By Imogen Sara Smith in the January-February 2017 Issue

Finest Hour: Army of One

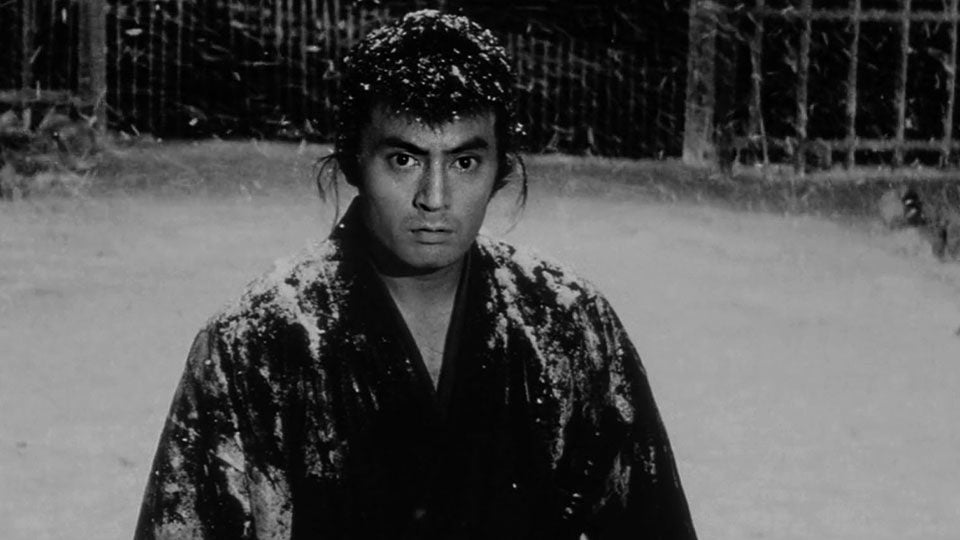

Tatsuya Nakadai embraces the fury and mystique of the samurai in The Sword of Doom

What a terrifying film!” was Tatsuya Nakadai’s first comment after a screening of The Sword of Doom (1966) at the Museum of the Moving Image last November. Having just watched himself, 50 years younger, slash his way through scores of opponents in the bloody, phantasmagoric climax to Kihachi Okamoto’s samurai classic, Nakadai seemed as stunned by the film’s ferocity as anyone in the audience. If it was hard to connect the gracious and engaging 83-year-old actor with the icy, disturbingly beautiful killer on screen, it can be no less bewildering to compare his performances from film to film. Few actors have displayed such protean ability not only to embody the furthest moral extremes but to transform themselves, outwardly and inwardly, for each role—without ever “disappearing” into a part. He is too singular for that.

From the January-February 2017 Issue

Also in this issue

Born in Tokyo in 1932, Nakadai began his film career not long after the end of the American occupation in 1952. Trained in modern theater and steeped in Hollywood movies, he was Japan’s answer to postwar “new men” like Montgomery Clift, James Dean, and his hero Marlon Brando, with their raw emotions and troubled, ambivalent masculinity. His star-making role was Kaji, the sensitive rebel with a cause in The Human Condition (1959-1961), Masaki Kobayashi’s grueling epic of Japan’s wartime atrocities and suffering. In a demonstration of his range, during the making of this trilogy he took time off to play Unosuke, the rakish, serpentine villain in Kurosawa’s samurai Western Yojimbo (1961). The director cast Nakadai opposite his great star Toshiro Mifune, seeing in them the contrast between silk and cotton, between a snake and a lion: the younger actor supple and enigmatic where the older was gruff and direct. The same qualities define their pairing in The Sword of Doom. It was Kurosawa who first drilled Nakadai in how to stride like a samurai, for his blink-and-you-miss-it walk-on in Seven Samurai (1954), and it was Mifune whose prowess at sword-fighting he practiced tirelessly to match.

In Hollywood, such a handsome actor might have struggled more against matinee-idol typecasting, but Nakadai’s plasticity and mercurial flair meant he was never defined by his huge, lustrous eyes, sculpted cheekbones, and cupid’s-bow lips. His features seem to be recast for each role, with Kaji’s soulful, liquid gaze hardening into the vitreous sheen in Unosuke’s eyes. In The Sword of Doom his sleek face looks cold and dead, eyelids half-lowered, muscles lax except when a cruel twitch pulls his mouth sideways. Two years later in another Okamoto film, the raucous but gentle-hearted action-comedy Kill! (1968), he is lovably scruffy, all quizzical grins and hangdog charm. Perhaps his smooth, resonant bass voice is the most unchanging element of his presence. His acting can be stylized, dance-like in its bold physical expressiveness, or coolly restrained, but it always seemed to be fed by some inner wellspring. He has said that while people talked about the expressiveness of his eyes, he actually had no idea what he was doing with them; he assumed they were simply windows to what he was feeling.

In an ominously quiet scene just before chaos explodes at the end of The Sword of Doom, Nakadai closes his eyes and, in a reverie, describes the winds blowing through the mountains, harking back to the opening scene of the film, set in the Great Bodhisattva Pass (Daibosatsu toge, the movie’s original title). Then he opens his eyes, lifting the lids as slowly and majestically as a theater curtain, and gazes upward—a breathtaking image. By this point his character, Ryunosuke, has slaughtered a host of people, including his common-law wife and an innocent Buddhist pilgrim; he is a vicious, arrogant, heartless psychopath with a gift for exploiting the weakness of others. Yet he is profoundly mysterious, evoking awe and spine-chilling fascination, like a snake that hypnotizes its prey.

The film is only somewhat less baffling if you know that its source was a 41-volume serialized novel from the early 20th century that illustrated Buddhist ideas of karma. Nakadai has explained in interviews that Ryunosuke’s sins are inherited through the laws of reincarnation, but the brilliance of his performance and the film is that neither ever nails the character down. Does his motiveless violence spring from karma, insanity, or consuming devotion to the art of the sword? He might be a tormented puppet, an exemplar of samurai arrogance, or even an angel of death—when he first materializes and fells the pilgrim with a single stroke, the old man is praying to be released from life.

The keynote of Nakadai’s performance is a strange passivity; in many scenes he slumps on the floor, limp and sullen, drinking sake and staring at nothing. He is at once terrifying and terribly sad, lurching from inertia to frenzied violence, embodying form without content, action without purpose, pride without character. He is, above all, defined by his style of sword-fighting, first demonstrated in a formal fencing match. The adversaries face off with raised swords, but then, in the tense stillness, Ryunosuke lets his droop. His knees bend, his head wilts, life seems to drain out of his body. He slowly retreats, feet slithering across the floor, until he is backed up against the wall; then, as his opponent finally rushes in with a blow, he strikes from nowhere, a single movement too quick to see—and wins. In an essay accompanying the Criterion Collection DVD release, Geoffrey O’Brien identifies this style as mumyo otonashi no kamae (form without sound or light). Other characters, in particular the staunch fencing instructor Shimada, played by Mifune, condemn the style and see it as the root of Ryunosuke’s evil. “The sword is the soul,” Shimada says. “Study the soul to know the sword.” But the film poses the question of whether Ryunosuke’s “silent form” of fencing is the expression of his nihilism or the cause of it—a tempting metaphor for Nakadai’s acting: does it happen from the outside in or from the inside out?

Shortly after the first fencing match, Ryunosuke is ambushed as he pads softly through a pine forest. Lofty, mist-hung trees form a cathedral nave along the path, and he walks with unhurried grace through the crowd, felling each man with a single clean, calligraphic stroke of the sword. The camera watches this too-lovely bloodbath from behind, then closes in and circles around to show Ryunosuke’s face. His eyes are glassy, his lips parted in a sick little smile; nothing in the movie is scarier than this air of drugged pleasure he derives from killing. The fight in the wood is mirrored by a later scene in which Shimada, ambushed on a snowy night, similarly dispatches a horde of attackers. Ryunosuke stands back and watches through the falling snow, his expression a stricken mixture of fear and fascination: he has finally found his match.

As he unravels after this shock, Ryunosuke is wracked by seizure-like nightmares. Finally, in a magnificent waking dream, the shadows of people he has killed advance on him, and he slashes through layer upon layer of bamboo drapes, trying to destroy his own memories, his enemies, himself, the whole world. After four days shooting the final massacre, Nakadai recalled, he felt “I myself had lost my mind as well.” He gives himself to the role the way fuel becomes flame, the way snow becomes air. He is sublime.

Imogen Sara Smith is the author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City and Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy, and has written for The Criterion Collection and elsewhere.