Film Comment Recommends: The Practice of Disobedience

This article appeared in the August 5 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

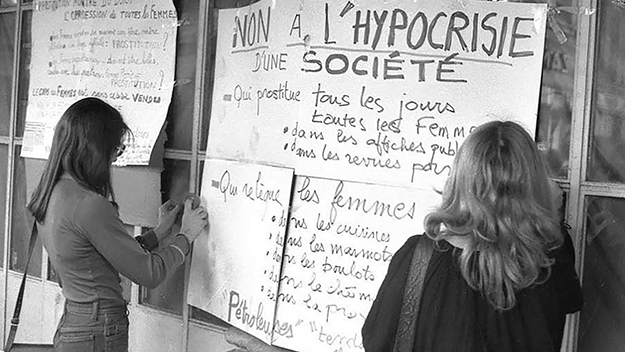

The Prostitutes of Lyon Speak Out (Les Insoumuses, 1975)

The Practice of Disobedience is available to stream on Another Screen.

“So, at the heart of it, your feminism consists of what, precisely?” a French television host asked actress, activist, and video-maker Delphine Seyrig during an interview in 1986. “In my communication with other women… listening to other women, talking with them,” Seyrig responded.

It’s a succinct summation of what the documentarian Carole Roussopoulos, Seyrig’s collaborator in the video collective Les Insoumuses, described as the collective’s éthique du tournage or ethics of filming: using the camera to amplify and empower the voices of women. Seyrig, Roussopoulos, and Seyrig’s close friend, the translator Ioana Wieder, founded Les Insoumuses—a play on the words “muse” and “insoumise,” or disobedience—soon after the explosion of public protest in France in 1968. The portable, tape-based Sony Portapak video camera was released in the same year, and Roussopoulos identified it as a powerful tool for distributing alternative media narratives, manifestos, and educational materials in service of Les Insoumuses’s political concerns: the legalization of sex work and abortion, and gay and lesbian liberation.

The videos of Les Insoumuses have been preserved and restored by the Paris-based Centre audiovisuel Simone de Beauvoir (co-founded by Roussopoulos, Seyrig, and Wieder in 1982), but occasions to see them in the U.S. have been sparse. This summer, by happenstance or providence, both MUBI and Another Screen, the free streaming platform run by the feminist journal Another Gaze, are screening a collection of Les Insoumuses’s works, while Anthology Film Archives is hosting a free online screening of the collective’s 1975 film, The Prostitutes of Lyon Speak Out. On Another Screen, these videos are accompanied by new contextual writing by Ros Murray, Antoine Idier, and Cassandra Troyan that focuses on the activists and protesters depicted in the films rather than their makers, reinforcing Les Insoumuses’s goal of decentering their own authorship.

Roussopoulos saw video as a more democratic medium than film—it was cheaper, she could film uninterrupted for longer, and the footage was easier to edit. In 1971’s Le FHAR, a chronicle of the 1971 May Day protest by the titular Front homosexuel d’action révolutionnaire (Homosexual Front for Revolutionary Action), the steady pans and focus pulls of Roussopoulos’s long takes emphasize both the speaker (for the most part, the scathingly witty FHAR activist Anne-Marie Grélois) and her crowd of comrades in the same shot. The Prostitutes of Lyon Speak Out capitalizes on one of the major advantages of video: the possibility of an immediate turnaround between shooting and editing. The film records the occupation of the Saint-Nizier church in Lyon by 150 sex workers for eight days in June 1975. Roussopoulos was invited to film inside the church, where the sex workers were protesting the targeted harassment and exorbitant fines they were routinely subjected to by the French police. Roussopoulos would tape their conversations in the morning, select preferred takes with the striking workers, and then play the videos on television monitors embedded on the outside of the church in the afternoon. The final video cuts between footage of the women making their demands, the crowds watching and reacting to the monitors outside the church, and voiceovers with black screens to protect the identities of certain speakers.

Just Don’t Fuck (1973) and Maso and Miso Go Boating (1976) use similarly revolutionary tactics, with videos of media broadcasts on television screens remixed and recontextualized with added commentary. In the case of Just Don’t Fuck, this culminates in an unflinching but sensitively depicted recording of an illegal abortion. This duality of militant sensitivity and empathetic deference to the subject is the backbone of Les Insoumuses’s work, which remains a spiriting archive of feminist dissent.

Mackenzie Lukenbill is an audiovisual archivist and editor and a Digital Archive Assistant at Film Comment.