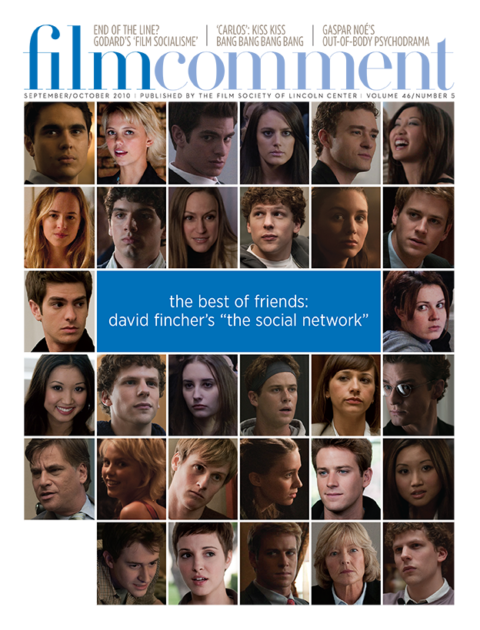

By Scott Foundas in the September-October 2010 Issue

Revenge of the Nerd

The misanthropic soul at the heart of David Fincher’s 21st-century moral tale

It was E.M. Forster, of course, who scripted that immortal, oft-abbreviated imperative: “Only connect, and the beast and the monk, robbed of the isolation that is life to either, will die.” But had Forster lived to see the advent of something like the Internet, would he have been so quick to admonish the life bestial or monastic? As I write this, I am not nor have I ever been a member of those ubiquitous online communities known as Facebook and Twitter, which have separately and together transformed millions of us into the stars of our own reality shows, complete with “friends” and “followers” tuned into our every banal thought or change of mood, and where human popularity is tabulated in numbers as readily as the weekly box-office returns. In my Luddite way, I harbor a healthy suspicion for any technology whose adopters seem more its slaves than its masters. Above all, I cling foolhardily to the belief that the more time-honored methods of human interaction maintain a slight edge over the electronic ones. Indeed, though we may now live in public, we seem to see rather less of one another.

From the September-October 2010 Issue

Also in this issue

On the other hand, half a billion people can’t be wrong—or, rather, they can, but good luck convincing them of it. A scant seven years into its existence, Facebook is already an inevitability, a cultural axiom. Among other things, it is said to have played a role in rallying America’s youth for the 2008 election (even if some of those youths were actually the fictitious avatars of middle-aged men and women seeking a little masked-ball escapism, or something more sinister). Nor is its reach limited to these shores: recently, Facebook was banned in Pakistan for supposed trespasses against Islam, which is no small achievement for a website that traces its origins back to an Ivy League social misfit’s drunken act of revenge against a girl who spurned him. Like so many historic achievements in arts, letters, and commerce, Facebook was born of a romantic rejection.

This is very rich material for a movie on such timeless subjects as power and privilege, and such intrinsically 21st-century ones as the migration of society itself from the real to the virtual sphere—and David Fincher’s The Social Network is big and brash and brilliant enough to encompass them all. It is nominally the story of the founding of Facebook, yes, and how something that began among friends quickly descended into acrimony and litigation once billions of dollars were at stake. But just as All the President’s Men—a seminal film for Fincher and a huge influence on his Zodiac—was less interested by the Watergate case than by its zeitgeist-altering ripples, so too is The Social Network devoted to larger patterns of meaning. It is a movie that sees how any social microcosm, if viewed from the proper angle, is no different from another—thus the seemingly hermetic codes of Harvard University become the foundation for a global online community that is itself but a reflection of the all-encompassing high-school cafeteria from which we can never escape. And it owes something to The Great Gatsby, too, in its portrait of a self-made outsider marking his territory in the WASP jungle.

Adapted by The West Wing creator Aaron Sorkin from Ben Mezrich’s nonfiction best-seller The Accidental Billionaires, The Social Network was one of those “buzz” scripts that seemed to be on everyone’s lips in Hollywood for the past couple of years, and it’s easy to understand why. The writing is razor-sharp and rarely makes a wrong step, compressing a time-shifting, multi-character narrative into two lean hours, and, perhaps most impressively, digests its big ideas into the kind of rapid-fire yet plausible dialogue that sounds like what hyper computer geeks might actually say (or at least wish they did): Quentin Tarantino crossed with Bill Gates.

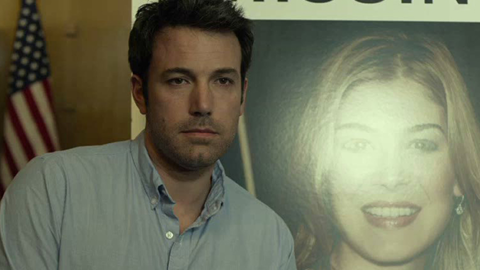

Consider the movie’s opening—a soon-to-be-classic breakup scene in which soon-to-be Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) verbally machine-guns his soon-to-be ex-girlfriend Erica (Rooney Mara) with a rant about the difficulty of distinguishing oneself “in a crowd of people who all got 1600 on their SATs.” From there it’s on to his conflicted feelings about that peculiar Harvard institution known as “final clubs,” elite secret societies that, sops to diversity notwithstanding, remain decidedly inhospitable to monomaniacal, borderline Asperger’s cases like Zuckerberg. As he holds forth, his face contorted into a tightly focused stare, looking through Erica rather than at her, she tries to keep up. “Dating you is like dating a Stairmaster,” she laments before delivering the delicious coup de grace: “Listen. You’re going to be successful and rich, but you’re going to go through life thinking that girls don’t like you because you’re a geek. And I want you to know, from the bottom of my heart, that that won’t be true. It’ll be because you’re an asshole.”

It was that rejection, or one like it—the details aren’t specified in Mezrich’s book—that led to an infamous late-night (and inebriated) programming session during which Zuckerberg created a crude comparison website allowing Harvard students to rank the relative desirability of the university’s female population based on photos hacked from the student directories (or “facebooks”) of various dorms. Soon, Zuckerberg’s prank went viral across the campus, making him a pariah to his female classmates, earning him academic probation, and bringing him to the attention of a trio of undergraduate entrepreneurs: the Indian-American Divya Narendra (Max Minghella) and the towering, blond and bronzed identical twins Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss (both played by the disarming Armie Hammer, himself a scion of corporate blue bloods). In between their rigorous course loads and heavy training regimen for the Harvard crew team, the Winklevoss brothers had conceived of a dating website open only to those who possess a Harvard e-mail address (the rationale being, quite simply, “Girls want to go with guys who go to Harvard”) and needed someone to design it for them. And Zuckerberg, as he would surely regret doing later, accepted the assignment.

The rest of The Social Network runs along two parallel narrative tracks—one tracing Zuckerberg’s development of Facebook and the other detailing the lawsuits later filed against him by the Winklevosses and by former Facebook CFO Eduardo Saverin (the superb Andrew Garfield), the latter being the closest thing in the movie to a wholly sympathetic character. From a legal perspective, it’s a thorny case of he-said/he-said, though the movie is less concerned with assigning blame than with considering Zuckerberg’s precise degree of assholedom, or lack thereof. And this is where things really get interesting. It would be easy enough, of course, to vilify Zuckerberg as a greedy twerp who betrayed his friends (what few he had) and partners on his way to the top—we are, after all, talking about a 24-year-old billionaire who once carried business cards reading “I’m CEO . . . bitch.” It would be even easier, perhaps, to exalt him as a nonconformist deity, a Holden Caulfield of the information superhighway. But to the sure nervousness of the studio, and the potential discomfort of some viewers, Fincher and Sorkin chart a more treacherous course straight down the middle of Zuckerberg’s many contradictions, one in which there are no obvious winners or losers, good guys or bad—only a series of highly pressurized social (and genetic) forces.

“I’m six-foot-five, 220, and there’s two of me,” notes one of the Winklevoss brothers upon learning of Zuckerberg’s Facebook subterfuge, contemplating physical retaliation—and indeed, one of the movie’s great visual gags is the recurring image of these two Aryan gods seated across the deposition room from the pale, slight Zuckerberg in his signature hoodie and “fuck-you flip-flops.” Yet at the same time, it’s hard not to see plaintiff and defendants as opposite sides of the same ambitious coin: gifted young men driven to separate themselves from the herd, two by moving to the front of the pack and one by going upstream against the current. Time and again the point is made that Zuckerberg doesn’t lust after riches, having turned down lucrative offers from Microsoft and AOL while he was still in high school (to buy another software program he designed), but status is something else entirely. “They’re suing me because for the first time in their lives, things didn’t work out the way they were supposed to for them,” Zuckerberg notes at one point—oblivious to the fact that he’s making himself sound equally petty. This leads to another of the movie’s most revealing scenes, in which a young legal associate (Rashida Jones) schooled in the fine art of jury selection advises Mark to settle out of court rather than face a jury destined to judge him on such factors as “clothes, hair, speaking style” and, above all, “likeability.” “Myths need a devil,” she reminds, and Zuckerberg fits the bill. Whereas the “Winklevi”—well, they could probably get away with murder.

Lest I seem to suggest otherwise, I hasten to add that The Social Network is splendid entertainment from a master storyteller, packed with energetic incident and surprising performances (not least from Justin Timberlake as Napster founder Sean Parker, who’s like Zuckerberg’s flamboyant, West Coast id). It is a movie of people typing in front of computer screens and talking in rooms that is as suspenseful as any more obvious thriller. But this is also social commentary so perceptive that it may be regarded by future generations the way we now look to Gatsby for its acute distillation of Jazz Age decadence. There is, in all of Fincher’s work, an outsider’s restlessness that chafes at the intractable rules of “polite” society and naturally aligns itself with characters like the journalist refusing to abandon the case in Zodiac and Edward Norton’s modern-day Dr. Jekyll in Fight Club. (It is also, I would argue, what makes the undying-love mawkishness of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button seem particularly insincere.) So The Social Network offers a despairing snapshot of society at the dawn of the 21st century, so advanced, so “connected,” yet so closed and constrained by all the centuries-old prejudices and preconceptions about how our heroes and villains are supposed to look, sound, and act. For Mark Zuckerberg has arrived, and yet still seems unsettled and out of place (as anyone who witnessed his painfully awkward 60 Minutes interview two years back can attest). And now here is a movie made to remind us that nothing in this life can turn a Zuckerberg into a Winklevoss.