Cannes Report #4: Coppola, Kidman, and Women in the Industry

In a photo op this week at Cannes, Catherine Deneuve, Isabelle Huppert, Nicole Kidman, Jessica Chastain, and Juliette Binoche encircled jury president Pedro Almodóvar. An illustrious array of international cinema’s most famous faces were also there (including Agnès Varda, Jean-Pierre Léaud, Maren Ade, Kleber Mendonça Filho, Andrea Arnold, and Guillermo del Toro). But it was a photo from the red carpet later that day that got more attention, and which pointed to a persistent problem tarnishing this festival’s legacy.

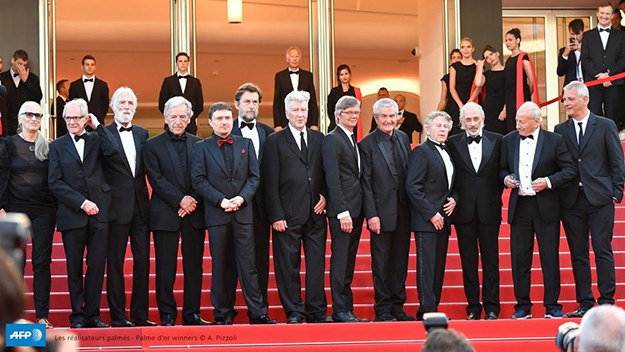

In the photo, 13 past Palme d’Or winners were gathered on the steps of the Cannes convention center. The image was striking. Ken Loach, Michael Haneke, Costa-Gavras, Cristian Mungiu, Nanni Moretti, David Lynch, Bille August, Claude Lelouch, Roman Polanski, Jerry Schatzberg, Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, and Laurent Cantet stood together, smiling for the cameras. However, in an unfortunate bit of stage management during the otherwise meticulously organized procession, Jane Campion, the only woman to ever win the Palme d’Or, was only visible at the far left of the sea of men.

Campion, here to premiere season two of her acclaimed series Top of the Lake, had bemoaned the dearth of women competing for prizes at Cannes when she was president of the jury three years ago. “I think you’d have to say there’s inherent sexism in the industry,” she said at the time. “It does seem very undemocratic. The guys seem to be eating all the cake.”

It’s a festival that has long weathered criticism for not including enough female directors in competition, which is widely considered the definitive showcase for international filmmakers. In the 18 editions since the turn of this decade, only 34 titles directed by women have played in the main competition. “I don’t select films because the film is directed by a man, a woman, white, black, young, old,” Cannes’s Artistic Director Thierry Frémaux told the Associated Press in 2012. “I select films because I think they deserve to be in [the] selection.” A few years later, he softened his stance. In 2015, the year the festival launched a new initiative for female filmmakers called Women in Motion, he said, “We at the festival are very happy that this debate has been started.” (Nevertheless, that year the festival came under fire when many women were denied entrance to the Palais because they weren’t wearing high heels—Frémaux blamed overzealous security guards.)

Elle Fanning, Nicole Kidman, and Sofia Coppola at The Beguiled press conference. Photo by Eugene Hernandez

Like last year, the 2017 edition features just three films by women in competition. One of them, Sofia Coppola’s The Beguiled, premiered on Wednesday. A new interpretation of Thomas Cullinan’s 1966 Southern Gothic novel, previously brought to the screen by Don Siegel in 1971, the Civil War–set tale follows a union soldier found behind confederate lines in Mississippi and taken in by an all-girls boarding school. In Siegel’s film, starring Clint Eastwood and Geraldine Page, the story is told from the perspective of the sole male character. Coppola said at a Cannes press conference on Wednesday: “I wanted to go back to the story and tell my own version. The essence of it is feminine.”

Coppola was initially resistant to the notion of remaking a movie. Yet after reading the original source material, upon production designer Ann Ross’s insistence, she was intrigued. She says she didn’t even bother to watch the 1971 film.

“This story had to be directed by a woman,” offered Nicole Kidman, seated near Coppola. Kidman stars as the school’s matron, the role once played by Page. And Colin Farrell takes on the only male part in The Beguiled, a character who is brought back from near death thanks to the women’s care. As he heals, they are intrigued and aroused by his presence.

Kidman, who has four films at Cannes this year, has been outspoken about the importance of women behind the camera. She said, “We as women have to support female directors. Hopefully that will change over time. People keep saying it’s so different. It isn’t, so listen to that.” She highlighted recent statistics that only 4 percent of major motion pictures were directed by females last year, and she reported that of 4,000 episodic series, only 183 were directed by women. “We need stories,” she added. “We need the opportunities.”

A study reported by The New York Times on the opening day of Cannes found that film festivals are a particularly problematic segment of the industry in terms of female representation. The survey, done by the Center for the Study of Women in Television & Film at San Diego State University, focused on 23 leading American festivals over the past year.

Findings from the study revealed that high-profile film festivals screened three times as many narrative films and almost twice as many documentaries directed by men than by women; plus, more than twice as many men were employed in key behind-the-scenes roles in independent films screened at the same festivals. Meanwhile, the number of female directors in independent films went up slightly from 28 percent in 2015-16 to 29 percent in 2016-17, which was an increase of seven percent from 2008-09.

Because many festivals look to the programming of premier fests like Cannes and Sundance to set their own slates, the data reveals an ongoing challenge. If films by women aren’t screened in Cannes in May or Park City in January, it’s much less likely that other festivals will make progress. The lack of films by females in festivals is seen as an indicator of the lack of support for movies made by women in all areas of the industry, from Hollywood to independent to art-house.

[Note: Festivals surveyed included the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s New York Film Festival as well as New Directors/New Films, a joint effort with the Museum of Modern Art. The Film Society is the publisher of Film Comment.]