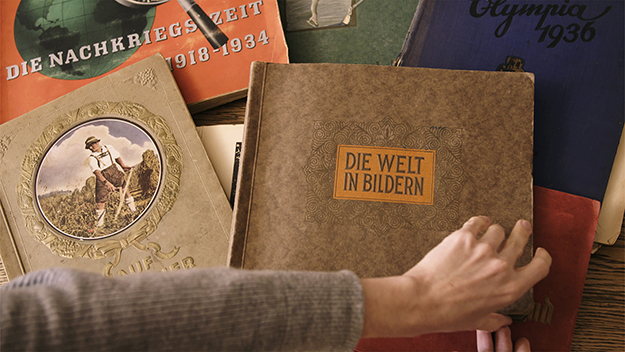

Graf’s latest documentary, Melting Ink, which premiered at the Berlin Critics’ Week last February and is as yet undistributed in the U.S., takes Regnier’s research as a starting point for a wide-ranging analysis of those parts of the human psyche that justify and then repress our most beastly behaviors. Best known in Germany as a director of police procedurals, Graf has had a long and varied career, alternating among television work, narrative features, and documentaries. (Only two of the more than 50 projects he has directed have received U.S. distribution—Fabian: Going to the Dogs and his 2014 Friedrich Schiller biopic, Beloved Sisters.) At nearly three hours, Melting Ink illustrates Graf’s voracious curiosity and formal dexterity, jumping from archival footage to conversations with Regnier to staged re-creations and talking-head interviews with historians and prominent German cultural figures.

Melting Ink begins and ends with the story of Douglas Kelley, an American psychiatrist who concluded that, according to the best diagnostic tools of the day, many of the defendants at Nuremberg were in fact perfectly well-adjusted people. For Graf, this mystery is a timeless concern, illuminating both the impossible decisions faced by artists under Nazi rule and the “dangerously simple” moral language of our current public debates that threatens to erase all context and complexity.

I spoke with Graf before the premiere of Melting Ink at the Berlin Critics’ Week earlier this year.

Did Regnier’s book cause a sensation in Germany?

No. Complete silence. There were a few reviews in the beginning that said, “Didn’t we know this already?” I had read it while he was working on it, and I had never read something like this before. But it was underplayed somehow. And then, after a year or so, there started to be serious reviews in the big newspapers. So slowly, it became famous. But it still doesn’t have the respect that it should have had from the beginning.

The opening section of Melting Ink includes several scenes in which interviewees describe what a “gut punch” it was to discover that artists they revered had made such compromises. Of the writers you profile in the film, are any of special importance to you?

Erich Kästner. I actually met Kästner when I was 10. I won a reading award in Munich, and he was on the jury. My mother knew him, and she jumped up to greet him. She was always keen on famous people. He looked at me—he was as small as I was at that time, big red nose—and I think he wasn’t very happy. But he was nice. I liked him. He had something humorous—always humorous, and also serious.

But it’s not only that. I read Fabian when everybody in my generation read it in the ’70s, because the book transports the ’20s into the ’70s. I loved that book from the beginning, but mostly the love story. That is the reason why the love story appears very prominently in [Graf’s adaptation of Fabian], as well as in the small scene [in Melting Ink].

You’re referring to the brief sequence in Melting Ink where we see Tom Schilling and Saskia Rosendahl as their characters in Fabian: Going to the Dogs. What exactly are we looking at in that scene? Is it a rehearsal?

The two actors were not on set at the same time. They came on different days, and I was always the counterpart. It’s a wonderful dialogue, but it didn’t make it into the final script. As a get-to-know-each-other dialogue I found it very, very beautiful. I always regretted losing it.

It’s an important moment in Melting Ink because like so many of the people you interview, you’re unapologetic about your admiration for the art. Rosendahl’s character Cornelia tells Schilling’s Fabian he is “infected by the misery of the world,” and you respond in voiceover, “Who had ever written such beautiful dialogue in German?”

Yeah, that’s my real opinion.

Much of your career has been in television and genre film, but Melting Ink is, I believe, your ninth documentary?

I started making documentaries—well, more essays than documentaries—with Michael Althen, the famous film critic here in Germany who died in 2011. We did a film together about my father [A Whispering in the Mountain of Things, 1997], because he somehow liked my father as an actor in the ’60s. I was a bit pushed into this kind of work, but then I found it extremely interesting. Documentary opened a panorama of possibilities: how to tell stories, how to analyze, how to go into new subjects that interest me.

There was a very important moment in the film about my father when I had planned to ask all the people that I was interviewing, “Did you talk about the war?” And since I knew my father didn’t like to talk about it, I had assumed they would say, “No, of course not.” But the first person I asked said, “Oh, yes, yes, yes.” And then something interesting happened. Suddenly, he paused and said, “Oh, no. Not so often. We didn’t talk at all.” And this change? That was wondrous.

I was astonished that Anatol’s book interested me so much because I never wanted to make a film about the Second World War. But then, in this kind of strange telling, Anatol portrays the fate of nearly 100 writers, an unbelievable number of people, from 1933 to 1948. Writers in crisis, one after the other.

You frame the film with the story of the psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who analyzed the Nuremberg defendants using Rorschach tests. We can talk more about Kelley, but I wonder if you find Freud useful as an analytical tool?

I’m still more Freudian. I don’t know if I would ever believe in the truth of the Rorschach test, but Freud has very simple answers to complicated problems sometimes. And some of his answers are ingenious, I would say.

Often in Melting Ink you and your interviewees wrestle with the idea of the “inner emigrant,” a term the writer Frank Thiess coined to rationalize his decision to stay in Germany and continue writing novels in a style that gave no offense to Nazi censors. I can’t imagine the terror, guilt, and shame one would have to repress in order to simply function under those circumstance.

Of course. After the Second World War there was a lot of what Freud called Verdrängung, meaning “pushing the memory away.” All the people that I spoke with in the film about my father, when I asked about the Second World War, made the same gesture. [Makes a pushing motion with both hands.] This is really Verdrängung—pushing it away, putting it into a dark corner and never wanting to see it again.

In your film, historian and critic Julia Voss has little sympathy for the artists who compromised their principles, and is hostile toward figures like Benn, who was later rehabilitated into, in her words, an “apolitical” figure worthy of being memorialized on a German stamp. Do you have a sense that, in hindsight, any of these authors wished they had done things differently?

Yes, I found it interesting that Voss, who is younger than me, has such a strict view on things. She expects these dead poets to have regrets—to say, “Well, I made a mistake,” or “I should have done it differently.” I would never think that. My goal was to show the character structure of these people, women and men equally, and how they fell into a trap that they built for themselves. They fell into their own trap. Gottfried Benn, for instance, thought fascism was great, a new Nietzschean people being born. What a stupid thing to say. But he uses very, very—when you read it in German—beautiful language to show his enthusiasm for this new generation.

I can’t imagine asking Benn after the war, “Don’t you regret it?” I don’t believe it. In the ’50s Benn said something like, “The art lives forever. And the art is worth every crime.”

Melting Ink cuts from interviews to archival photos to found footage to staged re-creations. Is that typical of your documentary style?

Everything that is useful, take it. I always try to have a consequential style, but in this case, the consequence is to be hedonistic, to choose everything—everything that comes my way, that I find interesting, and that I want to show to the spectator. Quick, quick montage. Sometimes slower music. Whatever comes to mind.

The film ends with an epilogue that compares fascism to a virus—always mutating to adapt to present conditions. I like this bit: “We cannot deal with our own inherent contradictions. Instead, we repress and we judge. We speak of our ‘values’ to feel secure.”

With hindsight, we make everything too simple. And at the moment, it seems dangerously simple. Good. Bad. Guilty. Not guilty. These kinds of easy-to-make distinctions that, in the end, teach us nothing. That was one of the reasons I made this film. Of course you could say, “I don’t want to meet Gottfried Benn. He seems to be pretty awful.” But he’s a great poet.

The shades of gray inside these personalities make them useful examples. And when you follow these examples, then you find different ways to cope, different strategies, including strategies to lie to yourself. But you also find something that is much more complicated than simple answers. That is also why I use this story of the Rorschach tests of the Nazi leaders. These are not beasts. They were normal people, and that is the most scary thing about it. We are all pretty normal, but what comes out of this normality in certain situations is still a mystery.

Darren Hughes is a freelance critic and artistic director of Film Fest Knox in Knoxville, Tennessee.