By Nick Pinkerton in the September-October 2015 Issue

Blast from the Past

George Eastman House’s new annual celebration keeps a venerable but vibrant medium alive

In 1948, Eastman Kodak introduced a new motion-picture stock that used transparent plastic film made of cellulose triacetate to back the gelatin emulsion. This new base was a replacement for nitrocellulose, the standard material used for film since the dawn of moving pictures. The discovery of an alternative to nitrocellulose that met industry standards for durability and cost-effectiveness was an innovation greatly to be desired, for nitrocellulose—“nitrate,” for short—was notoriously flammable, burning at a combustion rate 15 to 20 times that of wood. In layman’s terms, it blew up real good.

From the September-October 2015 Issue

Also in this issue

This trait resulted in numerous fatal projection booth fires of the sort dramatized in Giuseppe Tornatore’s 1988 weepie Cinema Paradiso. One notorious example: in 1927, at Montreal’s Laurier Palace Theatre, a nitrate fire, the nitrogen oxide gases it produced, and the panicked stampede that followed resulted in the death of 78 children, as well as, shortly afterward, a law forbidding anyone under the age of 16 access to cinema screenings, which remained on the books until 1961. (The movie playing that day was the unfortunately titled Stan Laurel comedy Get ’Em Young.) Nitrocellulose, aka guncotton, was also an ingredient in the military firearm propellant cordite, and the scarcity of surviving material from the adolescence of American filmmaking might in part be explained by the fact that much early cinema was put to the task of shelling the Kaiser’s trenches.

The new cellulose triacetate, known as “safety” film for self-explanatory reasons, quickly replaced nitrate, whose manufacture ceased altogether in 1951. Once the changeover was complete, there’s nothing to suggest that there was a public outcry comparable to the faint din that’s been raised by diehard cinephiles as DCP, having blitzkrieged the first-run houses, has begun to edge out 35mm in independent and repertory venues.

Les Maudits

In a sense, then, those attending the first Nitrate Picture Show, a 10-feature, all-nitrate event held in early May in the George Eastman House’s Dryden Theater in Rochester, New York, were all taking a bit of a gamble—and not just because the program’s bill of fare was not announced until the last moment, or the risk, however slight, of death by fire. (It’s been a long time since the last nitrate casualty, though in 2009 a nitrocellulose print of the 1944 Gene Kelly/Rita Hayworth vehicle Cover Girl ignited after jamming in the projector at the Stanford Theater in Northern California.) The question in my mind before the curtain rose on the first screening, and undoubtedly on the minds of others seeing their first nitrate projection: is there really any visual difference between nitrate and safety film?

While we can point to certain things that set nitrate apart—its high silver content, its flammability—there is no quantifiable evidence that states how these differences are reflected in what an audience sees when nitrate is projected. In part this is because nitrate prints are seldom seen projected, period. The number of venues in the U.S. equipped to show nitrate is now down to three, and the Dryden is now the only nitrocellulose-ready theater east of the Appalachians, the Museum of Modern Art having eliminated nitrate projection after their 2002-04 renovation. Additionally, there are only so many extant nitrate prints around that can still run through a projector—up through the Eighties, some archives were still destroying their nitrocellulose holdings once the films had been transferred to safety copies.

The George Eastman House’s Senior Curator of Motion Pictures, Paolo Cherchi Usai, is not one to let prints gather dust, however, and before the first screening of the fest, Casablanca (42), he delivered a clear mission statement: “Film preservation finds its fulfillment in the projection booth.” That the Nitrate Picture Show has appeared now rather than, say, 10 years ago, is not a coincidence; it’s part of an identifiable movement in programming to draw attention to format, hastened by the emergence of low-risk, low-overhead DCP. (See the conversion of Los Angeles’s New Beverly to an all-35 house, or the “This Is Celluloid” series at Anthology Film Archives.) As Usai put it to me later in a phone interview: “Cinema had to die in order to be taken seriously.”

Casablanca

There is a nitrate difference, and I didn’t hear a single person present at George Eastman say otherwise. During Casablanca it was evident in the sybaritic twinkle in Sydney Greenstreet’s eye, and the fretwork detail visible in a piece of fabric which Ingrid Bergman briefly fingers in an open-air souk. Nitrate’s fine-grain image especially seems to reveal the warp and weft of costumery, the gold thread in Hedy Lamarr’s gowns in Cecil B. DeMille’s Technicolor Samson and Delilah (49), a caravan of Orientalist bric-a-brac and polychrome diaphanous silks. For some, the difference is most visible in silver-rich black-and-white nitrate, as in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (34) and René Clément’s largely forgotten submarine thriller Les Maudits (47).

“There isn’t one single nitrate quality. It depends from film to film,” Jurij Meden, the newly arrived curator of film exhibitions at George Eastman, told me via phone, before adding: “Nitrate really, really shines in black and white, because in nitrate the concentration of silver was very high.” Projectionist Benjamin Tucker also cited the “richer” blacks and “whiter than ever” whites, virtues to which he added the “romantic” aspect of watching “David O. Selznick’s personal print, [in which] the flaws that I’m seeing are part of the history of the viewing of that particular print.” Usai is in no doubt that nitrate has a unique quality, though it is not so easy to articulate. “Our language [is] so inadequate to rationalize this difference,” he explained, precisely because the study of cinema as a visual art has a long ways to go before catching up with art history’s specialized vocabulary.

The Casablanca print was, incidentally, the last nitrate print to screen at MoMA—the same print. Every film shown in Rochester was, in effect, a relic, the oldest being William Wellman’s 1937 screwball Nothing Sacred—a venerable 78 years young. Nitrate ages at variable rates, depending on storage conditions, but like all film it doesn’t improve with time. The resulting shrinkage and warping of prints means that projectionists often have to be extra-vigilant about riding the focus through screenings. (The curved gate of the 68-year-old Century Model C projectors in the Dryden booth gives more leeway to account for shrinkage, while the Century’s enclosed system, which can contain potential conflagration, is standard for nitrate projection.) Tucker, one of the three men in the booth for every screening, walked me through the precautions, including fire shutters that would seal off the booth portholes from the auditorium, and “fire rollers” that would isolate fire in one part of the projector. “People think that it takes guts to project nitrate,” Tucker said. “I like to remind them that they got here in a steel box loaded with gasoline, and their house has a gas tank in the basement. People used to smoke cigarettes and pump gas at the same time. You just need to be careful.”

Nothing Sacred

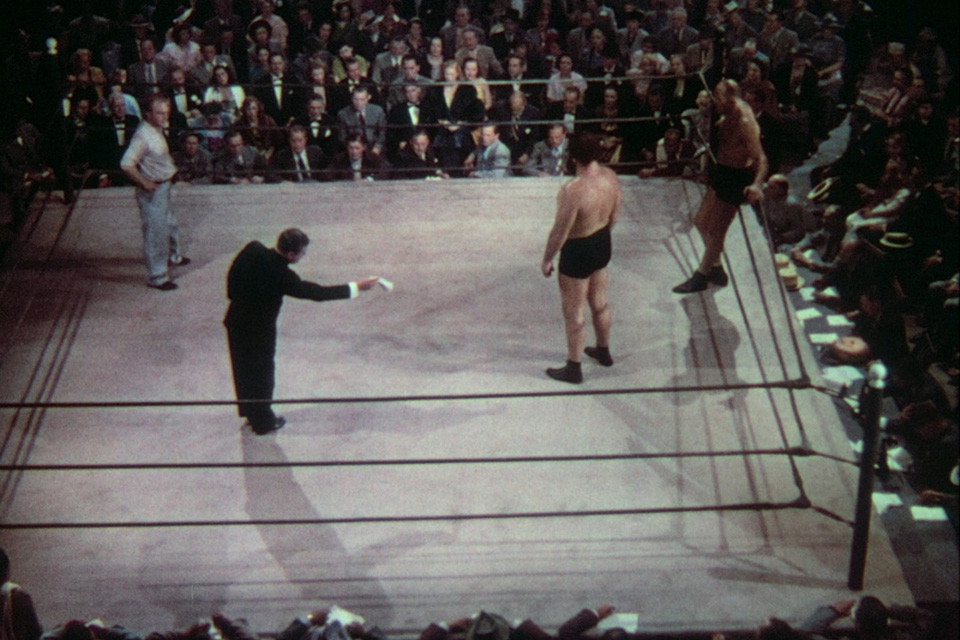

But what makes it worthwhile? Still stuck for a decisive definition of the nitrate difference, I turned to the pertinent section (written in 1999) in The National Parks Service Museum Handbook, a reference guide to handling museum collections: among the qualities of nitrate film it enumerates are a “good range of clear details, even in the dark shadow and bright highlight areas,” and “excellent depth of field.” To the last-named aspect I would add that the dimensional nitrate image seems to have a more pronounced sense of layered planes of space, seen in the web of smoke through which Fredric March and Carole Lombard watch a wrestling match in Nothing Sacred, or the almost tactile cool wetness of the deadly lake in John M. Stahl’s Leave Her to Heaven (45). The received wisdom on the 3-D craze of the early Fifties has it that stereoscopic cinema, the technology for which had existed for a number of years, was thrust toward audiences to offer new sensorial inducements that television couldn’t match. Seeing these nitrate prints, however, I thought of another, perhaps subconscious motive for the adoption of 3-D: it was an attempt to restore the depth that cinema had lost in the conversion to safety film.

Several extenuating circumstances make defining the nitrate look even more difficult: The effect of bas-relief depth I’ve describing has also been ascribed to Technicolor, and the vaunted beauty of nitrate may not be attributable to properties intrinsic to nitrocellulose but to the fact that the surviving prints were struck from original negatives, and are therefore instances of the meticulous lab work that was once an industry standard. Yesterday’s standard is tomorrow’s rarity, however, and Usai ruefully framed a pessimistic scenario: “Two hundred years from now this strange little festival happening in Rochester, New York, may become the safety picture show in some other venue…” The Nitrate Picture Show, then, is one small way to keep the celluloid torch burning.