Deep Focus: Honey Boy

Images from Honey Boy (Alma Har’el, 2019)

Shia LaBeouf, who peaked commercially in three Transformer films and hit a creative pinnacle as John McEnroe in Borg and McEnroe (2018), has written a raw, brilliant script for Honey Boy. This fictionalized cinematic memoir is unabashed “drama therapy”: it grew out of LaBeouf’s writings in rehab after ranting at police while on location for another film in Savannah, Georgia.

Whether or not it works as therapy, Honey Boy is a wonderful movie, directed confidently and intuitively by documentary-maker Alma Har’el in her first fictional feature. With emotion-charged transitions and elisions, Har’el glides between overgrown, self-destructive Otis Lort (Lucas Hedges), locked into denying his domestic PTSD, and precocious, high-achieving Otis (Noah Jupe), the child actor on the rise who pays his father James (played by LaBeouf himself), a recovering alcoholic/addict, to be his chaperone. Har’el has beautifully braided present-tense action and flashbacks (and fantasies) into this portrait of the artist as an abused son.

When 22-year-old movie star Otis thanks his rehab supervisor Alec (Martin Starr) for telling him to unleash a primal scream, Alec, no dummy, asks Otis if he’s “sincere” or if he’s “acting.” Otis levels with him: “Both.” What other answer could such a super-intense performer give? Otis is the kind of actor who psychs himself up on the set of a giant, Transformers-like action movie but can’t come down from the high. He carries his thespian prowess like an invisible shield: When a policeman cuffs him off-set, Otis absurdly tells the cop that he’ll be sorry when he learns how good Otis is at what he does.

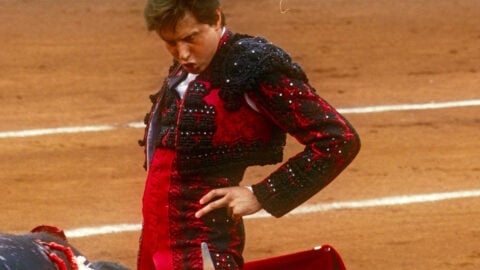

Otis’s father occupies the red-hot center of the psychodrama. LaBeouf frees himself of vanity as 45-year-old James, a Vietnam veteran who trained in Commedia dell’arte and entertained crowds as a rodeo clown. James now reads lines with his boy in his own insistent voice and modified New Orleans drawl and coaches him in slapstick farce. Otis appreciates James’s “instincts,” though the boy has been developing a better sense of what works for him comedically. The two have cobbled together a sort-of life between TV-sitcom studios and a seedy motel, where the courtyard is no garden and the neighbors across the way are hookers. While James has been clean for four years, he still can’t tamp down his temper at a 12-step meeting.

Noah Jupe and Shia LaBeouf in Honey Boy (Alma Har’el, 2019)

We may fear what he’ll do if he stumbles, since what he does when he’s sober is shocking enough. He’s so unsure of how to act like a father that he won’t hold his son’s hand: he’s afraid people will mistake him for a “chicken hawk.” He’s a registered sex offender because of an outrage he committed during an alcoholic black-out long ago. James is also ruinously jealous. It affronts him that his ex-wife enrolled Otis in the Big Brother program to acquaint him with a positive male role model. James can’t abide the weathered, benign presence of Tom (Clifton Collins Jr.), Otis’s Big Brother. But in one of the film’s many sly, expressive asides, we learn that Tom, a passport specialist for the State Department, would be happy to help the Lorts with their passports even after James curses him out and tosses him into the motel swimming pool.

At the movie’s volcanic core, James frustrates both 12-year-old Otis’s attempts to communicate with him son-to-father, and 22-year-old Otis’s struggle to reckon with his father’s legacy. (Otis has become an angry addict himself.) LaBeouf describes this film as an exorcism, but he molds and plays James with superb control, in ways that serve the story precisely. LaBeouf makes us believe that this troublesome dad has indeed turned his son into an artist, not merely because of the pain he caused, but also because of his passionate commitment to the boy’s creativity (and also, perhaps, his unconventionality). James tells Otis that his mom has gotten herself a job in case Otis fails as an actor: He insists that he’s Otis’s “cheerleader” as well as his physical trainer. When James teaches Otis how to juggle using balled-up pairs of socks, he makes him do ten pushups if he drops one.

For viewers to buy this film’s premise, there must be heft to James’s engaging silliness as well as his engulfing fury. And LaBeouf provides it, without going over the top. LaBeouf’s James tucks in his sizable paunch as he mounts his motorcycle and, on the road, covers his mouth with a raggedy bandanna. Wearing oversized circular glasses and a do-rag, he recalls rodeo routines he choreographed with an athletic chicken. As LaBeouf plays him, James is sometimes a human sight gag, sometimes a one-man counterculture. Despite his cruelty, we feel James’s agony when he confesses that it’s humiliating to draw a salary from his son. Otis is sadder and wiser and can be cruel himself: “You wouldn’t be here if I didn’t pay you,” the boy says.

Lucas Hedges in Honey Boy (Alma Har’el, 2019)

As movie-star Otis reluctantly grapples with his memories of childhood, Hedges masters shadow boxing: he must spar with LaBeouf’s James, who interacts with him only in flashbacks, nightmares, or reveries. Hedges is a wizard at conveying compacted, often boobytrapped emotions. It helps that Har’el surrounds him with such a smart ensemble. Martin Starr as his group leader Alec and Laura San Giacomo as his psychologist Dr. Moreno defuse his hardboiled skepticism toward therapy with unexpected patience, curiosity, and incisiveness. Byron Bowers provides a relaxed comic counterpoint as Percy, Otis’s roommate, who drifts into treatment as blissfully as he does into sleep. Alec jokes that Percy may be too good—by which he means, too happy—at hugging himself to release hormones. Bowers’s ultra-satisfied face provides the visual punch-line.

Even in this heady company, young Jupe gives the performance of the movie. He puts his character on a psychic tightrope and never misses a step. He gives Otis at age 12 the elan of a born star and a soulful artist’s face: sometimes his expressions betray baseline feelings; at other times they stress the drama playing out around him. He understands the conflicts between his father and mother (Natasha Lyonne, whom we do not see, just hear over the phone). He knows their fights will go on forever. In the most extraordinary scene, James refuses to get on the phone with his former spouse. Otis hangs on to the handset and relays each parent’s horrific condemnations to the other. Jupe delivers them like a pro.

Har’el and cinematographer Natasha Braier imbue the film with an empathetic lyricism. The exchanges between Otis and a young hooker referred to in the credits as “Shy Girl” (FKA twigs) redeem the whole notion of contemporary mime. The boy actor and Shy Girl seal their affection in a silent bit that combines elements of sorcery and softball. When they snuggle up in bed, they recover each other’s innocence, even after Otis does what he thinks he should do: he grabs some cash and pays her.

Har’el and Braier bring a gnarly shimmer to poolside dreams and roadside pipe-dreams. Along with LaBeouf, they bequeath the roughest characters with the tenderest mercies.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.