Film of the Week: Horse Money

Writing about Pedro Costa’s Horse Money in the current issue of Film Comment, Kent Jones argues that the Portuguese director’s films “have been more lauded than described.” There may be a reason for this—the difficulty of describing these increasingly complex and elusive objects. In a recent article, Mark Peranson nevertheless makes a case for the necessity of such description: “the most true-to-form analysis of Horse Money should proceed in this painstaking way, shot after shot, because to examine the film as a whole, or as a connection of scenes that flow one into the other, is an impossibility. (Every review of this film is guaranteed to get at least one detail wrong; after seeing it three times the film remains intangible to me.)” One reason for this intangibility, Peranson suggests, is that, “like Jean-Marie Straub, Costa adheres to the philosophical impossibility of matching one shot to the next.”

Whether or not shots fit with each other in Horse Money, sequences barely seem to match sequences: this is a film of formidable discontinuity that takes the form of a dream. Which is not to say that Horse Money represents a dream, simply that it uses the fragmentation and hidden chains of connection that are peculiar to dream logic. The film is all the more perplexing in that it appears, on the surface, to be nothing new: depicting and starring Cape Verdean immigrants, some of them residents of the now-demolished slum area of Fontainhas in Lisbon, Horse Money appears to be a continuation of, even a sequel to, Costa’s 2006 film Colossal Youth, also about members of that community. Between the two films, Costa made a number of shorts that are, thematically and formally, in some ways of a piece with the two (among them, Tarrafal, 07, and Our Man, 12).

At first viewing, I was bowled over by the poetic authority of Horse Money, but a little disappointed that it didn’t seem at first to be much of a stylistic advance on Colossal Youth, returning to that film’s tableau-like compositions and incantatory poetic dialogue (whereas that film was very different in style from Costa’s previous studies of working-class Lisbon, Ossos and In Vanda’s Room). However, a second viewing confirms the richness of Horse Money, and makes it clearer to me that it is a very different film to Colossal Youth: a nocturnal, oneiric leaf in a diptych, complementing that film’s fundamental rootedness in daylight realities.

The film’s puzzling character begins with its English title—don’t expect a bustling racetrack drama. The Portuguese title is Cavalo Dinheiro, dinheiro meaning “money” as well as a former currency. The title could be taken to mean “A Horse Named Money,” or “Money’s a Horse,” just as González Iñárritu’s Amores Perros (in other words, “loves that are dogs”) can be translated as “Love’s a Bitch.” But “Dinheiro” is also a horse. In one sequence, the elderly laborer Ventura—a nonprofessional screen presence who has become Costa’s acteur fétiche, or given his monolithic grandeur, perhaps his acteur totème—meets a woman named Vitalina (Vitalina Varela), a more recent arrival from the former Portuguese colony of Cape Verde. He asks her for news of the land which, given what the film tells us about Ventura’s chronology, he left behind long ago, at least as far back as the Seventies. He asks about his old house. “Not a stone left standing,” Vitalina says. What about his donkey, Fogo Serra? “Dead.” And his horse, Dinheiro? “The vultures tore him to pieces.”

Dinheiro’s presence in the title highlights a central theme of the film: loss (especially of a violent nature) and the awareness that you can never go home again. Horse Money is about two losses experienced by Ventura and his peers, that of their former homeland, and of Fontainhas, a grim place to live, yet the center of a community that embodied a strong exile identity. Colossal Youth was partly about the attempt to sustain that community after it was transplanted to modern high-rise estates; few visual artists have been as successful as Costa was in that film at imparting a new poetic, even mythic visual signature to seemingly soulless brutalist architecture.

There’s one further horse reference in the film: a moment at which Ventura encounters a younger man named Benvindo, his nephew or godson, in a deserted factory. Together, the two men chant an a capella lamentation that begins, “I scream like a horse…”, before stopping to argue about the words. Rather than a cri de coeur, then, Costa’s film might be described as a cri de cheval, an extended horse scream: in a sequence showing a number of statues around Lisbon, I don’t believe there is actually an equestrian one, but the references to horses, and the prevalence of sculpture, brought to mind—by a not entirely unjustified process of association—the image of classical statuary’s neighing horses in marble, screams frozen in noble, timeless immobility. That’s the tone that characterizes Horse Money: one combining the agonized extremity of nightmare with the detachment also peculiar to dream. Contradictory as it sounds, this distinctive tone is a hell of a way to contemplate the real.

So, to attempt to describe Horse Money: it is the proverbial journey to the end of night. The traveler in question is Ventura, the elderly worker and community patriarch who was at the center of Colossal Youth. After a series of mainly black-and-white stills—Jacob Riis’s fin de siècle photographs of New York slum life—and then a formal oil portrait of an unidentified black man, the camera pans right to a dark staircase leading down to an iron gate, and apparently the bowels of the earth. For much of the film, we’re down there in the dark with Ventura, in what resembles a vast network of cloisters and tunnels. Perhaps we’re in the chambers of Ventura’s memory or hallucinating mind, where the film is arguably set. Yet, on a semi-realist level, the principal setting appears to be a strangely deserted hospital, where Ventura is being treated—for wounds received during a fight years before, or for some sort of nervous condition in the present, or both.

For much of the film, Ventura remains underground, or in hospital; he variously wanders around, stops to be conversed with in cramped examining rooms, or lies in bed receiving a visit from other Cape Verdeans who may be friends, hallucinations, or ghosts from the past. These characters’ precise nature is obscured by the fact that, like Ventura himself, the actors are nonprofessionals, apparently using their own names in the credits; to what degree they are either playing themselves or embodying imaginary versions of themselves remains hard to pin down.

At any rate, we learn that one visitor, Delgado, set his house on fire with his family inside, and never spoke again; Benvindo fell from the third floor of a construction site; Lento sold drugs to supplement his laborer’s income, and got hooked. One of the company remarks, with bleak fatalism, “We’ll keep on falling from the third floor… We’ll keep being severed by the machines… We always lived and died this way.” The bitter reality of industrial accidents, and of workers unprotected by the callous powers that be, is a political refrain that runs through the film. Later, Ventura—whose own insistently trembling hand may be a result of industrial damage, or just the wear of a life’s debilitating labor—visits a now abandoned factory where he once worked. There Benvindo tells him of a man ground to death there by a malfunctioning machine. It won’t happen again, though; the factory owner ran away with the company’s money, and its machines. We get a sense of Portugal itself as a ghost country, or a once-thriving enterprise now closed for business.

The discontinuity is unsettling. Ventura passes through the film changing his clothes constantly: sometimes in pajamas, sometimes in frilled shirt and red trousers, or only in flat cap, boots, and red underpants. Passages and elevators sometimes lead him from one place to another with apparent logic, as if the corridors of a modern hospital could plausibly be connected to underground cloisters; at other times, he seems to teleport, at one moment confronted in the nocturnal city streets by soldiers and a tank (his quivering hand the only thing that moves in this startling, rather Goya-like tableau vivant), the next waking up on the ground outside the empty factory.

Reality remains indeterminate; sometimes Ventura is manifestly the elderly man we see, at others he still seems to be living out his own past. Early on, he announces, “I am 19 and three months”—then identifies himself as “bricklayer, retired” (he also identifies himself both as Ventura, which is how he’s credited as a performer, and as José Tavares Borges). Later, the dialogue depicts him as a young man yet to build himself a shack in Portugal, or to bring his wife Zulmina to join him. He is told by the ghostly statue of a soldier: “All your children are yet to be born.” But the same figure also tells him: “You’ve died a thousand deaths, Ventura—what’s one more?” The Cape Verdean Everyman, or every poor person who ever was, Ventura is shown living every moment of his life at once, all the glory and all the squalor simultaneously.

The living statue appears in a 21-minute sequence previously featured in slightly shorter stand-alone form as “Sweet Exorcism,” a chapter in the 2012 portmanteau film Centro Historico (alongside episodes by Aki Kaurismäki, Manoel de Oliveira, and Victor Erice). This sequence is haunted—in the figure of the metallic-painted soldier, who appears in different postures from shot to shot, but never budges and never moves his lips—by the Carnation Revolution of 1974, which overthrew a right-wing dictatorship that had been in place since the Thirties. The Revolution was famously peaceful—hence the name it’s remembered by—yet the soldier’s words constantly evoke the violence of revolution. It’s suggested that for Portugal’s Cape Verdeans, disadvantaged outsiders, the revolution was as terrifying as it was joyous for others. Another date referred to—the moment Ventura incurred his wounds—is March 11, 1975, the day of an abortive right-wing coup. The hallucinatory extended sequence in the lift arguably immobilizes the film for longer than is comfortable, and a violent blast of organ from a Messiaen piece is an incongruously dramatic flourish; but the episode is an object lesson in how to film two figures in an enclosed space for a long period. It’s also the point at which the film’s sound design is at its most hallucinatory, a host of disembodied voices taunting Ventura and filling every inch of this cramped area as they do his ears.

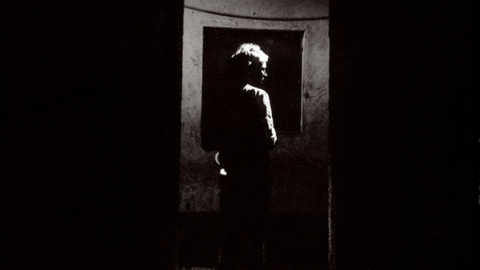

The other figure that dominates the film—its active, powerful force, where Ventura is oddly passive, even semi-absent—is Vitalina Varela, who has a quasi-supernatural presence of her own. She’s seen dressed in black leather against a black exterior, a cityscape dotted with little squares of lit-up window that seem more like square holes punched in the wall of a dark chamber; or she’s framed against an illuminated white screen, emphasizing the blackness of her skin and the gauntness of her features. She arranges necklaces in shapes on a table, an enigmatic ritual that, by all accounts, Varela launched into unprompted. All the time, she whispers eerily, her incantations contrasting with Ventura’s more sing-song poetic delivery; as she reads out official documents relating to death, birth, and marriage, she brings alive the hidden poetry of bureaucratic language, once detected by the Surrealists, but also its incapacity to account for the lives and deaths it records.

Complementary to Colossal Youth, Horse Money is in some ways its diametrical opposite: where the former used light, blocks of whiteness, forms redolent of heroic classicism, Horse Money is nocturnal, steeped in sinister chiaroscuro, Romantic. Shooting in boxy Academy ratio, Costa and co-DP Leonardo Simoes use diagonals and heightened perspective in a similar fashion, but here to intensely claustrophobic effect, deep-focus corridors shooting into the distance, rooms seeming to close in on people, while the few outside shots feel like interiors (the penultimate shot, with a patch of red sky behind a black building, suggests an Expressionist stage set). Patches of light in darkened rooms seem to have been slashed out of the space with a straight-edge razor. This is a film buzzing with echoes of art history: an Edward Hopper office, corridors like Piranesi’s prisons, night shots in a wood in which foliage and rock have textures reminiscent of Salvator Rosa’s Baroque landscapes. It’s rare to see a film this haunting and this haunted; rarer still that such a film should be deeply and specifically inspired by a current social and economic reality. Horse Money is an inspired reminder that politically rooted cinema needn’t just inhabit the realm of the strictly real; it can have an unconscious too, a dream dimension haunted by ghosts.