Festivals: Projections 2017

Down Hear

For an experimental-film cinephile living on the East Coast, the trek to the city to spend a couple of days at Projections in the New York film Festival is an indispensable annual ritual. It is a feast for the eyes and spirit, an opportunity to exchange greetings and hugs with a community that extends across the country and world, and an incitement to think critically and appreciatively about the state of moving images. Now in its fourth year, Projections 2017 was an expanded four-day affair, consisting of six shorts programs, seven programs of longer or feature-length works, two retrospective events, and a 50-minute large-screen installation that screened continually on a loop. It was a diverse and eclectic mix, formally as well as geographically. Although not all the work was exceptional, some of it was. And the experience of such a broad swathe of recently made experimental films provided ample fodder for aesthetic pleasure, deliberation, and conversation.

It is a daunting task to bring together and showcase more than 25 hours of experimental work and over 50 films. Programmers Aily Nash and Dennis Lim expanded their curatorial ambitions for Projections this year, and the 2017 program offered exciting work for a variety of audience sensibilities. Commenting judiciously on even a small portion of this selection is difficult. I was not able to see every program, and some of what I saw left me indifferent, either because it felt derivative or dependent on previous knowledge of the artist’s conceptual preoccupations. Yet overall, a huge proportion of the works screened were interesting, provocative, and merit much more attention in a public arena.

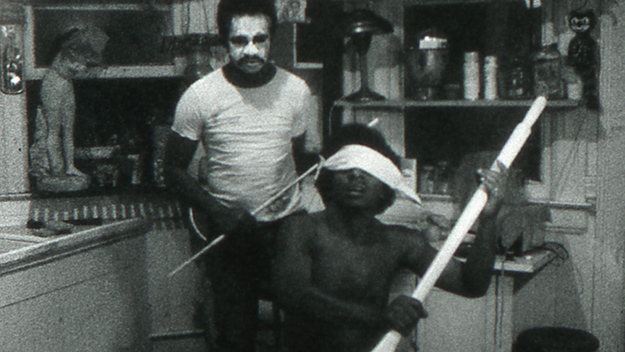

The two retrospective programs featured 16mm films recently preserved by the Academy Film Archive. Programs of work by Mike Henderson—one of the few African American artists making experimental films in the 1970s—and grande dame of American queer experimental cinema Barbara Hammer were a significant addition to the overall Projections line-up. It was a pity they (especially Hammer’s program which was placed on Monday) weren’t screened earlier as they formed an interesting counterpoint to some of the contemporary work following in their historical wake. The sheer exuberance of these films of the 1970s and ’80s, the unbridled sensuality and sexuality of Hammer’s films and the raucous absurdity of some of Henderson’s, is moving, as is their fierce commitment to play and provocation. There is an unrestrained aesthetic and political energy, as well as a willingness to risk all and put one’s body where one’s beliefs are, that seems rare in most works of today.

Good Luck

Among the films that stood out most to me were those that engaged with the social and political world in wildly different ways. These included new long-form works by prolific Projections regulars Kevin Jerome Everson and Ben Russell. Everson’s Tonsler Park patiently explores the unassuming and generous gestures of volunteer workers and voters in a polling station in a largely African-American neighborhood in Virginia. Given the cynicism and dismay that now surround our last presidential election, this portrait of a community interacting around that fundamental democratic act of casting ballots is particularly affecting. Ben Russell’s Good Luck juxtaposes industrial copper mines and miners deep under the ground in Serbia in Part 1 with a return (Russell shot part of his 2009 Let Each One Go Where He May there) to the informal, open-air gold mines in Suriname in Part 2. The film centers primarily on the onerous labor of excavation and extraction—digging, drilling, beating, sucking, scraping stuff from the earth—as male bodies navigate and manipulate constrained and arduous physical spaces for their living. Russell is a master cinematographer who moves with and around his subjects in long takes as they work. He offers us a sense of these worlds where vulnerable men with violently vibrating machines force the obstinate earth to yield its ore and in the process form community. Between scenes of work, Russell places almost tender moving black and white close-up portraits of the individual miners, seeming to look into the camera, at us, and into themselves in moments of respite.

Many of the shorts across a number of programs also played with representations of our strange, horrific, and wondrous world in inventive ways, some documentary, some moving toward fiction. Ephraim Asili’s 16mm Fluid Frontiers is a beautiful and complex portrait of Detroit (by way of Windsor, Ontario) and a reflection on African-American history and poetry. Asili intermingles powerful spontaneous readings of poems by Audre Lorde, Sonia Sanchez, and others by Detroit residents—all taken from publications by a now defunct independent Black press—with audio of Margaret Walker reading her poem about Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railway. Marta Mateus’ visually stunning Barbs, Wasteland also recapitulates and invigorates history through Brechtian testimonies and reenactments of agrarian reform, the Carnation Revolution, and folk beliefs in a rural village in southern Portugal. In Fantasy Sentences, Dane Komljen deploys striking Soviet Block or Ukrainian home movies of children sledding, happy family outings, and animated student gatherings that slowly transform, via the passage through a forest, into what looks like images of devastated and depopulated Pripyat, the city next to Chernobyl. Pia Borg’s Silica sets a narrative of a professional location scout against her visual exploration of an Australian opal mining town. One of the most delightful hybrids of documentary and fiction was Jorge Jácome’s short Flores, which explores the effects on Portugal’s Azores islands of the hydrangea invasion that forced all inhabitants (except a neo-colonial French hydrangea laboratory) into exile on the mainland. Seen through the eyes of the narrator and two young soldiers working on the island whom he befriends, Flores creates a surreal and tender romance that comments on real issues of economic migration, national and regional identity and cultural loss. Each of these shorts used its images and narrative strategies to activate our imagination, to explore and revitalize history, and to stimulate curiosity and empathy.

Several other poetic or philosophical films also left vivid imprints on mind and body. Some still linger a months later, seeming to demand some kind of response. Three of these were screened as part of the aesthetically and philosophically nourishing program titled “The Shapes of Things.” The program began with Jonathan Schwartz’s The Crack-Up, an excursion through fear, near collapse, and transformation that takes its name from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1936 autobiographical essay. Reflecting on life’s “process of breaking down,” it is both extremely personal and also relevant to the difficult times we live in. With sublime 16mm footage of glaciers, monumental snow-covered landscapes, and an icy, roiling sea, The Crack-Up alternates strident sounds and brash rhythms and gestures of the camera with moments of arresting fragility and grace. Danger, death, the unexpected chaos and destruction of life are all evoked with almost no human presence in the image. The sound of wind, rain, the cracking of frozen earth occasionally gives way to two voices—a female voice reciting from Fitzgerald’s text and a male voice struggling to use language at all. Schwartz’s film seems to take as its challenge Fitzgerald’s admonition to simultaneously “see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise.”

The Crack-Up

The Crack-Up begins with a ferocious rumble of wind and microphone noise over short, staccato shots moving up over a snow and ice-filled topography. A hint of blood-red liquid seeps through, forming ink-like stains on this vision of a crystalline, cold world. Notes of piano practice, then an out-of-key chord accompany more arctic landscape but with occasional traces of flowers appearing, as if gesturing towards a tentative but uncertain possibility of transformation. A voice struggles with speech, haltingly, trying to form sentences. It is the unrelenting confrontation of language/ naming with all that resolutely remains beyond its grasp in our lives. This inability to craft coherent phrases to tame or frame the inhuman world we see on the screen embodies our very human condition.

Stunning Icelandic land- and seascapes dominate The Crack-Up’s imagery, but shot in short rhythmic bursts, with forceful camera movements and different exposures so that the same image can shift from gloriously luminescent to darkly foreboding. Varying times of day and weather result in a vivid depiction of the symbiosis of earth’s topography with the sun and atmosphere. Gentle snow-covered curves alternate with large- and small-scale jagged icy surfaces, and there is a magnificent sequence of blocks of ice being rocked and eroded by powerful ocean waves. Aside from tenuous flowers that appear and disappear beneath this blue-grey-white and glassy world, the film also briefly introduces other landscapes, including a cemetery with the gravestone of the filmmaker’s mother. Towards the end of the film there are moments with no light, the appearance of no-thing, perhaps only grief.

Fitzgerald’s text distinguishes between blows that come to one from the outside and those from within, the latter that “you don’t feel until it’s too late to do anything about it.” Indeed, one can “crack in many ways” Fitzgerald writes. Schwartz’s film suggests that such cracking besets (or will beset) us all. It is this that makes us human, and also makes our watery blue planet hurtling through space so vulnerable. His use of film to depict the ineffable battle between despair and hope, between anguish and buoyancy in response to a cracking from inside and out—is profoundly moving. At the conclusion of the film, the male voice again struggles to recite some lines from Donovan’s “Catch the Wind”: “Uncertainty. … Uncertainty. May as well try to catch the wind.” What remains with us as the film goes to black is the penetrating acknowledgment of that uncertainty, the uncertainty about the fate of each and every one of us and of the planet as a whole. Asserting this shared vulnerability, The Crack-Up engenders the intermingled hopelessness and radical determination that is our sole option.

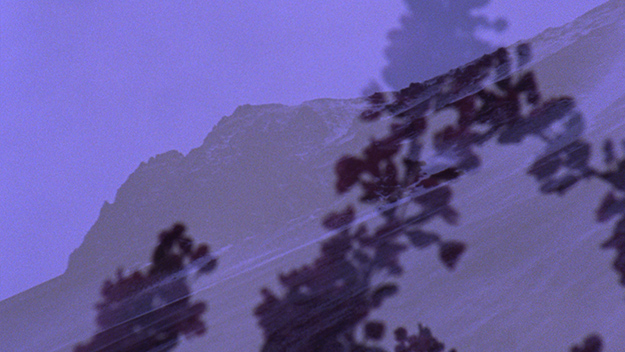

St Bathans Repetitions 16.2.1-16.3.17

Schwartz’s film was followed by a new work by Canadian Alexandre Larose. I am familiar with Larose’s astonishing in-camera superimpositions, yet the delicate, ghostly visual incarnations of St Bathans Repetitions 16.2.1-16.3.17 was profoundly beautiful and moving. Set in a small mining town in New Zealand where Larose did a multi-month residency, this piece deploys his multiple exposures to new ends. An old mining cottage becomes the stage for a meditation not only on movement and gesture, as in the earlier works, but also on the passage between inside and outside, window and world, youth and age, separation and return. Three hand-developed film studies of this interior/exterior space are separated by one interlude that is a shimmering sepia-silver ode to the surrounding topography of dry earth, rock, and mineral of the once-mined terrain. Like Larose’s other work, St. Bathans Repetitions is a rumination on movement, a vision—somewhat similar to the chronophotography of Etienne-Jules Marey—that both distends and concentrates the flow of motion-in-time into a single space. Made by meticulously shooting dozens of super-imposed sequences on the same role of film, the work suggests, on the one hand, the impermanence and the transience of all things. On the other, it underscores the felt traces—inexorable if evanescent celluloid impressions—that a transient body’s passage always leaves behind.

A four-paned window, a wooden screen door, a small settee with a footstool, a patterned curtain. These are some of the elements of the space which Larose explores and in which he places a silver-haired man, entering, settling in, rising again. His movement, however, seems to fragment, proliferate, flutter. Dozens of superimpositions release the cinematic appearance of time over time. Gestures: entering through the screen door, walking in front of a window, opening a curtain, turning to close the door, placing a hand on the surface of the couch, crossing a leg. In their ephemeral multitude, these motions contrast with the more permanent materials—the glass, wood, wire mesh, and brick of the room and its fixtures that also heave and darken with the multiple passes of their reflected light onto the surface of film. The window becomes an epicenter of the work, with its simultaneous partition and conjoining of inside and outside, alongside the wooden screen door with its promise of passage, and the chair next to the window, a site for observation and reflection. Repeatedly the man comes in to sit, or opens a closed curtain to reveal the outside world. We see him exit and enter into the sunlight as well, and watch him through the window from inside out, always in motion as if he is a continuum that cannot be fixed but only intimated. Similar but never the same—neither the movements, nor the light, nor the man.

With St Bathans Repetitions, Larose has made a hymn to the liminal, to the experiential thresholds of time and space and cinema’s distillation of light and dark (both black and white and color). But it is also a meditation on bodily incarnation and our intangible, precarious hold on life as we move through it. Knowing that the figure in the film is Larose’s father suggests the shifting symbioses of parent and child and the respective arrivals and departures of varying stages of adulthood. The father, Jacques Larose, materializes and dematerializes as he enters and leaves the filmmaker’s chosen interior space. He is model and guide, a tender embodiment of becoming that crisscrosses windows and thresholds, both present and not for his acutely observing son.

On Generation and Corruption

The final film in the “The Shapes of Things” program was On Generation and Corruption by Takashi Makino, also a frequent artist at Projections. Opening with a flash of red and then going to almost-black for several minutes before revealing dense, mysterious landscapes of blues and greens, Makino’s film draws one through its permeated visual surfaces into a world tantalizingly on the verge of being discernable. At once abstract and immersive, the images provoke shifting attention to two-dimensional space and three-dimensional place. Consisting of multiple layers of imagery shot in and around Tokyo and its water sites, the work invites us to continually seek to see. Yet its moving shapes, gorgeous shifting color palettes, and transforming textures never provide us with anything definite, anything concrete. Because it engages both our eyes and our inquisitive and creative imagination with its indecipherable imagery, no two people will have the same experience. With Jim O’Rourke’s striking minimalist soundtrack, we are taken on a journey where incomprehensible forces, landscapes, and objects seem about to emerge only to then recede again into the swirling mass.

Each viewer brings their own associations and imagination to the experience of On Generation and Corruption. At times I am eerily lost in the beautiful sea fog of a J.M.W. Turner painting, at other times thrown between Monet’s poppy fields and his waterlillies, experiencing them as if from above but also from below. Water becomes waves or flowers, becomes trees in a dense forest, becomes cityscape. At another moment I am reminded of Walter Benjamin’s “Angel of History.” While we humans fantasize that our time embodies progress and exists as rational chains of events, the Angel, according to Benjamin, “sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet.” Makino’s film embodies the very tissue of this rubble that is our history. Still at other moments Balzac’s Frenhofer comes to mind—an artist who filled his canvas with so much detail and passion that nothing is left discernable to anyone else.

One visual recurs: flecks of white light leaping around the space of the screen. It is as if so much (or nothing at all) has been exposed in these small points that they have burned through the celluloid and digital surface. Even a bleak semi-tangible world must leave its obstinate sparks of white light. They sometimes appear (to this viewer) as a vast field of fireflies at night, dancing for us; at other moments, a star-filled cosmos we are hurtling through; then luminous underwater plankton deep in the ocean. Sometimes they grow and recede. Although any perception of objects remains unresolved in Makino’s work, the experience of motion itself does not. At times the image pulls us into or across itself through its motion, at other times it is as if we can trace and follow movements of … something—whether a surge or flow of earthly elements, or simply the life force itself. On Generation and Corruption’s images are always dynamic, as if the film might, upon another viewing, divulge the secrets of this incomprehensible and abstract drama. O’Rourke’s musical score brings its own moods, from contemplative to anguished, occasionally suggesting breath, not so much a calm meditative breath but a fraught, determined sucking in and out of life.

Caniba

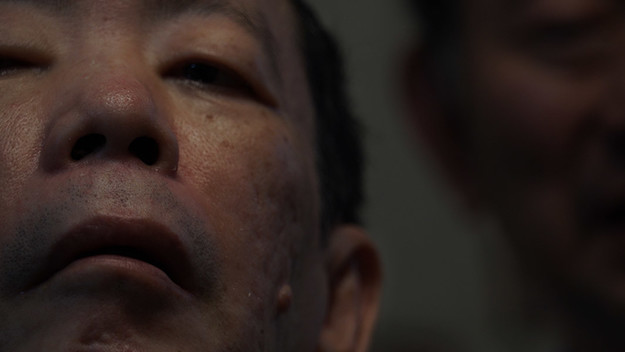

Finally, one of the most anticipated but (to this viewer) disappointing programs was Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s feature-length Caniba, an idiosyncratic portrait of the “cannibal” Issei Sagawa and his brother and caretaker Jun Sagawa. Cannibalism, whether figurative, literal, or simply a paradigmatic object of moral taboo, is clearly a topic of fascination in our culture. Castaing-Taylor and Paravel’s film makes an explicit point of neither condemning nor endorsing the actions of its subject. We are left to face the hour-and-a-half portrait of Sagawa with no palpable ethical framework but our own.

And “face” it we must, for the vast majority of the work consists of shots in extreme close-up of Sagawa’s face alongside or in front of his brother’s. With minimal depth of field, often one of their faces is in focus while the other is not, and this seems unconnected to which of the two is speaking. Claustrophobic is one way of expressing the experience provoked by this closeness to the fleshy materiality of an aging, unhealthy face of a man who, post-stroke, offers occasional pithy lines but more often seems consumed by his own narcissism, his past, and others’ fascination with him. The camera’s telephoto proximity to this flesh—or at least its unwillingness to look anywhere else—presses up against it as if to partake in Sagawa’s abject, fleshy and flesh-eating desires. Repeatedly I had the sense that I was being forcibly pushed so close to this skin as if about to consume it. It is no longer the face of a human being, but just skin, the old, pimply facial skin of an unhappy, ailing creature. A creature who happens to be a man and a murderer.

Sagawa, while not a household name in the U.S., is not unknown either. In fact, he was even the focus of a half-hour Vice Meets video still available on the Internet. In 1983 while studying in Paris he murdered a 25 year-old Dutch woman who came to his apartment to study with him. After killing her, he dismembered her body and ate parts of it before attempting to throw out the rest. Returning to Japan after being declared legally insane, he survived economically by reenacting his crime, acting in porn, and producing manga with a graphic first-person account of his murder, dissection, and consumption of pieces of the young woman’s flesh.

Caniba

There is something paradoxical in the film festival world’s attraction to this film and this character given recent media “sensitivity” to the plight of young women at the hands of sexually predatory men. The attention to—or fetishism of—cannibalism and the desire to consume or merge with another human that Sagawa repeatedly expresses in his tale of desire for the young Renée Hartevelt diminishes the fact that he first murdered her, shooting her from behind, after luring her to his apartment. Castaing-Taylor and Paravel’s film is less interested in him as a murderer-rapist. Yet it is not particularly revealing about his cannibalistic impulses either. Where it does provide some insight is in the ambiguous, close relationship between the two brothers which shifts during the process of filmmaking as Jun Sagawa is confronted with the graphic details of Issei’s manga-drawn murder-cum-meal. Jun then reveals (and demonstrates for the filmmakers) his own fetish of cutting himself with barbed-wire and knives. The scene plays out as if Jun is desperately trying to impress his notorious brother Issei, to get attention from him and others for his own suffering and hidden debauchery. We see impassivity and then tears on Issei’s face when Jun asks him if he is shocked. Whether they are tears of empathy, pity, or just more narcissism, we cannot know.

Ultimately, Caniba is a portrait, but it is not an especially illuminating one, once we get past (and over) the sensationalism implied by the title. While the shallow depth-of-field close-ups will intellectually or somatically excite some viewers and repulse others, the rest of the filmmaking is comparatively conventional. The film may appeal to those interested in Sagawa, but Sagawa has already had much more than his 15-minutes of fame. Caniba does little to critique or contextualize that and ultimately feels self-serving in its contribution to the obsessive retelling of a lurid murder.

Projections provides an amazing opportunity to experience what non-mainstream film and video can do with and for the world. In my experience, this section of the New York Film Festival is getting more exciting every year. Aside from the ever broader selection of work, both new and newly restored, Projections also provides one of the best physical spaces in which to see and hear projected film and video. Kudos to the projectionists, all the staff in the booth and elsewhere, as well as to the programmers for gathering together and sharing this year’s expansive range of moving image work.

Irina Leimbacher is Associate Professor of Film Studies at Keene State College in New Hampshire and a former curator of experimental and nonfiction film.