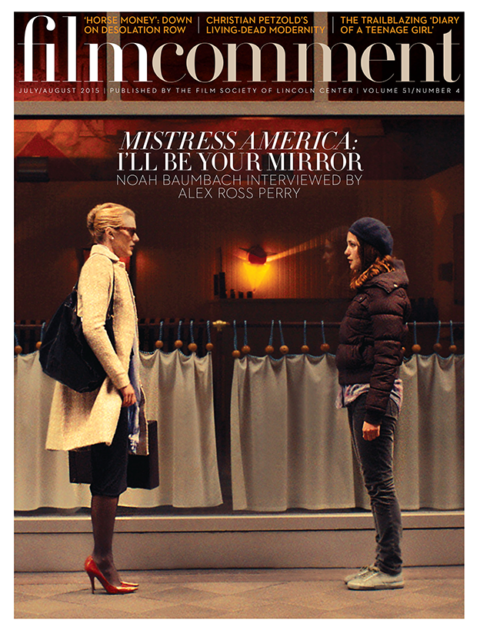

By Kent Jones in the July-August 2015 Issue

The Turning of the Earth

In his mesmerizing trance film Horse Money, Pedro Costa stays true to common humanity

The demonizing rhetorics of the various international ‘wars’ on terrorism, drugs, and crime are so much semantic apartheid,” writes Mike Davis in Planet of Slums. “They construct epistemological walls around gecekondus, favelas, and chawls that disable any honest debate about the daily violence of economic exclusion.” One might enlarge on Davis’s statement by evoking the tacit collective understanding of the condition of the poor, embodied in the gentler but no less exclusionary rhetoric of op-ed pieces and radio chat shows, no matter what the political stripe. There is never a “we,” but always an “us” and a “them,” and “they” are heard from when a statistic needs fleshing out or when a “good story” (usually a narrative of redemption) or a compelling “character” has been identified.

From the July-August 2015 Issue

Also in this issue

This kind of stuff is, I suppose, inadmissible to Pedro Costa, for whom common humanity isn’t a question but a fact—not something to worry about or to proclaim allegiance to, only something to enact. I suspect that for Costa, the greatest concern is how to keep his films at ground level, one-to-one with Ventura—Costa’s Henry Fonda and Francis Ford rolled into one—and the other friends he made in Fontainhas, a now demolished “improvised” Lisbon neighborhood of Cape Verdean immigrants. Not that this filmmaker seems unaware of his place in a world where the division between rich and poor seems to be ever expanding and widely accepted as a sad but necessary condition of existence.

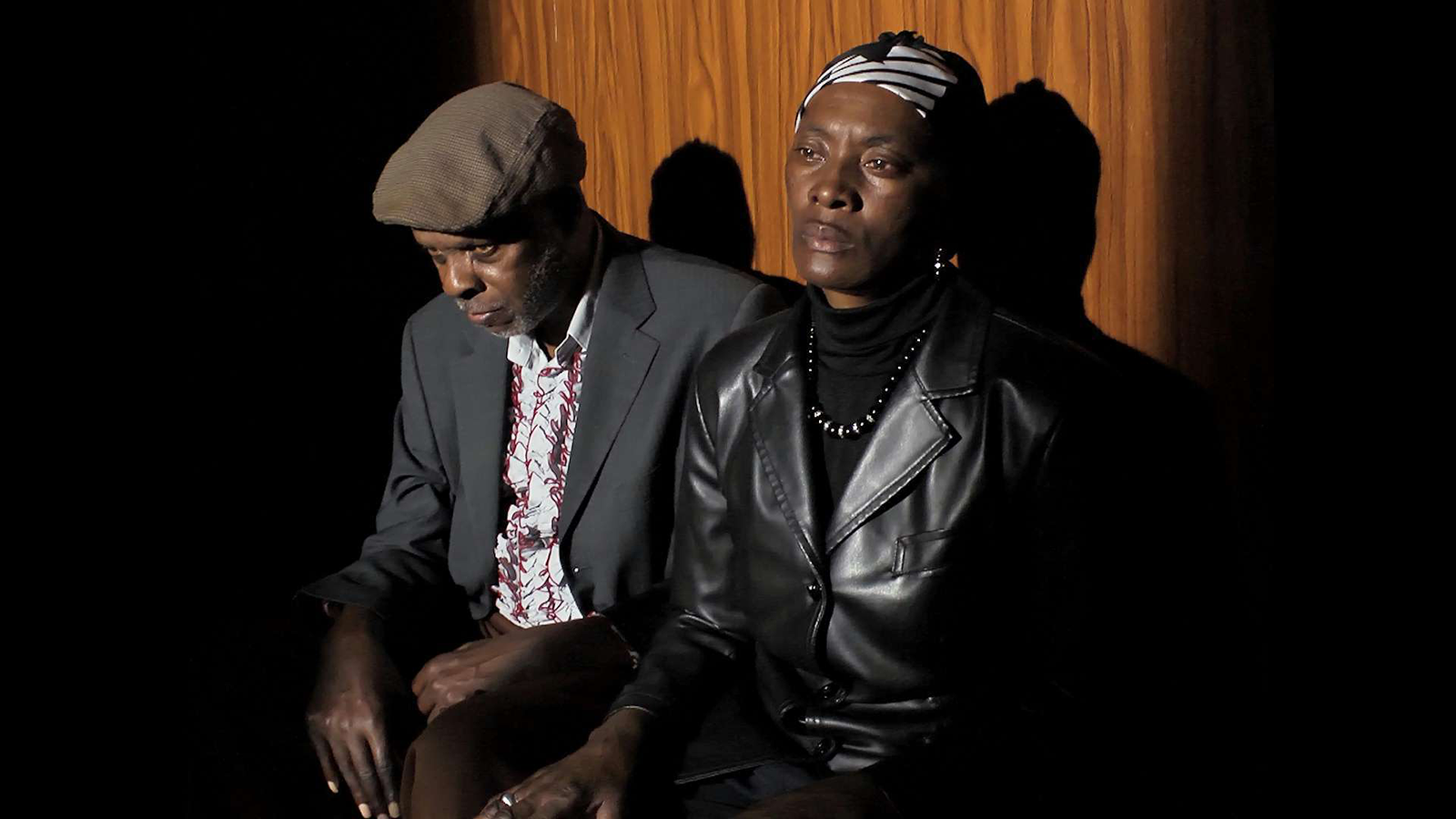

Costa has been embraced by a few, perhaps a little too fulsomely in certain cases—it must be said that the films have been more lauded than described. He has also been condemned with charges of aestheticism: how dare he frame Ventura like Woody Strode, bathe all of these impoverished men and women in luxurious shadows, and pin them in static compositions as they recite his formalized texts? Moreover, he has been granted charter membership in the dreaded consumer category known as “slow cinema,” as unproductive a critical invention as all of the above-mentioned stuff about exploitation and the glorification of poverty.

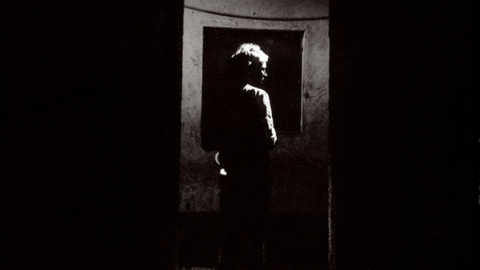

I think that each of these supposedly cutting-edge issues is handily nullified by the mesmeric power of the films themselves, far richer and more elusive than one might guess from the critical literature. Costa has long had a dream of adapting Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions album as a film, and it seems to me that he layers and structures and sequences his films like a musician in the studio. Every aesthetic choice is lovingly tuned, from the particular sound of a given space’s quiet to the precise durations of each and every interval of time to the exact shade of yellow in the windows dotting the crushed black nightscape behind the beautiful Vitalina’s exquisite three-quarter profile. Is Costa exploiting these people and places for their phantom beauty? You bet he is. Suppressing one’s own desires and attractions in the name of a hollow ideal of moral equivalency always has and always will make for lousy art. The point isn’t the attraction, but where you take it. Too much of the rhetoric around Costa is abstract, only beginning to approach the wondrous spells and haunted refrains of the new Horse Money. The artist himself reckons that he’s turned some kind of corner with this film, and so he has. Fleeter and more mobile than Colossal Youth, with a structure built on what Murnau eloquently described as “the most fleeting harmonies of atmosphere,” Horse Money finds its way into the centrifugal force that Charles Olson identified in Melville, the sense of the “inertial structure” of the revolving world itself.

The film begins with Jacob Riis’s images of the New York poor at the turn of the last century. And somehow, the very insistence of these photos tells us that this is not going to be a film about what people lack, but of what they have and who they are. “Remember Delgado?” asks one of the men standing at the edge of Ventura’s hospital bed, like the bomber crew saying goodbye to their captain in Hawks’s Air Force or the PT crew paying a last visit to their dying comrade in Ford’s They Were Expendable. “He tucked his sons into bed, waited for his wife to go to sleep, and set his house on fire.” And then there was Lento, who “had to sell drugs to make up his wage as a paver.” Sometimes you sell drugs, sometimes you go insane, and sometimes you walk the streets with a razor in your back pocket: no moralizing rhetoric, only the rule of solidarity between the filmmaker and the people he’s filming.

When Costa was interviewed for Cinema Scope, Mark Peranson asked him if he had shown any John Ford movies to Ventura. “Why would I show it to him when he’s the real thing?” he answered. “He lives in a Ford movie every day.” The image of friends at the bedside doesn’t feel like a “quote” in the musty sense of auteurist criticism, but a spark of continuity. A gesture transmitted by Ford and Hawks from the Forties gives the perfect form to comradeship in 21st-century Lisbon. These three men may or may not be ghosts conjured by Ventura during hours-stretching-to-eons in hospital beds and examination rooms and institutional elevators and brick corridors, where he finds himself walking and wandering, again and again, throughout this film. Far from searching for a Ford/Hawks effect, Costa is feeling his way through this ever-present and always urgent question of how to do justice to the lives of his friends, and finding kinship with these artists who also filmed only what and who they were drawn to film. But whereas Ford and Hawks, working in the studio system, sometimes systematized their own aesthetic choices, Costa seems to rethink his own movie with each new scene. Nothing is ever expected, visually or structurally, and everything is at the service of aligning himself with his tall, beautiful, quavering hero, endlessly circling around the time he got into a knife fight with a man in a red shirt named Joaquim, smack in the middle of the Carnation Revolution.

Horse Money, it has been said, happens mostly in Ventura’s head. The observation doesn’t get us very far, and could be said of one in 10 movies playing at any European film festival at any given time. What counts here is the institutionally induced entropic state that lays the groundwork for such mental wandering. To find yourself wedged between the facts of a failing body and a “healthcare system” whose lengthy intervals of nothingness allow you the privilege of experiencing the slow decay of time passing like water from a leaky faucet, where Davis’s “violence of economic exclusion” is most acutely and commonly felt—this is what Costa transposes into cinematic poetry. In Colossal Youth, it was a different shade of institutionalized horror: the destruction of Fontainhas and the displacement of its inhabitants to ridiculously, spotlessly white apartments. Here it’s the afflictions of tests and intakes and paperwork and endless waiting and walking up and down staircases and corridors, where the dead come and go… where your friend’s wife haunts you with her enchanted whisper… where an armed soldier appears as his own memorial in a time-stopping elevator… where you still need to hold on to your passport and your certificates of birth and death. And where you and the people around you become one. This is what the movie is about, because it is the movie. Costa reported to Peranson that after seeing Colossal Youth, one of Ventura’s neighbors told Ventura: “You’re a piece of shit every day in this neighborhood and we see you up there and you’re all of us.”

I could go on rhapsodizing about the wonders of Horse Money, which becomes more alluring and impressive with every viewing: the soundtrack, so lovingly layered, in which every voice is a character and nocturnal silence is the star; the sudden apparition of the boys in the trees, gazing down intently like warring gods; the great star-crossed Vitalina; and Ventura, alias José Tavares Borges, a broken man but, it seems, proudly so—proudly here. The moving force of this film originates with Ventura himself, and the spirit of fraternity from behind the camera.