Moral Necessity: Amos Vogel in Film Comment

This article appeared in the November 11 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

Film Comment, May-June 1975

This fall saw the veneration of Amos Vogel in numerous tributes honoring his astounding achievements—particularly Cinema 16, the New York Film Festival, and Film as a Subversive Art. The dozens of lovingly organized screenings of some of the hundreds of films Vogel programmed, championed, taught, or wrote about, with thousands more waiting their turn, have revealed that however much one may know of his work, there was more—always more.

Following the publication of Film as a Subversive Art in 1974, Amos Vogel continued to make his enthusiasms public in the pages of Film Comment, along with frustrations and wrongs he deemed a “moral necessity” to make right. The majority of Vogel’s writing for the magazine appeared in a column titled “Independents” (initially “Independent Film”). The name indicated the myriad forms of film art, film culture, and film politics that could be gathered under one (non-commercial) banner, and the column encompassed a wide variety of topics which are now all too frequently relegated to a specific area of coverage. Vogel wrote about topics familiar to readers of film magazines, such as surveys of festivals (most often the Berlinale), book reviews, and obits. But he also found space for a pissed-off report on the terrible state of theater-going in the January-February 1981 issue, which charmingly includes a reference to the ancient format of reduction prints. And in January-February 1980, he mentions AFI’s “Set Sail with the Stars” cruise, which Vogel lamented missing, considering King Vidor was aboard (!!).

Vogel’s passion was for highlighting anything he found worthy of interest and praise, wherever he found it: Manhattan Public Access, specifically Dee Dee Halick’s extraordinary Newspaper Tiger Television Productions: Smashing the Myths About the Information Industry; magazines and journals, including St. Clair Bourne’s Chamba Notes, Jackie Raynal’s The Thousand Eyes, and Pittsburgh Filmmakers’ Field of Vision. Vogel applauded programmers (Karen Cooper, Fabiano Canosa, David Bienstock), venues (Collective for Living Cinema, Millenium), series (MoMA’s Cineprobe), workshops and production studios (Global Village), and the New York Public Library’s beloved Donnell Library Center.

Vogel’s explorations took him to symposia for International Women Filmmakers and the International Computer FilmConference, where, he reported in a July-August 1974 column, “…those present (not the New York film critics) were given the privilege of witnessing the mysterious, awesome emergence of a new tendency in film art…” He also attended the first U.S. Conference for an Alternative Cinema at Bard College, an event with “close to 500 left-wing media activists” (November-December 1979). Vogel helpfully blesses us with the names of nearly every individual and organization who participated in the event, providing the reader, then as now, with endless avenues for further research and exploration.

Ultimately, “Independents” is a convergence of Vogel’s advocacy for film art and his insistence on addressing cultural and political hypocrisies. The majority of the columns are, in simplest terms, an extension of Film as a Subversive Art. With a few perfectly deployed words, Vogel convinces readers that an extraordinary film would have been comfortably at home in an updated edition of his book. Of Thierry Zéno’s Des morts or Of the Dead (1979), a work confronting the taboo of filming death, he writes in the March-April 1980 issue that it is, “A film that must be shown at New York Film Festival and never will be.” His corrective impulses are on display in a January-February 1975 column featuring a lacerating denunciation of the “…rapidly emerging new Leni Reifenstahl myth (in America, not Europe where they know better), according to which she is not merely a great filmmaker (a fact on which all are agreed) but only made innocuous, ‘factual’ ‘documentaries,’ with neither the films nor the filmmaker organically related to Nazism . . . assiduously abetted by the most unlikely combination of rightist, leftist, and politically innocent/ignorant forces…”

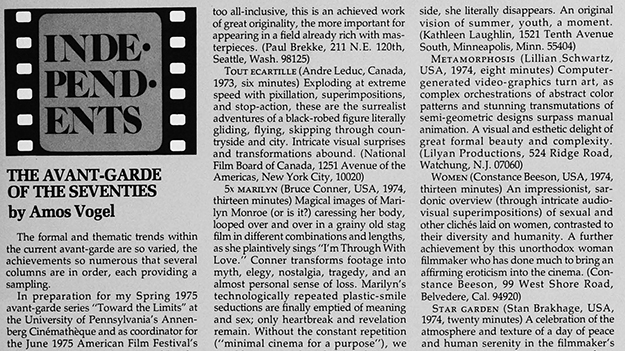

Vogel provides dozens upon dozens of programming and viewing recommendations, always helpfully supplemented by contact names, addresses, and rental costs. He wrote about filmmakers far beyond the period of their semi-popular consideration by critics and admonished the scarcity of distributed work from directors he had highlighted a decade earlier in his book. On Philippe Garrel in the July-August 1983 issue: “It is one of the not-so-secret scandals of film history that Garrel’s oeuvre (particularly Le Revelateur, Le lit de la vierge, Concentration, La cicatrice interieure) is not known in America.” “Independents” was also a means of keeping up with new work and subjects of enduring relevance, with Vogel dedicating entire columns to a single film he was ecstatic about (like Suzan Pitts’s Asparagus in the May-June 1981 issue), or to films and resources on the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to ensure it does not fall out of consciousness (January-February 1983). In the latter, he writes of an image of a bombing victim, “Will she stir us to action—or shall we remain frozen in impotent gestures of pity and remorse, of watching and writing about films?”

Consistently, his columns argued against the common critical insistence on categories. In the four-part “A Reader’s Digest of the Avant-Garde,” which began in the July-August 1976 issue, Vogel railed against accepted definitions of the avant-garde that excluded, dismissed, or deliberately overlooked the varied and undefinable forms of experimental films: “One is impressed with the truly spectacular nerve with which entire historical periods, events, and institutions have been collapsed into magnificent reductive fantasy. This is not history but metaphysics—the forced unearthing of a non-existing pattern based on prior bias.”

Taken together, Vogel’s writing in Film Comment evidences his incomparable discernment and insight. “Independents” is a practical instruction guide and up-to-the-minute resource list for adventurous programmers and engaged viewers, as well as an unending source of marvel and a dose of humility. The study of cinema was the vehicle Vogel chose to manifest his thinking. His writing draws us closer in a shared passion (even as he practices a more rigorous mode of appreciation that anyone could hope for), inspiring us to continue to push back against established and accepted forms of wisdom and power.

“Thereafter having attempted to clean up the past—this column returns to the untidy present.” – November-December 1976

“More to come.” – May-June 1975

Thanks to Mackenzie Lukenbill for archival assistance.

Jake Perlin is a film distributor and publisher (Film Desk and Film Desk Books) and the founding Artistic Director of Metrograph.