Dispatch: Qumra 2019

Alice Rohrwacher at Qumra in Doha, Qatar. (Photo by Eamonn M. McCormack/Getty Images for Doha Film Institute)

If you’ve been to an international film festival at any point in the last decade, you’re likely familiar with the Doha Film Institute. Since 2010, the DFI has provided funding for film projects through multiple grants and co-financing programs, supporting work by first- and second-time filmmakers. So extensive are their efforts that the organization’s name pops up in the credits of what seems like every fifth film, across titles of various lengths and persuasions. Among their projects, female filmmakers and directors of Qatari descent take pride of place, as does topical subject matter and films of a certain sociopolitical perspective. In 2019, with Qatar under heavy scrutiny for its ties to Iran and alleged support of several Islamist movements—a situation that led to an ongoing land and sea blockade imposed by Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates—the DFI’s continued support of politically conscious and engaged cinema feels more urgent than ever.

These events were never far from the minds of those at this year’s Qumra, the DFI’s annual industry summit held in Qatar’s coastal capitol of Doha. Now in its fifth edition, Qumra brings together filmmakers, producers, programmers, festival directors, and journalists for a six day convention of panels, screenings, workshops, meet and greets, masterclasses, and a variety of ancillary activities. This year, 36 DFI funded projects from 19 different countries were invited to participate in the event, providing one-on-one opportunities for the talent to meet and discuss their projects with both industry professionals and established filmmakers. Each day, guests gathered over breakfast and lunch to provide feedback on projects, while four mentors (the directors Annemarie Jacir, Ghassan Salhab, Karim Aïnouz, and Tala Hadid, all former DFI grant recipients) spent extended time with the young filmmakers, offering advice and encouragement. Of the works-in-progress, both Amin Sidi-Boumédiene’s Abou Leila, a drama set during the Algerian civil war about two friends who track a terrorist through the Saharan desert, and Hamid Issa’s Places of Soul, a personal-poetic documentary that links the landscapes of Antarctica and Qatar, hold considerable promise. Meanwhile, a number of picture-locked features, including an animated movie from India (Bombay Rose), a dark comedy from Morocco (The Unknown Saint), and the latest from Last Men in Aleppo director Feras Fayyad (The Cave), should be premiering on the festival circuit in the near future following this final round of consulting.

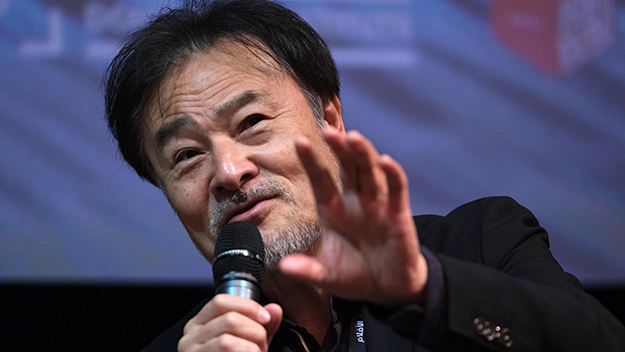

Kiyoshi Kurosawa at Qumra at the Museum of Islamic Art on March 19, 2019 in Doha, Qatar. (Photo by Tim P. Whitby/Getty Images for Doha Film Institute)

One of Qumra’s signature components is the Modern Masters program, a daily series of masterclasses with prominent directors and technicians. This year’s slate featured production designer Eugenio Caballero, along with directors Alice Rohrwacher, Pawel Pawlikowski, and Kiyoshi Kurosawa. At two-plus hours each, the conversations (moderated by either Richard Peña or Jean-Michel Frodon) flowed widely through each participant’s career, allowing ample discussion, for instance, of both Caballero’s award-winning work on Roma (2018) and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) and his less heralded designs for Fernando Eimbcke’s Club Sandwich (2013) and Jim Jarmusch’s The Limits of Control (2009). Caballero prefaced the discussion by stating that he considers production design to be a narrative rather than aesthetic discipline, and as he walked the audience through his filmography via video clips, design sketches, and on-set photos, it was easy to see how he’s put this philosophy into action with the help of his collaborators. Kurosawa also emphasized the collaborative nature of his practice, stretching from his early days as a Super-8 filmmaker to his time spent working in Japan’s V-Cinema (direct-to-video) industry. But it was Rohrwacher, the youngest of the “Masters,” who provided the most insight into both her background and the development of the medium. In between anecdotes about her early desire to join the circus, her first movie-going experiences, and the “extreme love” she shares with her sister, actress Alba Rohrwacher, she spoke of the productive limitations of working with celluloid (“When you don’t have options it’s easier to go farther”), the false narrative about the economic benefits of digital, and of cinema as a communal experience. To the latter point, when answering a question about Happy as Lazzaro’s U.S. release through Netflix, she stated that “the greatest emotion occurs in a cinema with an audience, as opposed to [through] streaming or VR.”

Photo by Eamonn M. McCormack/Getty Images for Doha Film Institute

Having just come from Qumra’s virtual reality exhibit earlier in the day, that final statement resonated with me. By now VR is an integral component of most major film festivals; it’s useless to resist its proliferation. Questions as to its utility and capacity as a storytelling medium, however, are far from settled. Addressing these concerns in an on-stage presentation, VR and interactive technology expert Michael Reilhac situated the medium in the context of a narrative tradition stretching back well before cinema. We as humans, he said, tell stories to make sense of our lives, to “create worlds we can master” and to “take revenge” on the mysteries of existence. Tracing contemporary cinema’s move toward immersive fiction in films such as Children of Men (2006), Son of Saul (2015), and Hardcore Henry (2015), Reilhac noted that while cinema inherently concerns itself with the temporal aspects of storytelling, VR is uniquely equipped to manipulate both time and space. Not withstanding Reilhac’s disregard for cinema’s imaginative dimension—the very thing that makes the medium so conducive to extrasensory experience—it was nonetheless interesting to learn of VR’s strides toward spatial-temporal coherence through interactive technologies. Indeed, if nothing else, recent advances in both finger haptics and “re-skinning” technology (in which the contours and dimensions of the real world are digitally mapped into the viewer’s virtual space) suggest that VR may soon be making good on some of its immense promise.

Spheres (Novelab, 2018)

As it stands, we’re some ways off. Qumra’s two VR experiences, the Novelab production Spheres and Penrose Studios’ Arden’s Wake: Tide’s Fall, each embodied both the appeal and limitations of room-scale VR. Executive produced by Darren Aronofsky, the three-part Spheres takes the viewer into outer space, where Millie Bobby Brown, Jessica Chastain, and Patti Smith (yes, that Patti Smith) narrate portentous tales of creation and the cosmos. In each, interactive moments arise in which the viewer is asked to swipe their Oculus Touch controllers to, say, dislodge a planet, trace the gravitational waves of a black hole, or summon a song from a distant moon. Accompanied by intergalactic synth music by S U R V I V E’s Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein (aka the guys behind the Stranger Things score), the piece unfolds with a grandiosity appropriate for its subject, though it’s studied tone and self-important presentation struck me mostly as educational, rather than entertaining. Spheres has been presented at numerous film festivals over the past year, and even picked up the Grand Prize in VR at Venice, but its attributes may in fact be best articulated in the classroom.

Arden’s Wake: Tide’s Fall (Penrose Studios, 2018)

For many, including this viewer, the real-world imagery of VR likewise still leaves something to be desired. Which may be why I had a better time with Arden’s Wake, an animated VR experience that makes no pretense at realism—at least visually. The story, about a motherless young girl (voiced by Alicia Vikander, who also executive produced) in search of her troubled father (Richard Armitage), who has disappeared while deep-sea diving, is surprisingly adult in its concerns, touching on abuse, alcoholism, and female autonomy. Forgoing an interactive component, the piece proceeds in a fairly straightforward manner; with no recourse to the narrative, the viewer is thus left to explore the seabound world however they please. Personally, I found myself walking around objects and structures, ducking under piers, and dipping under water to see how the atmosphere and sonics might change—and they did, pleasingly and, according to the logic of this world, rationally. Still, because of this freedom, it was tempting to ignore the story altogether. According to Reilhac, reconciling these impulses is one of the ongoing concerns of VR producers: on the one hand it’s what makes the medium unique; on the other it’s what can make the storytelling element feel inconsequential.

Where Qumra and the DFI fit into this evolution is hard to say. One DFI executive mentioned that they hope to soon fund a television project, and by that same token it’s easy to imagine them one day doing the same with VR. “Qumra without borders” is how the organizers phrased this year’s theme; a political statement, but a creative one as well.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival.