Deep Focus: A Private War

At its turbulent peak, A Private War movingly depicts Marie Colvin’s conflict reporting as an act of personal and moral witness. In this film, as in Marie Brenner’s terrific 2012 Vanity Fair piece, “Marie Colvin’s Private War,” everything she does is firsthand. Whether in Sri Lanka, Iraq, Libya, or Syria, she won’t allow anything or anyone to filter her connection to what she called “humanity in extremis.” She ignores government protocols and military strictures (no “embedding” for her), ditches political handlers, and charts her own paths straight into hearts of darkness. Believing “The Big Picture” can be misleading, she roots her stories in head-on and face-to-face perception. At odds with digital technology, she records facts and observations and composes rough drafts in long-hand, mirroring the practice of her journalistic ideal, Martha Gellhorn. The direct force of her fingers guiding pen over paper maintains her tactile commitment to reporting every step of the way, from sussing out a story to writing it.

A Private War plays down her ultra-competitive edge and emphasizes her crusader side: her attempts to choose subjects from the humanitarian emergencies at hand, resisting external pressures, including her editor’s blood pressure. The movie’s star, Rosamund Pike, and its first-time feature director, Matthew Heineman, who made the immersive documentaries Cartel Land (2015) and City of Ghosts (2017), bring the field aspects of this legendary correspondent’s life a total Colvin-like commitment. Pike flawlessly adopts her svelte yet rugged physicality as well as what Brenner calls the London-based expat’s “American whiskey tone.” (Colvin grew up in middle-class East Norwich, Long Island, adjacent to Oyster Bay.)

More important, via some kind of thespian alchemy, Pike thoroughly assumes Colvin’s forthright yet sensitive style and sensibility. A Private War is promiscuous with quotations from the journalist’s own wit and wisdom. Pike’s intelligence and offhand fervor manage to make even the biggest verbal stretches feel organic, whether she’s snarking that “they don’t make men like they used to,” elegizing the “quiet bravery of civilians,” quipping about how “stupid I would feel writing a column about the dinner party I went to last night,” or invoking Gellhorn’s “Never believe governments, not any of them, not a word they say.”

Of course, the transplanted words work best when they’re embedded in the action. In Sri Lanka, for example, her voiceover notes that the second-in-command of the rebel Tamil Tigers carries a “walking stick” that’s “a legacy of the three times he was shot in battle since joining the founding ranks of one of the most ruthless guerrilla movements in the world.” With laser-targeted empathy, Pike’s Colvin trains her eyes—or, after a calamitous error in Sri Lanka, her eye—on war-wounded and/or displaced people. Her direct questions and almost tangible responsiveness leave them no room for embarrassment. But with the deadly and incongruously campy Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi (Raad Rawi, in a shrewd, funny performance), she’s fiercely confrontational. She plays him just right, and, creepily, he loves her for it.

Heineman has skillfully documented global trouble spots such as the cartel-dominated state of Michoacán, Mexico in Cartel Land, and the war-ravaged Syrian city Raqqa in City of Ghosts. Here he establishes himself as a master at capturing the heightened sensations and hair-trigger reactions of men and women caught in crises. He knows how to position the camera so that we comprehend what occurs in murky, jeopardy-filled situations, then experience the ensuing attacks as if they’re happening to us.

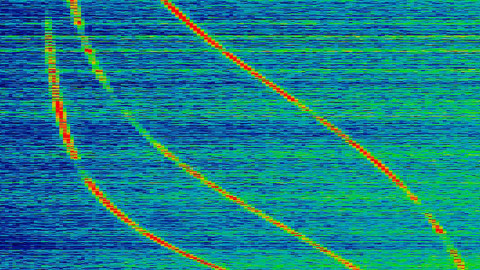

We share Colvin’s revelations in 2001, when she becomes the first foreign journalist to visit the Tamil-held territories of Sri Lanka in six years, exposing (as she wrote) “a huge but unreported humanitarian disaster for the 500,000 civilians who live here.” And we’re right with her as she tries to exit with civilian guides. She strides down the side of a cashew plantation when flares from a Sri Lankan base light her up. She makes the split-second but unfortunate decision to stand in an open field and proclaim herself a “Journalist!” Heineman has staged, timed, and edited her movements so that her reflexes nearly become our own (without any ostentatious shots). When the shrapnel from a rocket-propelled grenade pierces her left eye and a lung, the impact is devastating—as if we feel it without mediation. This episode’s power also derives from the way Heineman and his magnificent cinematographer, Robert Richardson, lay out the scene. We sense Colvin’s vulnerability even when she walks in nocturnal shade. She steps away from a dark block of hedge or forest into bursts of enemy light that set our spines tingling. Later, from Colvin’s perch on a hotel rooftop, Heineman and Richardson evoke the quiet, spectral nights of the Libyan city Misrata, targeted by Gaddafi, in its own way as eerie as their vision of the Syrian-rebel city Homs after it has been gutted by Assad.

Still, not even their multiple achievements, or Pike’s, compensate for Arash Amel’s awkward and often inadequate script. Heineman must share in the blame for a relentless parade of missteps, starting with the decision to frame the movie abstractly with the camera pulling up from Homs as Colvin delivers a statement of journalistic principles. Every ensuing episode begins with a time-stamped legend—say, “London, 11 years before Homs”—so even viewers who don’t know Colvin’s story will feel the film as a countdown to her demise. Given that Pike is a fresh-faced 39, capable of playing even younger, it’s perverse to have limited it to Colvin’s life from 45-56, commencing with Sri Lanka and the loss of her eye. There would be more tragicomic dimension if we had seen her in all her youthful competitiveness and abandon. Brenner reports that even in Homs, she exulted to her editor, “No other Brits here.” Heineman is too clear-headed and hot-blooded a filmmaker to make his film holier-than-thou, but sometimes it is holier than she.

The title refers to Colvin’s struggle to accept the diagnosis and treatment of PTSD and various addictions: alcohol, cigarettes, action. (One of Brenner’s sources told her that Colvin used the identification of her PTSD as an excuse to avoid confronting her drinking problem.) Heineman renders her PTSD flashbacks in showy, disorienting montages that are, sadly, epiphany-free zones. And when Colvin checks herself into a hospital, she appears to be getting a restful psychoanalysis. When her trusty photographer Paul Conroy (Jamie Dornan) comes for a visit, she offers a ludicrous recitation of her mental ailments, topped by unresolved conflicts with her father, who couldn’t accept her taking stands of her own, and her mother, who couldn’t understand her unconventional life. Colvin’s labeling this confession “psychobabble” doesn’t make it any less psycho-babbly.

Dornan gives a refreshingly warm and sane performance. There’s some tangy comedy to the scenes between Colvin and a couple of composite boyfriends, Greg Wise as a semi-suave academic writing a novel about naval warfare and Stanley Tucci as a zesty millionaire who would never call his flings “one-night stands”: they’re always “sexual adventures.” (In my favorite exchange, the rich fellow asks her where she got her eye-patch, and she replies, “Treasure Island.”) But the romantic scenes simply fill in a central part of her life (her love of men); she doesn’t get to the bottom of things with either of them. Nor is there any clarity to her relationship with the London Times’s foreign editor, Sean Ryan (Tom Hollander), who appears to coddle, exploit, flatter, and insult her in turn. The overall point must be that Colvin could manage life on the road even when London was a morass for her. Mostly we feel that the moviemakers are in control only when she’s navigating war zones.

That’s not a fatal flaw. Heineman handles certain incidents in A Private War with such a rare combination of delicacy and power that they set off unexpected reverberations. Before the mobilizing American-led coalition advances into Iraq for “Operation Iraqi Freedom,” Colvin gets a lead on a mass grave and talks herself and her team past one of Saddam’s checkpoints, pretending that her London Health insurance card is a medical aid-worker’s ID. As an excavator digs up the site, families who believe the remains of loved ones will be found there gather round. A local man challenges their authority as the scene threatens to descend into bedlam. Once the first skull is unearthed, Colvin succeeds in urging him to respect the dead. The musique concrète of the digging machine merges with the black-clad female mourners’ keening.

As the shrouded skeletons accumulate, horror and grief mingle on Colvin’s and Conroy’s faces. We in the audience share their despair down to our bones. Colvin once summarized the ultimate challenge of her missions this way: “The real difficulty is having enough faith in humanity that someone will care.” A Private War is such a testament of faith.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and a contributor to the Criterion Collection.