Interview: Ben Russell

In both shape and sensibility, the work of Los Angeles-based filmmaker Ben Russell embodies a fluid yet holistic creative practice. Combining elements of ethnography, surrealism, observational nonfiction, and trance cinema, Russell’s multivalent output finds unique expression in both the art and film worlds. For almost two decades, Russell, one of the most celebrated experimental filmmakers of his generation, has moved effortlessly between cinema and the gallery with a prolific run of short, medium, and feature-length works. A spiritual descendant of cinematic anthropologists Jean Rouch and Robert Gardner, Russell has consistently worked to disrupt traditional bounds of ethnographic filmmaking through a singular stylistic admixture that boldly merges the musical and the mystical, an approach that sets him apart from such like-minded contemporaries as Britain’s Ben Rivers and the past and present affiliates of Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab (Lucien-Castaing Taylor, Véréna Paravel, J.P. Sniadecki, et al).

Following a number of shorts, Russell’s first feature, Let Each One Go Where He May (2009), a film consisting of 13 unbroken shots, each running roughly ten minutes in length, made for a striking and impressively cohesive statement upon its premiere in the Wavelengths section at the Toronto Film Festival. Four years later, A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness (2013), a transfixing three-part travelogue co-directed by Rivers that bowed in Locarno’s Signs of Life program, confirmed the filmmaker’s growing stature and increased ambition. Russell’s latest feature, the two-part, 143-minute Good Luck, continues this upward trajectory; premiering in competition at Locarno, the film is a bifurcated study of two mining communities on either end of the earth.

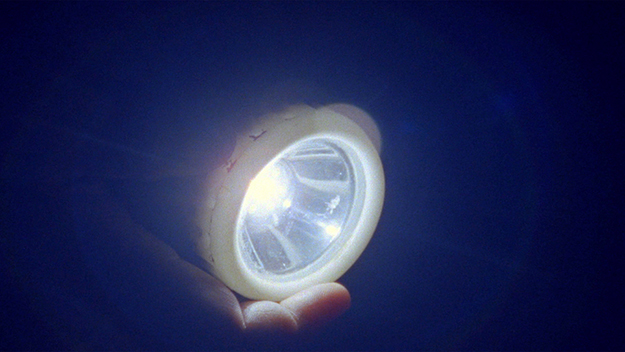

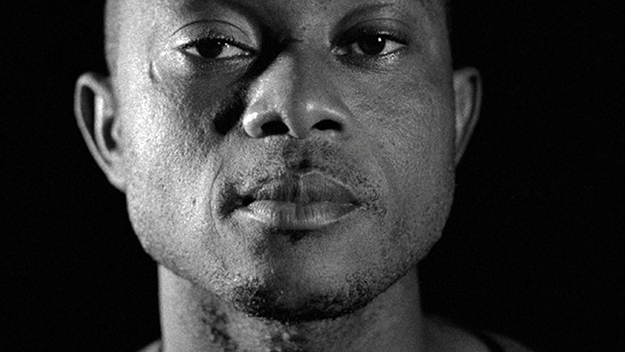

Set successively in an underground copper mine in Bor, Serbia and an open-air gold mine in the Brokopondo district of Suriname, the film’s two sections are punctuated by a pair of musical sequences and a series of Warholian portraits of the workers seated in stoic solitude. Focusing on the bodies of the miners as they navigate extreme environments with matter-of-fact vigor, Russell frames the differences and the common points between two communities linked by manual labor, capitalism, and the demands of globalized trade. In patient, dream-like strides, Russell’s Super 16mm camera intrepidly follows the miners into the cold depths of the Serbian copper reserves and through the mud-choked expanses of the Suriname jungle, presenting a mirrored, intimate account of two environments whose contrasts only reinforce the reciprocal nature of an increasingly global enterprise.

In the interval between the film’s premiere in Locarno and its North American presentations at the Toronto and New York film festivals, Russell spent an afternoon watching Good Luck with Film Comment. This conversation took place as the film, projected on a wall in his Los Angeles home, played quietly in the background. Good Luck will have its U.S. premiere on October 7 and 8 in Projections at the New York Film Festival.

For a long time prior to seeing the film my conception of the project was that it was a film solely about miners set in Serbia. Come to find out it’s much larger and more ambitious than that. Was the film always conceived as a two-part work set in different locations?

Yeah, it was always meant to be in two parts, and two different spaces. I had first been to the mine in Suriname in 2007 and have been back a bunch in the interim, and I always wanted to make a film there. There are a lot of films that depict labor—and labor performed by black bodies in particular—that think about labor as a whole practice, and those representations don’t tend to be totally human. They’re not thinking about the subjects as subjects. They’re thinking about them as actors or performers within a larger system. I didn’t really feel like I needed to add to that. And because I’ve spent a lot of time in Suriname, and I speak Saramaccan, and I know these guys pretty well, I feel like my interest is much more in the humans, in the men working there, and how they’re working and who they are as a kind of collective—but definitely not as representatives of a third world or an exploited labor force. I felt like I needed a way for the audience to address them as humans and not as bodies. Because I assume most of the audience is not going to be Saramaccan, or West African—it’s mostly going to be Western Europeans or Americans. So I was looking for an opposite set of circumstances that were happening within the same loose framework. Beginning the film with the Serbian community will hopefully allow a different kind of humanity to manifest by the time you get to the Saramaccan workers. By then you’ve already been thinking about labor for an hour—hopefully by then the question of what the thing is is no longer spectacular. Your attention is now drawn to the people performing the work.

Tell me about this quote by Belgian poet and painter Henri Michaux that opens the film. (“Now I am in front of a rock. It splits. No, it is no longer split. It is as before. Again it is split in two. No, it is not split at all. It splits once more…”)

I was in a show in Paris a few years ago and there was another artist showing drawings he had made while on mescaline, and this led me to this Henri Michaux book, Miserable Miracle, which is a document of his experiences using mescaline. So he’s dosing himself and writing about the experience, and this text is essentially a description of a hallucination of looking at a rock that’s opening and closing, and forming and unforming. I think with the work I’m trying to do it’s never really about representation or documentation but the production of some other kind of thing, and there’s a real hallucinatory quality to manual labor that happens over extended periods of time. So I think the text helped me think about the film as both a kind of physical and visceral hallucination, but also as a description of a process that never ends. I mean, this is what mining is: you’re just digging into the rocks, and digging into the rocks, and breaking them apart, which reveals more rock. It doesn’t have an end point. But I also really like that the book is called Miserable Miracle. It’s not an ecstatic, joyful description of psychedelic experience. It’s kind of terrible—ecstatic at times, maybe, but also really overwhelming.

Now we’re watching the opening sequence, a single extended shot of a brass band emerging from a dilapidated house and marching down a dirt road. How does this shot play into that psychedelic dimension? Were you looking to visually extend the quote’s visceral qualities?

It’s always easier to talk about the film as a thing that comes into formation in its entirety, where everything happens in the order you see the thing. But the truth is, or at least in the way that I’ve made this film, by looking for a place and then finding another place and then moving between places, there is always an aspect—especially when you’re dealing with a nonfiction subject—of finding things that aren’t the things that should be, or the things that you want them to be, and those things always kind of mutate and shift. So the opening of the film was always the opening, but the text wasn’t always at the beginning. And this circle graphic that I arrived at, which bookends the film, is something that happened in the editing. So it wasn’t fully formed until it was finished.

But the opening shot, which is an image of a landscape in Suriname that crossfades into this open pit mine, which is the largest open pit mine in Western Europe—it felt like that jungle was potentially this mine, which was potentially that jungle, like these things are locked in a kind of interchange. And the sound that starts this off is a group of musicians who used to work as the official band of the mine, which is state-run and which was unsuccessfully privatized twice. There’s a Dušan Makavejev film called Man Is Not a Bird that was shot in this same mine and which features a much larger mining band. I think the guy marching on the right, either him or his uncle, was in the film. So the band used to work for the mine, and thus they already had a sense of themselves as cinema subjects to some extent. The drone you’re hearing at the beginning is them harmonizing with the drone of the pit.

For me it came down to how do you show a space that’s too big to film? And how do you speak towards a history that’s defined by destruction, appropriation, and capitalism? All these things are happening in this first shot of the mine, which seems like just a shot of the mine, but which is revealed to be an abandoned house, which is then revealed to be on a street with houses that are still existent. So now you kind of understand that this thing you’re standing on, this pit that you’re looking into, used to be part of a town. And this is articulated at the end of the shot when the drummer says, “I remember where my house was. I remember the kids were there.” He hadn’t actually been to this spot for 12 years, and he was very shocked by what he saw.

The circle graphic you mentioned immediately establishes a kind of duality, or mirrored logic that the film continually engages. How did you come to this symbol?

Editing this thing was tough. At points it felt like two separate films, and I wondered whether the mirrored aspects and the repetitions, the things I was trying to establish, were really happening. Especially with longer work, once you’ve been in it for a while it’s tough to get a sense of what it’s actually doing, or how it’s really functioning. So the Henri Michaux quote, and the crossfades, these are stranger moves that helped point towards an intention in terms of the construction of the whole thing. And coming off the triangle symbol that Ben Rivers and I used in A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness, where we were thinking about the shape of the film as a thing that requires all three sides to be present, it felt important to think of this two-part film as an entirety that was also divided in some way.

Did the mirroring aspects develop along the way? And were you finding more similarities between the two sections as you went along?

I spent a month shooting in Bor, and since I only went there once and wasn’t familiar with it I didn’t really know what the setup would be like. I had an idea, but as opposed to Suriname, which is where I shot part of Let Each One Go Where He May, I didn’t know what it would be. I actually had all the footage I shot in Bor processed and transferred so when we got to the mine in Suriname we could watch it on their TVs. So I was thinking about what kind of images were present, what kind of movements where present, what kinds of bodies and faces and those kinds of things, so there could be a direct and intentional line between the two spaces. So it had a pretty clear structural device which I imagined as a mirror where the middle folds out and where one thing goes in towards the center and another thing goes out from the center. But there were things in terms of time and access and people—there were all these practical and human concerns that maybe kept that from happening in such a formal way, which I think is perhaps more interesting but which was tougher to arrive at.

For example, it was really easy to use the Steadicam in Serbia, because the men are working with machines that travel down paths. So while the roads are a little fucked up and muddy and stony it’s still totally possible to move through those spaces. But in Suriname you could walk on a path and the surface one step over might look exactly the same, but if you step into it you could fall up to your thigh in mud and lose your boot. On the flip side it was much easier to shoot handheld in Suriname than in Serbia because of all these gigantic machines in the Serbian mine that give off all this exhaust, which kept us from getting too close to the workers, both physically and personally. My relationship with the Saramaccans was totally different than it was with the men in Serbia. I don’t speak Serbian, so my affinity with them was much more superficial, whereas I think something much warmer and more personal happens in the Suriname section. But then we could also talk about stereotypes of the Eastern European temperament as being much colder anyway. [Laughs]

How did you find the Serbian mine?

It turns out it’s kind of difficult for artists to make films in corporate mining sites. [Laughs] So we spent a lot of time contacting sites and trying to get access. Really early on we went to a gold mine in Northern Finland that’s run by a Canadian company, but it felt too clean and didn’t have the qualities I was looking for. It took another two or three years to get access to this particular Serbian mine. In an ideal world I wanted something cold and dark and bit more institutional than what was happening in Suriname, just as a counterpoint. We were able to use the connections of one of the film’s co-producers, who’s Croatian and lives in France, to get access to the mine in Serbia, which hit all the points I was looking for in various ways.

What was it like filming and interacting with the Serbian workers? There are a couple brief scenes where you’re filming their break time conversations, but for the most part you’re following or shooting them with little interaction.

It’s complicated because all these guys work for a company, and that company is the state. I had a Serbian guy from the town nearby on hand to translate, and two other people on the crew spoke Serbian, and none of them were really able to crack these guys. The conversations that do appear in the film were all shot towards the end, after about a month of trying to get them to talk about anything, really, in any meaningful way.

Is that because you’re there as a filmmaker, as an outsider?

I don’t know, really. And I have no way of knowing. The things that I saw, the dynamic of men amongst men, is that you’re not going to disclose all your secrets or fears or desires in front your co-workers—whether you’re male or female, that’s not something that really happens, even if you spend all day every day with them. And being filmed is a pretty uncommon act. There’s nothing natural about it. There’s nothing natural about having a guy point a recorder at you while somebody else holds a camera and lights shine in your general direction—there’s nothing objective about it. So all of those things produce an artificial situation. Part of my approach is to spend a lot of time in these situations, especially when I don’t know the people well. I don’t like to film for the first week or two as I’m talking to people and figuring out who is going to collaborate or participate and who wants to be a part of this thing, while seeing what I can get away with and where I can shoot, so I can get past the point of feeling excited about everything I see, which is what I feel happens to everybody when they go to a new place.

We tried a bunch of different strategies to talk to these guys: we tried talking to them outside the mine, we went to dinner with them, we met them in bars—and except for the strategies we arrived at none of them really produced much material. It’s tough to film people and have them say really exciting, meaningful things off the bat. But often times this results in a didacticism or directness that I’m not really interested in in my cinema anyway—I don’t like having people explain what they’re doing or how long they’ve been there or why they’re there or whether they like it or if they have kids. I think there were other, more interesting ways to arrive at the structure we arrived at. And I think the system is evident in these conversations where you hear the sound recordist asking the same question over and over—that was my directive to him. We had a list of questions, and I told him to just ask them. If they’re not going to say anything—it’s frustrating but it’s fine. And there are also these engineers from the surface who are monitoring us but also watching them—power is always present in the construction of these scenes.

You’ve filmed in extreme settings before, but these underground scenes must have been particularly intense and difficult to shoot. In this shot we’re looking at, you’re right up close to a huge machine drilling into the earth.

Yeah, that was crazy. That was all Chris Fawcett, my Steadicam guy. He’s got great instincts. I mean, that was fucking nuts, but you’re not going to be like, “Chris!” One because he probably can’t hear you but also because I trust him and I trust his instincts. That shot is incredible. We only shot it once.

Tell me about the portrait sequences that punctuate the beginning, middle, and end of the film.

They were also there from the beginning. In a really broad sense my practice is mostly involved in a kind of portraiture, so a lot of these formal and structural conceits were things I was trying to work out visually. Stylistically I was of course thinking of Warhol. The portraits were all shot on black-and-white Super 16 and I hand-processed all the footage in buckets. But I think these sequences came out of a desire to let subjects speak for themselves and to place the audience into a direct regard with these men. I was aware of the fact that just filming men working would probably reduce them to the character of bodies involved in labor. So pulling them out and asking the audience to sort of be present with them will hopefully allow those faces to come the fore but also ask for a deeper psychological understanding or empathy. Because the film is intentionally a bit overwhelming in terms of duration and sonic character, and it’s easy within those moments to slip into being a spectator and forget that you’re in the presence of bodies who are working and breathing and doing the work on a regular basis. So it felt important to bring these faces to the fore, in order to feel what it is to be in a space or a time like this.

There was also an installation version of the film, which premiered this summer at documenta 14, that features sequences from the film running simultaneously in different rooms, plus additional channels that create a unique sonic and spatial experience for the viewer. As far as the theatrical film, the structure takes the audience from darkness to light, coldness to warmth, underground to aboveground, white bodies to black bodies, etc. How important was the ordering of the two parts in establishing this contrast?

For the viewer, the experience of the film as a film is one of being forced to think about Serbia while Suriname is on screen, while not having the opportunity to think about Suriname while Serbia is happening. That doesn’t necessarily happen in the installation, because your individual experience depends on many things: when you arrive, how long you choose to stay, what room you choose to stand in, and where you are at any give time within the four loops. I have a thesis about the film, which is that men are the same—which is obviously not the case. But conditions of manual labor, of mining, of mineral extraction produce a certain kind of relationship between groups of men. and that relationship exists across multiple spaces. The fact of labor produces proximity which brings out this other fact of being human, which everybody has in common. So my hope isn’t that we go from white bodies to black bodies, but that we go from bodies to bodies. Because we’ve been trained during the first part to think of the Serbian miners as individuals working within a collective or a community, my hope is that we’re ready to do that when we arrive in Suriname.

This sequence that begins the Suriname section—a lengthy unbroken shot following a young man from behind as he walks down a muddy path—is something of a prototypical Ben Russell image. What is it about these kinds of shots that interests you?

Well, for one, it’s really fucking hard to shoot someone from the front! [Laughs] It’s just tough to walk backwards. And particularly when you’re walking in front of a subject they’re fully aware of your presence and it’s their job to pretend they’re not looking at you, that they don’t see you. The guy in this shot is really carrying an oil can, he’s actually going to fill up the machine, and if there were four white people walking in front of him—or anyone, just people with cameras—his countenance and movements would be very different, because his experience would be really different. And those kinds of shots just feel to me like faux naturalism.

I like the kind of God’s-eye-view, third person, floating perspective that the following shot suggests. But there are other reasons: you also get to see a space coming into being. When we get to the end of this shot, you know where the guy’s been coming from the whole time, but you haven’t seen it, it hasn’t been revealed. When we finally get to the other side of the lake and the camera turns, you understand the scope of the space and the process. There’s a lot less movement available when you’re in front of a subject. Your attention is on the face and the body and not so much on the landscape, or the shifts in topography.

I’m always a little suspicious of too much subject affinity, which I think a camera in front of a subject proposes. Like, I speak Saramaccan and I’ve been going to this place for twenty years and I have good friends there, but I’m not Saramaccan and I can’t make any claims for who these people are. I can’t and don’t want to speak for them. And it feels important in a nonfiction practice that there’s an occasional return in awareness to the constructedness of cinema.

The Suriname section has a somewhat looser, more casual feel to it the Serbian half. What was it like shooting this section? It seems to be less regimented than the Serbian shoot and as a result more intimate.

We lived on site at the mine for a month. In Serbia the mine is a factory, so the guys go to work and then they go home. In Suriname everyone lives on site and only goes into town every few weeks. At one point there was a five of us, but for the most part there was only three of us. Like I said, I speak the language so it makes it easier to hang out. In my experience Saramaccan’s talk a lot. It’s a very strong oral culture. Most of them are illiterate and so most historical and cultural information is passed down orally. One of the amazing things about Let Each One Go Where He May is that the subjects don’t talk at all. But I had to work really hard to get them to not talk, because that’s not at all their impulse. It seemed pointless to try and translate and relay text in a film that’s always moving. Here it seemed necessary to have a bit more speech.

Your ethnographic instincts and surrealist interests usually prompt a certain set of reference points. You mentioned Warhol earlier—are there other films or filmmakers that you looked toward for this film?

As far as films that represent labor, I was thinking of Barbara Kopple’s Harlan County, USA and Phil Niblock’s The Movement of People Working. And also Tropical Malady, particularly in how it’s split in two parts and proposes similar movements between contrasting things. I realize now that as I’ve been talking about it the film might sound macho or extreme, which I hope it’s not. I’m not cut from that cloth. I’m no Michael Glawogger. But his work does have a lot of similarities with this film, particularly Workingman’s Death. I was really thinking about how to avoid making that film. Because I’m using a Steadicam. I’m filming a certain kind of labor. I’m in a place that’s pretty rough and tumble: how do I not make a film that’s already been made, and how do I find a different set of relations?

The relations you do find seem to draw out a subtle political dimension that feels unique in contemporary ethnographic cinema, and totally foreign to most documentary filmmaking.

I’m really resistant to the idea of documentary. I’m not super comfortable with it. And that’s an old idea—it seems fair that not everyone would be comfortable with it. There’s a lot more play that can happen within the construction of a space while still being reliant on subjects and presences—something more about cinema itself. I should say that for me it wasn’t really about white bodies and black bodies, or third world. When we see images of the mining conditions in, say, the Congo, or West Africa or Mexico, where things seem really terrible, and you’re just disgusted by the degree of exploitation and destruction—that shit is exponentially worse in commercial mines, but no one is getting access to commercial mines to see it. So it felt important not just to indict the developing world—to not point one’s finger at these guys and say they’re the ones responsible. Because we’re responsible as well. For the film it was important to have copper and gold in this relationship, because the gold miners use copper to do what they’re doing—their machines are made of copper. And gold purchases the equipment used in the copper mines. It’s all there and it’s something we’re all implicated in.

My interest in this wasn’t at all to say that mining is bad. Because I don’t think I have to say it—obviously it’s bad. It’s a fucked-up process and it’s terribly destructive. But it’s also been going on forever. That’s one of the rationalizations I had for shooting on film, because film has silver halide crystals, and silver is a byproduct of the earth. Surely there’s a lot in digital cameras that make use of minerals or whatever. But it just seemed like there was a pretty direct and important correlation to be made between film and the earth.

The musical sequence that ends the film underlines its circular or reciprocal nature. Did the workers often perform like this?

Yeah, everyone there seems to play in a Katawina band. Since I had gotten the accordion player to perform in Serbia, I wanted to find some musical relation on the other side, so the film would open and close with a song—very different kinds of songs. It’s easy for me to image this performance as somehow the beginning of the mine in Serbia, like there’s a different kind of circularity happening. I thought a lot about the two parts while putting it all together—like, if it is two films, then what do they accomplish on their own? An argument for one part over the other felt really thin to me. If it’s just a mine in Serbia, or just a mine in Suriname—that’s cool I guess, but the dialectic is what really pushes it forward and creates the conflict. That’s where the energy comes into being, in having to think about these two things in relation to each another and how to negotiate those extremes.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs the experimental screening series Acropolis Cinema and is co-artistic director of the Locarno in Los Angeles Film Festival.