Film of the Week: The Future Perfect

The ideal viewer of The Future Perfect, best placed to pick up all the nuances of its dialogue, would be a fluent speaker of both Mandarin and Argentinian-accented Spanish. For the rest of us, Nele Wohlatz’s concise but rich comedy is one of those films in which subtitles truly come into their own. In one scene, heroine Xiaobin (Xiaobin Zhang) finally opens up and tells her suitor Vijay exactly what’s on her mind: “I don’t know if you’re the person you say you are.” But they’re used to conversing somewhat haltingly in Spanish, and on this occasion she’s speaking in her native Mandarin, of which Vijay doesn’t understand a word.

It’s one of the few moments in the film when Xiaobin is fully in command of the language she’s using, and now it’s the non-speakers of Mandarin among the audience who are at a disadvantage, along with Vijay. For much of The Future Perfect, Xiaobin is doggedly flailing with her Spanish—although by the end, she’s doing admirably. She’s doing so well, in fact, that she’s able to carve out a new imagined life, or lives, for herself in her head. Among other things, The Future Perfect is a great advertisement for language learning: stick with those tricky tenses, it tells us, and eventually everything becomes possible.

The Future Perfect—pleasingly compact at 65 minutes and the winner of the Swatch First Feature prize in Locarno last year—is the work of Nele Wohlatz, a German filmmaker working in Argentina. Wohlatz may conceivably be drawing on her own experience of language learning, and of feeling foreign, although arguably Latin America lies at a greater cultural and linguistic distance from China than from Germany. Still, Wohlatz offers a perceptive, empathetic, very tender picture of how it might feel to be an 18-year-old Chinese woman arriving in Buenos Aires and working to carve out a new independent life and identity.

When we first meet Xiaobin, in the language class she attends, she knows enough Spanish to answer simple questions from her off-screen teacher about her family—parents she hasn’t seen for years, and younger siblings that she’s only just met. The first important thing she did on arrival, she explains, was to go to her uncle’s supermarket, where she had a job at the meat counter, and to learn the names of the cold cuts. Another Chinese girl puts her through the basics—lomito, salame, mortadella—but Xiaobin’s inability to grasp questions of quantity, or the difference between jamón crudo and jamón cocido, shows she has a long way to go. So does a melancholy episode in a café where she can’t order anything, as the only Argentinian dish she knows is barbecue, which isn’t on the menu.

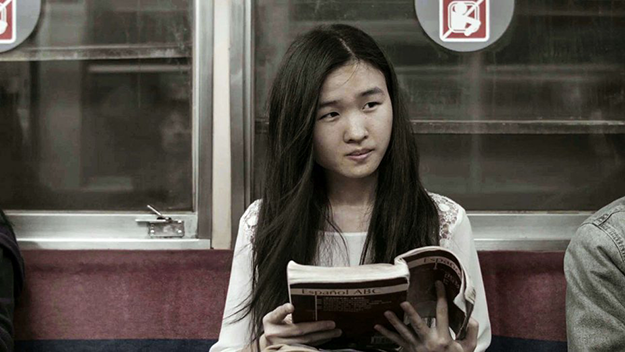

Still Xiaobin and a group of other Chinese students persevere, applying themselves to the role-playing at the language class. She is assigned the provisional identity of Beatriz, a Spanish nurse, and uses the name as she goes about her daily business (a friendly optician later suggests she might prefer “Sabrina,” which sounds more like Xiaobin). On the themes of names and identity, the film sets off on a teasingly philosophical tack: after a number of classroom exercises about imaginary characters and their jobs, we see a montage of passengers on the subway, and are immediately tempted to classify them accordingly: which one’s a waiter, we wonder, which one a businesswoman?

As the film goes on, Xiaobin/Beatriz and her fellow students master various basic tools of Spanish, and find their world and possibilities of expression expanding accordingly. “It would be nice to have a cat at home,” muses a girl, “so as not to be lonely.” Beatriz replies with a glimpse of her own truth, by now capable of real candor: “I have to take care of myself. I don’t want to take care of a cat.” Even before that, simple words speak volumes. Asked about the first Spanish words she ever used, Xiaobin replies, “Jamón y queso” (ham and cheese). Asked what she likes to eat, she replies, “I like to eat Chinese food.”

Xiaobin’s story might easily have lent itself to a sloppily feel-good, quasi-realistic treatment; heaven forbid a Hollywood remake in which a pupil in an English class triumphs as she acquires the verb forms and the cultural values that accompany them. But, while it has a satisfying emotional thrust, The Future Perfect is a highly thoughtful, even theoretical film, and is executed accordingly. The acting, almost entirely by newcomers—although there’s a brief self-reflexive interlude featuring Argentinian actor Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, soon to be seen in Robin Campillo’s BPM (Beats Per Minute)—is pretty much uninflected, as the nervous students struggle to master their basic words and grammar. What we notice, therefore, is the difference between the flatness of their Spanish diction and the inflections which are so crucial in Chinese, in which the same words have different meanings depending on how they’re spoken. So Xiaobin’s story is a search for nuance and semantic possibility, as well as for emotional self-expression.

The matter-of-factness of the acting, as well as of the directing style, foregrounds this struggle wonderfully. That’s especially apparent in Xiaobin’s scenes with Vijay (Saroj Kumar Malik), an awkward, rather older Indian man who approaches her in the supermarket, promptly asks her if she’s on Facebook—another device for classifying individuals’ identity—and before long is pursuing her. They appear to spark—or at least, to be acting out scenes about a couple sparking, because they don’t have the linguistic wherewithal to express complex feelings. Even when he says he wants to marry her—“I want to be with you forever”—Vijay seems to be reciting a phrase from a textbook. Everyone here is simply using the available words, but aren’t yet comfortable enough in Spanish to make them signify.

In the meantime, it feels as if Xiaobin and Vijay are performing exercises; that’s never more apparent than when they go back to the no-barbecue café and order orange juice. “Shall we go?” Xiaobin asks, and they leave, the juices remaining barely touched on the table. Their intimate moment together might as well be a rudimentary sketch entitled “Xiaobin and Vijay Order an Orange Juice.” Wohlatz directs accordingly, in a seemingly functional style, the actors largely performing in an uninflected manner that feels a touch Bressonian, although it’s perhaps closer to the deadpan of Aki Kaurismäki or Eugène Green. The film has the deliberately pared-down look of a low-budget piece foregrounding its budgetary limitations; it tends to privilege simple, static shots, especially in the classroom. But Wohlatz and DPs Roman Kasseroller and Agustina San Martín also free things up in the exteriors, as Xiaobin wanders through the unfamiliar city or returns home to the laundry run by her mother (who is usually heard off-screen and only glimpsed in one scene). In one night shot, the camera drifts up from the street to catch Xiaobin silhouetted in an upstairs window, looking out on the street: a poignant visual consolidation of her loneliness and urge to escape, which she has already, knowingly or otherwise, signaled in her basic Spanish.

The film’s title refers to the future perfect tense, as in “I will have ordered orange juice”—but it could also mean “the perfect future,” which Xiaobin dreams about. We don’t see her class specifically learning the future perfect, but it does get to grips with the conditional, a tense which allows us—as a textbook specifies—to imagine alternative futures. In reply to her teacher’s questions, she lets her imagination run wild and conjures up a range of possibilities—sad, comic, downright bizarre—of how her relationship with Vijay might go, and how her life might end up. Xiaobin doesn’t quite get a grip of the grammar, and keeps lapsing back into the present tense, but that only makes her imaginings more real and immediate—making, in one abrupt change of location, for what, in that Hollywood remake, would be our neat, feel-good ending. That’s not quite the payoff that Wohlatz gives us, although we’re welcome to hold onto the hypothetical warm glow, if we prefer; instead, a tartly enigmatic coda suggests in one neat image that language itself can be a tool and a cage, and that sometimes there might be something to be said for having a cat to look after.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.