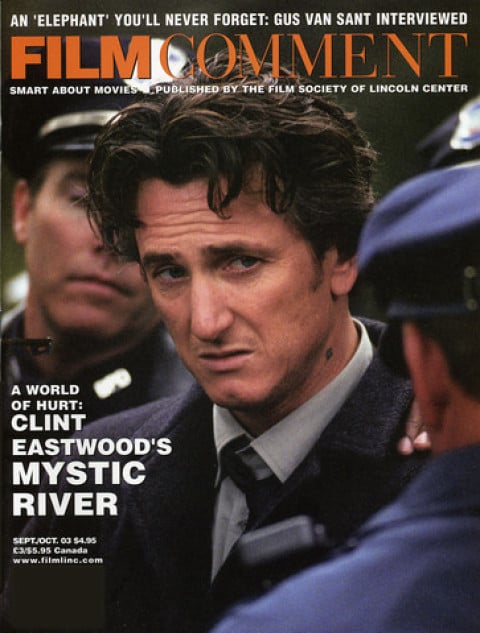

By Richard Combs in the September-October 2003 Issue

The Poetics of Resistance

Considering the Ozu behind “Our Ozu” on the occasion of the Japanese director’s centennial

Is Yasujiro Ozu unique among major filmmakers in that his name conjures up such a definable and clear-cut image of his work, while his filmic personality and stylistic history, through a 35-year career and some 53 films, slides away somewhere behind it? To spare the effort of looking for a comparable case, we can construct one: imagine that John Ford’s films from The Informer through Stagecoach, The Grapes of Wrath, and My Darling Clementine, had largely dropped from the historical memory, had somehow been rendered redundant by his development from, say, The Searchers through The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Donovan’s Reef to 7 Women.

From the September-October 2003 Issue

Also in this issue

Late Ozu is “our” Ozu (possibly infringed upon only by the 1932 comedy I Was Born, But . . .), the succession of family dramas with seasonal titles, from Late Spring in 1949 to An Autumn Afternoon in 1962, films in which plotlines are diffused through quotidian detail and the dramatic highlights are either elided or undramatically tidied away. These are films in which “nothing happens” but where matters of life and death, the weight of the past and the terror of the future, are dealt with, and anger, disappointment, despair, and resignation are also accommodated.

Not that earlier Ozu has exactly been consigned to oblivion. Commentators as diverse as Donald Richie and David Bordwell have kept the entire oeuvre in view (Bordwell’s 1988 Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema is dauntingly comprehensive), and Noel Burch (in To the Distant Observer) provides a theoretical account that claims the late silent and early sound period as Ozu’s most experimental and throws out “our” Ozu as a steady calcification. The remarkable imposition of the Ozu “image” beginning in 1949 depends on a narrow range of subject and theme, worked through a comparably narrow range of stylistic choices—choices made from the common pool of classical or mainstream movie techniques.

Tokyo Story

The image imposes itself so forcefully mainly because it doesn’t seem to manifest any idiosyncratic “authorial” authority. Its means are selected from the prescribed methodologies, but it is then rendered unique by the unnaturally high degree of selectivity and the idiosyncratic combinations into which the choices fall. It’s as if the narrowing process leads inevitably to some vanishing point of the individual artwork and cinema’s industrial norms. In such vanishing is the perfection and preservation of this Ozu image.

To be sure, our Ozu will be put in perspective by the 34 films to be shown in the retrospective at this year’s New York Film Festival, and in other programs set for this centennial year. But context apart, are there other ways of picturing Ozu that might in a sense break up the image, by revealing new lines of force, bringing a different dynamic into play?

One starting point might be a potent line of dialogue in Tokyo Story (53), toward the end of the Hirayamas’ visit to their grown children in Tokyo. The problems of accommodating the elderly couple have finally led to their being split up, and while father Shukishi (Chishu Ryu) is out drinking with old buddies, mother Tomi (Chieko Higashiyama) is put up in the small apartment of her widowed daughter-in-law, Noriko (Setsuko Hara). The latter’s husband, the Hirayamas’ eldest son, Shoji, is missing, presumably killed in the war. His photograph is still prominently displayed, and as she is settling down for the night, Tomi sighs, “How nice to lie in my dead son’s bed.”

Tokyo Story

This could be taken as one of a number of premonitions that have begun to build up around Tomi, to be expressed by her (watching her grandson play earlier, she muses, “By the time you’re a doctor, I wonder where I’ll be?”), about the unsuspected illness that will put her in a terminal coma soon after she returns home. Or it could be that families will always keep their dead and missing close. “I’m forgetful, yet I remember things about Shoji,” says Chieko Higashiyama, the same actress but as a different mother in a different film, Early Summer (51), talking about a different Shoji, also missing in the war. Father believes he must be dead, but mother continues to hope and listens to a radio program called “The Missing Persons Hour,” a kind of doubling of his ghostliness.

And if Tomi in Tokyo Story can slip into her son’s place, father Shukishi already stands more ambivalently, troublingly, behind it. “Did Shoji drink?”, Tomi asks her daughter-in-law at one point during their reminiscences, and when told that he did, she sympathizes, “So you had the sort of trouble I did.” Shukishi admits to his old friends, “I’ve always disgraced myself by drinking,” before going out on a bender that will lead to the film’s most comic scene. In the dead of night, Shukishi and a similarly incapacitated friend will be delivered by the police to the premises—home and hairdressing salon combined—of his discomfited daughter Shige (Haruko Sugimura), who has been most irritated throughout by the old folks’ visit, and dropped into her hairdressing chairs to sleep it off.

The like-father-like-son comments might be an aside, if they didn’t shade what is ostensibly the main concern of the film: the drifting apart of the generations, the disappointment of the parents both in what the children have achieved for themselves and what they’re prepared to extend to their parents, the changes that time and modern life bring. What is suggested instead is that the drifting apart is illusory, that alongside ties of guilt and responsibility there will always be a slip-sliding between characters, a substituting and making up, in whole or part, because loss, incompleteness, and insubstantiality are also part of the passage of time. In the bar scene where Shukishi gets drunk with his two friends, it’s an almost de rigueur Ozu moment that one of the men will declare, as the evening goes on, that the bar girl more and more resembles his departed wife. It’s an effect that also overtakes the mild but quite steady drinker Shuhei Hirayama (Ryu) when he’s introduced to Tory’s bar in An Autumn Afternoon. He even takes his elder son, Koichi, along to confirm the resemblance, but the latter can’t see it. This might explain the remarkable predominance of widowers in Ozu’s later films, which doesn’t have to do with the life expectancies of men and women in Japan but with the need to set these men adrift to find substitutes (or imagined substitutes) for their missing loved ones—though it’s a ribald joke in An Autumn Afternoon that one of the three friends simply finds it in a younger wife.

An Autumn Afternoon

But the fulcrum of this in Tokyo Story is not any of the blood relatives of the Hirayama family—with their ambivalent, guilty, recriminatory ties that bind—but the partial outsider Noriko. She is identified with Shoji but is now necessarily adrift from him (“Often I don’t think of him for days”); she is more considerate and obliging toward her in-laws than their own children are, but can confess, “I’m quite a selfish person, actually.” Their pleas that she should remarry seem to fall on deaf ears: “My heart seems to be waiting. . . . Sometimes I feel I can’t go on like this forever.” Which picks up on the dark hint she leaves when Tomi warns her that she’ll feel lonely as she grows older: “I’ll never be that old, don’t worry.”

In Early Summer, Setsuko Hara’s Noriko again has a pulling-away quality, whether because she’s a new woman (“It’s not that I can’t—I won’t,” she says in response to family pressures to marry) or just contrary. The man she finally elects to marry—against her family’s angry protestations—is a widower with a child, a doctor colleague of her brother’s about to be posted away from Tokyo. “That’s what made me decide,” she says, although she also worries that in the process she is breaking up the family. There’s even her boss’s remark, when a friend comments that Noriko used to collect photographs of Katharine Hepburn: “A woman? Is she that way?” (It’s hard to recall the question of sexual compatibility, let alone preference, being raised in all the discussions around Ozu marriages.) And for all her kindness and consideration, Noriko (here and in Tokyo Story) has a habit of being late.

Her persona in the Japanese cinema earned Setsuko Hara the sobriquet of the “perennial virgin,” which is not exactly the kind of “holding out” she displays in Tokyo Story and Early Summer. Though perhaps, for all its connotations of Doris Day-ness, the tag hints at the secretiveness along with the sweetness, the wryness, and the apologetic perversity (which seems to come from not quite knowing herself) of her Norikos. Chishu Ryu, with roles through nearly all of Ozu’s output, may be the holding center of his cinema, his alter ego on film, Ryu’s sorrowful detachment at the close of Tokyo Story allowing it to support interpretations of Buddhist serenity and transcendence. But the performances of Setsuko Hara may be closer to whatever is secretive, wry, and resistant in Ozu himself. There’s a film with Hara that Ozu didn’t make—although in some way he may have—called I Married, But . . .

I Flunked, But . . .

He certainly found the “I, but . . .” construction (evidently a popular catchphrase of the time) appealing enough to use it three times: I Graduated, But . . . (29), I Flunked, But . . . (30), and I Was Born, But . . . It’s interesting to speculate about what he was resisting, or what appealed about this equivocation, this going-back-on-itself self-assertion, since in terms of his working life he was so famously and unusually well adjusted. Partly this explains that narrowing to a vanishing point of late Ozu, because he was a happy house director working with the stylistic rigor of Carl Dreyer. His first film, Sword of Penitence (27), was made for Shochiku Studio, as was his last, An Autumn Afternoon. The few exceptions in between—for example, Floating Weeds (59) at Daiei; The End of Summer (61) at Toho—were not signs of periodic estrangement or rebellion, just that he had fulfilled his Shochiku contract in those years.

But if not rebellion, there was a persistent pulling back, a turning aside from certain options, or a tendency to approach matters of both dramatic craft and technological innovation in a roundabout way, so that the teasing delay, the development left in suspension, becomes part of the texture of his films. Most striking of Ozu’s delays was the fact that he took until 1936 to make his first full sound film, The Only Son. But Donald Richie has traced Ozu’s refusals back even to his reluctance to accept promotion from assistant director: “Early, Ozu became known around the studio as the man who says no. He said no to becoming full director. Later he said no to a number of scripts. Now he was saying no to his actors, making them work harder than they had ever had before. Later, he would refuse to make talkies—for a time. He would eventually refuse to make more than one film a year. Still later, he would refuse color, to succumb eventually. He never did accept widescreen.”

And eventual acceptance might then entail a retrospective rejection. When he did move into color, with Equinox Flower (58), Ozu thereafter nailed down the camera, which is so conspicuously in motion throughout his Thirties films. According to David Bordwell, “the emblem of all Ozu’s refusals” was the restricted camera height that he began to adopt consistently from the early Thirties, that position about three feet above floor level that again creates an aesthetic and graphic pattern out of conscious elimination. For a while, it also became the emblem of a critical argument that Ozu could be understood only through his sheer Japanese-ness, and that everything in his films was seen from the point of view of someone sitting on a tatami mat.

Equinox Flower

From these technical and titular strategies, it’s a short step to far-reaching formal ones, where suspensions, suppressions, and forestallings create playful gaps in the Ozu image. Consider the opening of Tokyo Story, when Shukishi and Tomi Hirayama are packing for their visit to their two married children in Tokyo, with a stop first to see their younger son, Keizo, in Osaka. The arrangements for meeting Keizo are spelled out, and the film then cuts to some transition shots—a row of tall industrial smokestacks, a railway station—that should be Osaka but are not. That visit, as we learn from a later conversation, has taken place but been elided by the film, and we are already in Tokyo.

Then there is the early conversation in An Autumn Afternoon in which Shuhei Hirayama discusses meeting two friends for an after-work drink. One of them demurs, saying he wants to go to a baseball game. There is a transitional flurry of shots of a baseball stadium lighting up at night, then the film cuts to a bar where the three friends are drinking. The baseball fan, it transpires, passed up the game. So the transition, retrospectively, becomes a bridge to nowhere; it is a tease, a joke, a “what if,” and, of course, an elaboration of narrative space in its own right. When we come to the narratives, and the character dramas, this playfulness—the suspensions, the equivocations—continues to operate, most strikingly in the maneuvers to marry off a daughter in Late Spring, Early Summer, and An Autumn Afternoon, which eventually produce likely prospects whom we are never allowed to see.

This leads to one of the major divides in Ozu criticism, between Donald Richie’s view that the revelation of character is paramount, which is why plot is so unimportant to Ozu, and David Bordwell’s emphasis on the works’ formal processes: “Both the films’ overarching structural rigor and their overtly playful narration work to minimize character psychology.” It’s possible, though, that they’re both right and both wrong, that the processes of ellipsis and suppression wouldn’t have worked as they did if there hadn’t been an answering conception of character, one of doubting and disappearance, of substitution and duplication. The “I, but . . .” formula is a principle not just of doing but of being.

Late Spring

The film doesn’t use formal strategies to minimize her psychology, but one of the most significant examples of character suppression in Ozu is Noriko in Tokyo Story, suspended between the image of a dead husband she cherishes for his parents’ sake and a future she finds untenable (“I don’t know what I will do if I carry on as I am”). Her personality is another bridge to nowhere. This is a dramatic conception of character, but the formulation of emptiness—one of Ozu’s figures of style in his transitional, intermediary, still-life shots—also has an absurdist quality, pushing toward the comic. Is Noriko cousin to those sweet young things of indeterminate function who pop into Hirayama’s office at the beginning of An Autumn Afternoon, their main function being to be quizzed by him about their age and marital prospects, since they exist only as simulacra of his daughter?

Or they may have distantly sprung from the comic. The feckless students who inhabit Ozu’s campus comedies are necessarily simple figures, but they are called on to fulfill cycles of disappointment and failure that only in later films will have to be figured as spiritual loss. I Graduated, But . . . and I Flunked, But . . . are a matching set of mirrored comedies: in the first, the newly graduated hero finds that his diploma is not a passport to a job; in the second, the flunking hero sees his successful fellows go straight into unemployment, so happily re-consigns himself to student life—cheerleading, that is, not studying.

The student friends of Days of Youth (29), Watanabe and Yamamoto, are rivals for the same girl, Chieko. When they both lose her on the ski slopes to another student, they wind up back in their student rooms, with Watanabe optimistically sketching out in mime the “better one” he will find for Yamamoto. Made under the sign of Harold Lloyd—literally, with posters of the latter providing apt student decor—Ozu’s silent comedies are physical comedies of mime, acting out, imposture (the roommates of I Flunked, But . . . use an elaborate silhouette play to order the food they want from a nearby bakery).

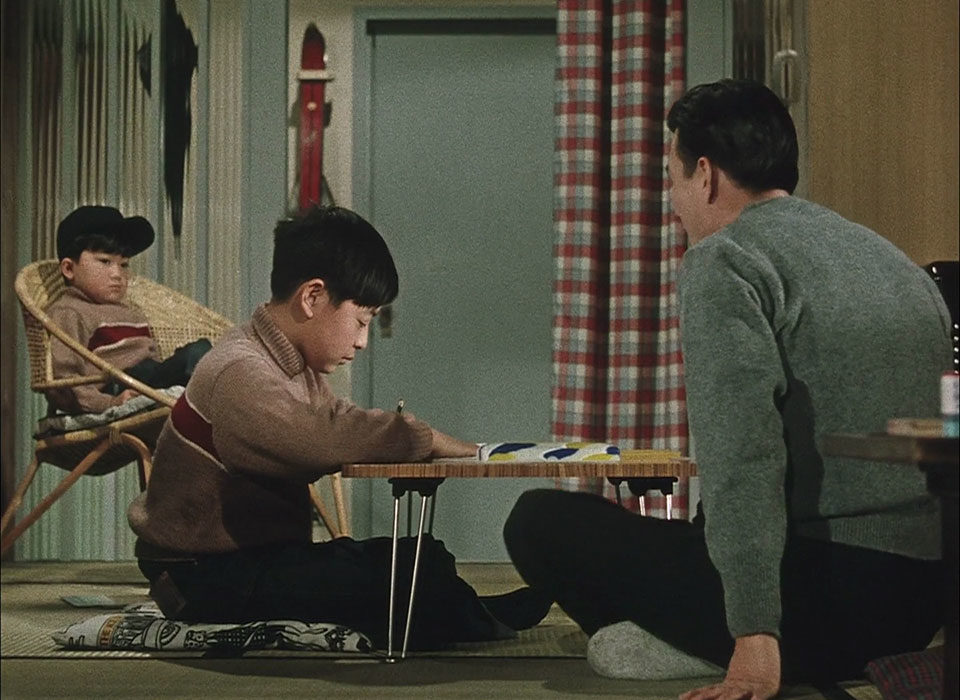

I Was Born, But . . .

Another kind of mime used by Ozu, as described by Bordwell, was sojikei, or “similar figure” compositions, in which two actors would be arranged “so that in posture, placement, or orientation they became compositionally analogous.” This could be extended into a kind of choreography—Ozu’s students are much given to doing odd little synchronized jigs—which possibly helps to subordinate “the individual to the frame’s overall spatial or temporal rhythm.” It possibly also becomes another kind of character comedy—a comedy of character manqué, or its surrender to such routines. Something about it brings to mind that favorite Ozu scene-setting or “intermediary” shot: clothes stretched out on a washing line in mocking imitation of their absent wearers. Father stands among them doing exercises with a chest expander in I Was Born, But . . . ; the last shot of Good Morning (59) honors the drying shorts of the boy who can’t join in his friends’ farting games without losing control of his bowels.

In between the student comedies of bodies in antic motion and the late films of spiritual irresolution, some fascinating Thirties melodramas bring things very much to the point. That Night’s Wife (30) is a thriller in which a penniless commercial artist steals some money to buy medicine for his desperately ill child, then spends the night holed up in his apartment with the detective who has pursued him (the latter for most of the time held at gunpoint by the artist’s wife). Gradually, around such Ozu domestic still-lifes as a teakettle steaming on the hob, an exchange of sympathies takes place between thief and detective, a Conradian secret sharing, no less, in what must be Ozu’s most Western film (the use of identifying motifs such as the detective’s gloves, and Ozu’s initial idea of confining all the action within the flat, even suggest something Hitchcockian). Eventually, the artist decides to pay for his crime, and he and the detective go off into the dawn, almost arm in arm.

An Inn in Tokyo (35) was one of Ozu’s series of four films featuring the drifter Kihachi (Takeshi Sakamoto), usually wandering through a desolate landscape in search of work and sustenance for himself and his son (or here, two sons). In An Inn, he meets a woman as adrift as himself, and another ailing child prompts another hero to theft. Character correspondences are brought out in some “ghostly” substitutions and dialogue echoes: “You’ve got the wrong person,” says a prostitute when Kihachi tries to give her a necklace he has bought for the woman he believes has now abandoned him. “You’re asking the wrong person,” says the landlady of the inn when Kihachi goes to her for money. It’s an effect Ozu would carry over to Tokyo Story: “Being in Tokyo is like a dream,” says the mother on her arrival. “It’s just like a dream,” says her bewildered daughter Shige after her mother’s sudden collapse and death.

Good Morning

The theme is picked up in Good Morning by the elderly Tomizawa (Eijirô Tono), retired and almost perpetually drunk, who declares, “Life is an empty dream.” This may be the sentiment, unspoken, behind Shige’s declaration, and perhaps it circulates through all the interchanges and transactions, particularly the arranged marriages, in Ozu’s films. In which case, Good Morning is its most thoroughgoing correction. This may not displace Tokyo Story as Ozu’s generally acknowledged masterpiece, but it is one of his most extraordinary films, a pellucid examination of the ties that bind in a suburban community, a strangely yet charmingly defined artificial world over which the comic spirit of not Harold Lloyd but Jacques Tati seems to hover.

Good Morning is usually classified as a remake of I Was Born, But . . . , though it is in fact more of a satellite, taking off in a different direction from the conceit of children going on strike against the perceived injustice and inanity of the adult world. Here the two sons of Keitaro Hayashi (Ryu), told off for making too much noise over the television they want, declare that grown-ups make too much unnecessary noise with their good-mornings and how-are-yous, and go on a silence strike.

This sparks a chain reaction of neighborhood paranoia, until communication is restored (“Those unnecessary words are the lubricating oil in our society,” the lesson is spelled out), along with some plain transactions and not-so-secret sharing (Tomizawa becomes a salesman and Keitaro buys a television from him for his boys). The boys’ aunt (Yoshiko Kuga) meanwhile carries on a kind of romance—no arranged marriages here—with their unemployed English teacher (she brings him translation work, naturally enough). But they find that “important things” are hard to say, and carry on their relationship by discussing that most necessary of unnecessary Ozu topics, the weather.

Richard Combs is a regular contributor to Film Comment.