By Melinda Ward in the November-December 1973 Issue

Interview: An American Family

The filmmakers discuss their groundbreaking documentary series in this 1973 conversation

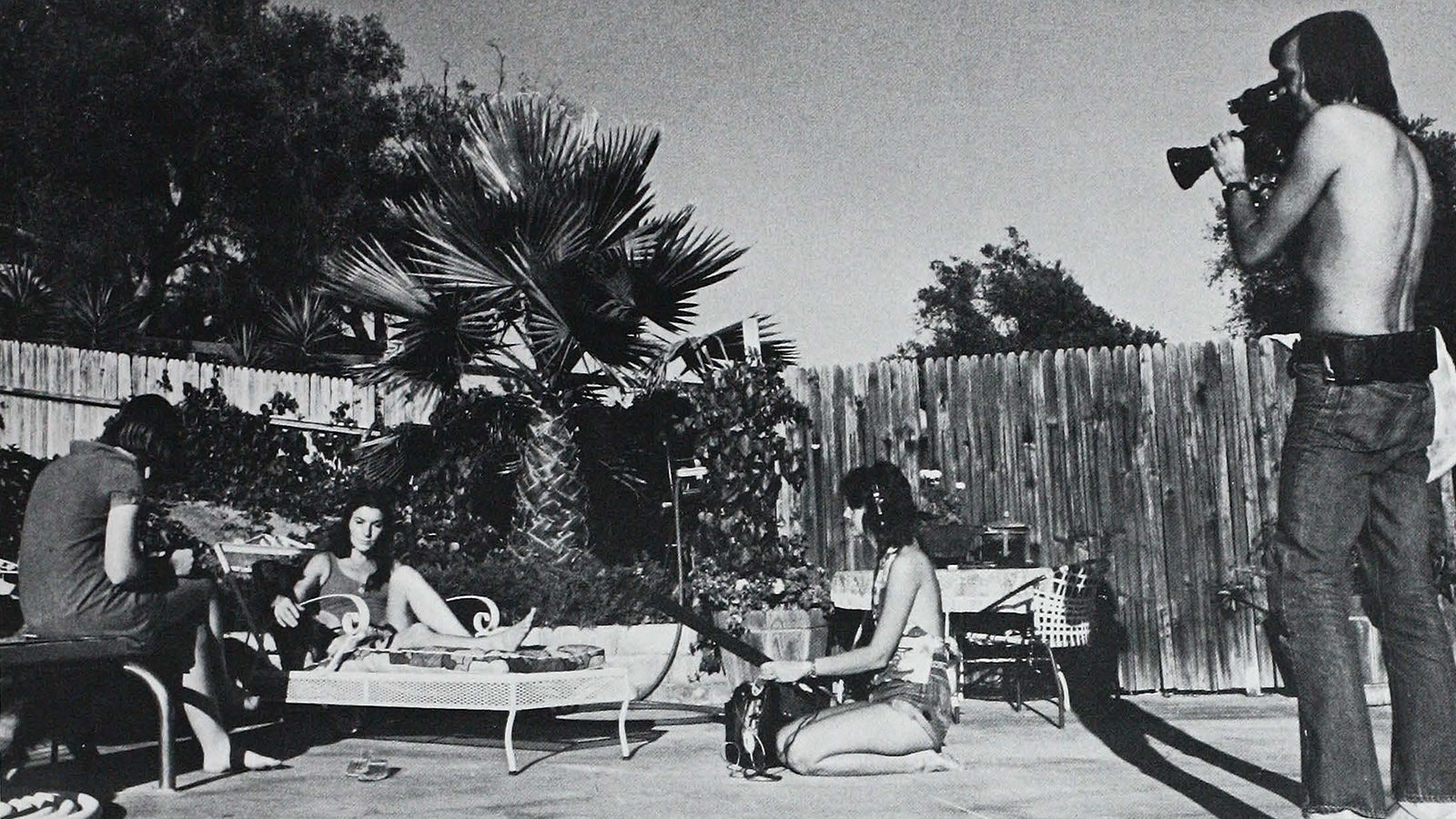

An extraordinary amount of physical and psychic energy went into the making of An American Family, and major credit must be given to Susan and Alan Raymond, who spent the better part of every day for seven months living with and recording the Loud family. This meant giving up their personal freedom in daily matters and dancing only to the tunes called by the Louds. The responsibility for decisions regarding what to film and what not to film, as well as the responsibility for maintaining a working relationship with the Louds, was theirs. Most of the three hundred hours of footage shot for An American Family—and the twelve hours that form the final film—was shot by the Raymonds.

From the November-December 1973 Issue

Also in this issue

John Terry and sound man Al Mecklenberg spent five weeks filming Lance, probably the most complex personality in the Loud family, in Denmark and Paris. Terry produced and photographed thirty-five hours of Super 8mm film, from which several sequences appear scattered throughout the final series.

Although the Raymonds and John Terry all worked on An American Family, they had actually never met before the afternoon of this interview, May 12, 1973. Consequently, what follows is less a formal interview than a swapping of ideas and information on the Louds, the editing and production of the series, the filming techniques used in An American Family, and the problems and rewards of cinema verite filmmaking. As might be imagined, the conversation went on for hours, of which approximately one third of the total is represented here. A few minor corrections were made by the Raymonds and John Terry in the final edited manuscript.

The Raymonds have been working as a team in documentary films for the past six years. Before that, Alan worked as an editor for Drew Associates and Susan was studying sociology and anthropology. Since they began working together (usually Alan does the photography and Susan takes sound, but they have both also done some producing and directing), they have worked with or for many of the major producers of American documentary films (WNET, the Maysles Brothers, and Bill Jersey). Alan Raymond was also the director of photography on Jim McBride’s feature, Glen and Randa. The Raymonds have their own film company in New York and, at this writing, are working on several projects including their own feature-length cinema verite documentary.

John Terry is an independent filmmaker with a background in architecture and still photography. He teaches filmmaking at MIT and has, in the last year, completed two films: The Doctor, which he calls a men’s film, and an hour-long documentary on street life in Paris.

Could all of you give an example of a typical week? How much time did you spend with the Louds? How much of that time was spent filming? How much time did you spend with the rest of the production staff?

JOHN TERRY: I’ll start with the typical day. There was no problem getting up before Lance. We didn’t stay either in the same hotels or houses that he stayed in, either in Denmark or Paris.

ALAN RAYMOND: Would you have lived with him if you could have? Because we never really wanted to live with the: family, even though Pat often offered us a bedroom.

JOHN: We would have thought about it at the beginning but I think it was good that we didn’t. Good for us primarily. We just needed to have that space away from him. Al Mecklenberg and I would arrive at the farm at about nine or ten in the morning. Most of the scenes there repeated themselves daily. Getting up and breakfast. We filmed the routine a lot until I was sure it was that and nothing more. In some sense, the routine was important to film because it was so uninteresting. It reached a point where the routine itself got them down and they wanted very much to leave Denmark. We wanted to establish that.

Lance lacks a certain amount of imagination about doing things. He had some trouble figuring out what to do in Denmark. A lot of that was due to lack of money. Many of his ideas are just conceived of in terms of having money to spend.

ALAN: Did anybody think anything about your filming it, or did they just all go along with it?

JOHN: They went along with it very easily. Lance quite easily adapted us into the role he had with whoever he met. He would say. “We’re making a movie for educational television in America.”

Let’s use the scene in the Paris cafe as an example. Would people just come up to Lance and be told by him that you were making a movie and then you’d start to shoot whenever you felt like it?

JOHN: That’s not a typical scene at all. The guy who came up to Lance in that scene was the only person we met the entire summer who did not want to be filmed—he really did not want to be filmed. I persisted because we’d been waiting so long at that cafe for something to happen. I wasn’t going to give it up because he didn’t want to be filmed. He actually got very nasty about it. He put his hand over the lens a few times. Lance isn’t about to give him a straight story either. I mean, Lance adapted the story to fit the situation very well. He said he was writing a play about women’s liberation.

ALAN: You would be rolling a lot of the time?

JOHN: Yes. But then there would be whole days when we didn’t shoot a thing, because nothing happened that we hadn’t already seen.

ALAN: Do you feel a lot of good stuff was left out in the final series?

JOHN: Yes. I was always trying to concentrate on Lance’s relationship to his family, but it seemed like the next most important thing was Lance’s development as a person. And he did change during the time of the filming. He’d basically never been that far away from home and the world he knew. And he’d never been out of the country before. The biggest disappointment to me was that the shows, as they came on, didn’t really have much to say about changes in Lance. The series didn’t look very deeply at him. He is much more interesting than you ever get an idea of in the show.

Susan and Alan Raymond shooting An American Family (1973)

ALAN : We didn’t live with the family. We also chose not to live with any of the other production people who were in Santa Barbara and connected with NET. We actually sublet John Ireland’s house. We were about ten minutes away by car from the Loud house. Our routine simply was that we would get up… well, it would vary. We didn’t make an attempt to get there early in the morning. We only filmed one breakfast scene. One of the reasons that we filmed only one was because it was one of the few times Bill was around. There was a theory that it would be nice to get them altogether. But Michele, Pat, Susan and Alan Raymond. that required getting up at five o’clock in the morning.

JOHN: But I think the fact that you did film the one where he was home doesn’t bring out the fact that he wasn’t there most of the mornings.

ALAN: True enough. I would say we fell down as far as filming breakfast. If breakfast is considered to be a crucial moment in the Loud family’s life, we were pathetic, because we just couldn’t get up.

JOHN: I lapsed on the other end. Lance stays up until three or four.

ALAN : It was one thing to get up at five in the morning and get to the house by six. They all got up about six o’clock. But it was another thing to have to realize that we were going to stay there until they went to bed, which we did every night. Most of the time, we would get to the house by late morning. Sometimes there would be just Pat in the house and sometimes, it would be the kids. We just tried to determine, without any kind of formal questioning of them, what each of the family members was doing on a particular day.

SUSAN RAYMOND: Sometimes, we didn’t have to question because we had been there all the time and we had heard the conversations about planning. We knew, just as well as they knew, what they were going to do.

There seems to be two kinds of events: the event and the nonevent. The event being the routine that is predictable. You don’t know what is going to happen during the course of that event, but you know the event itself will take place. School registration, or Pat’s visit to her mother’s, could be anticipated in advance. Whereas the non-events are things that just happen, such as Pat’s skirmish with Michele.

SUSAN: You mean the one with the dog and the bicycle? That was fascinating and an exciting moment for us. There was nothing happening at that house. Well, that day we decided nothing’s happening but we’re not going to sit around because we’re bored—we’re going to film because we’re bored. So we filmed them and that all happened. That was great.

ALAN : We didn’t really make much of an attempt to film routine.

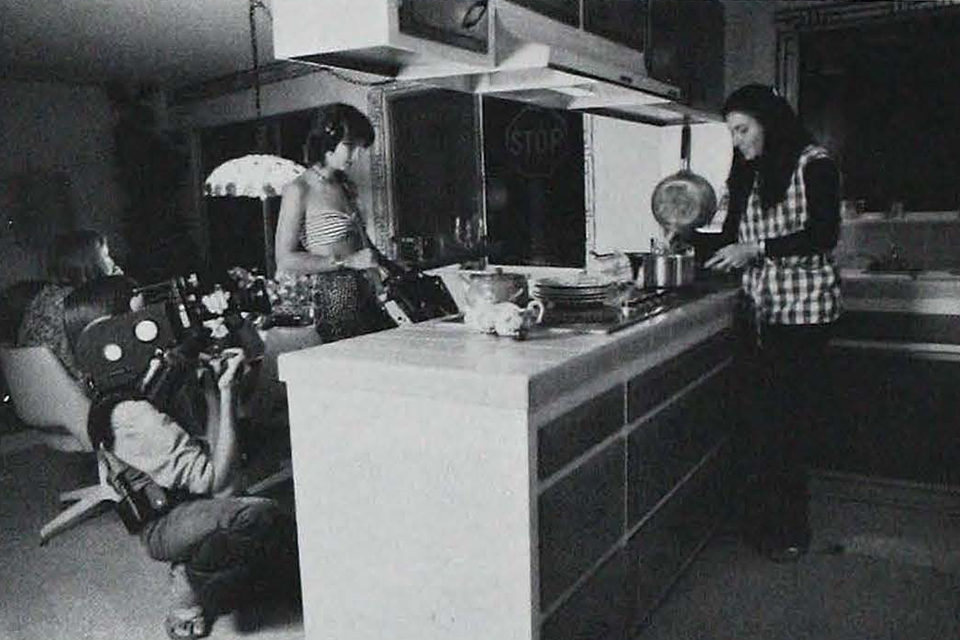

SUSAN: We would be sitting around and, all of a sudden, something would be going on in the boys’ room, or Pat would be in the kitchen and Delilah would walk in and a conversation would start. It’s instinct after a while. There’s no other way to explain it. You just feel, “We should get up and do it. “We would always have the equipment around, so we’d just get up and start filming. That’s the way we lived our lives.

ALAN: I would say that we could start filming literally within a minute or two.

SUSAN: The house was lit and wired for sound.

ALAN: We would tend to shoot complete rolls, which is eleven minutes per roll. We would not begin to do something and then shut the camera off even if it seemed that nothing was really happening. When we did decide to film, chances are we would expose a lot of film. So that if we started in the boys’ room shooting a scene with them, we would keep the camera rolling and then move to another part of the house and try to see whether or not we could begin to devise some sort of order to the events that were happening.

JOHN: It’s nice to have that kind of freedom where you don’t have to worry about how much film you’re using.

Was that shot where Lance says goodbye to his mother at the cab in front of the Chelsea and is then seen going all the way up the stairs back to his room yours, Alan?

ALAN: Yes. That was almost a full camera load. There were several shots in Show Two that ran very long. I love that walk through Central Park. That’s a walk from the west side of the park around 72nd Street all the way to the Bethesda Fountain. It must run close to ten minutes. It’s an interesting scene because they’re trying to communicate. It’s one of those classic non-communication scenes, of which there are many, but it’s nice because you are able to see how the conversations don’t connect. He goes off on a tangent and she goes off. Those long takes were really nice. We always tried for them. That’s the way cinema verite works out best. I always feel that, when there are a lot of cuts internally within a scene, people who are watching always begin to suspect that the scene has been created.

JOHN: It’s very important that real time events like that get on television. Most people have never seen reality as it happens in real time sequence on television. Audiences are becoming more and more aware of that. There was a time when you could put anything together in the editing.

ALAN: Ultimately, it all comes down to relationships. One of the problems with cinema verite films in the past—and still now—is that they try to build them around events. In the Drew Associates days, the films would be structured almost like a contest. Someone would enter into an arena and win or lose, and somehow that would spur on some sort of interest in the film. But what’s really important is how people relate to one another. That’s what good dramatic films are about, that’s what all good fiction is about. In this instance, at the risk of boredom at times, you are able to see what the real pace of a conversation is, how people don’t always respond immediately, and how the pauses occur.

JOHN: That’s the real value of the series, but I don’t think it’s realistic to say that there weren’t choices made at all times in the shooting and the editing. There’s less of that in using the moving camera and the long take, but the question still exists.

ALAN : You have to assume that the people behind those machines are in some way interpreting it. I’m not trying to make a case for being like a video tape camera in a bank, recording hour after hour.

An American Family (1973)

Would you say that your camera and sound positions were often determined by practical factors such as the amount of space you had in a room? For instance, at Pat’s mother’s birthday party, you didn’t seem to have many choices of where you could be. Would you say that because of practical necessities, most editorializing, if any, came about by accident?

ALAN: No, I always felt that I tried to depict on film what was happening there whether it meant filming detail, or background, or trying to show spatial relationships like in the strip mining footage. There is a definite “art” to the photography. But, in some way or another, it still has to record what is happening beyond how you choose to frame a shot, or zoom in and zoom out. You still have to assume that you are, to the best of your ability, rendering the event, that you are seeing personally, in such a way that when people see it abstracted on film, they feel they’re not getting a false version of what’s happening.

JOHN: That’s my main concern at all times. How to make events, as you understand them, visible. It’s not as if every camera position is equally revealing.

SUSAN: I would, at all times, be concerned with good sound—and wherever that position was, I was going to be there, taking into account both camera movement and the Louds themselves.

JOHN: I like to use various techniques. I’ve never found the same situation twice. In the sequence where Pat and her mother go around the old house, I felt you were taking the five-feet-back attitude, pretending you weren’t there. I thought that was unproductive. They were so self-conscious of themselves and of the camera. My approach would have been to encourage them to acknowledge the camera’s presence. I would perhaps say something like, “Take the camera on a house tour,” instead of letting them give the kind of house tour that they did. People often try very hard to give you what they think you want. I felt they wanted to please you so they went around and self-consciously said, “Isn’t that where Lance did so-and-so?” as if they’re reliving it all for themselves when actually they’re doing it for you.

SUSAN: I don’t feel that at all. There were two emotions that were going on. When Pat is with her mother, she’s very uptight, she’s very uncomfortable, she doesn’t know what to say. As you see from the visit, they had very little to say to each other of any meaning, right? Secondly, she was visiting a home that she remembered many happy times in. She was very distracted because of these emotions.

JOHN: You might have dispelled some of that. I can’t really criticize because I wasn’t there. But sometimes, you dispell that uptightness by encouraging them to tell you as they would, as if they were telling you what’s important about this. What I like to do, too, is when the kind of situation presents itself where you are alone with a person, just give them the chance to talk to you, to the camera, and just see what happens. Everyone can’t do it. Everyone doesn’t want to do it. If nothing happens, you don’t have to use it. But if you get something…

SUSAN: Like that scene you shot on the New York rooftop where Lance is saying that he wants to be Peter Pan. Well, I like that scene but I felt it was very jarring in its style. It was very different from the rest of the footage because, as you said, he was talking to the camera.

JOHN: I’m not so concerned with how the style changes as I am with whether or not the stuff talks to me and tells me things I don’t know. And I’m not talking about interviewing. I’m just saying that there are different methods and I like to try lots of different things and see what works. Most of the time, the last thing I want to do is to get involved in the scene.

ALAN: There is one scene that we did that is somewhat similar to what John’s talking about, which is Lance coming into his father’s office after he comes home. That was a real scene. He walked in, his father wasn’t there, and there was a kind of disappointment. He has the secretary get his father on the phone and then he goes into the office. Now at that point, you might think that what we did was say, “Well Lance, what now?” which may have motivated him to pick up the letter. We didn’t do that. He actually made that choice to walk over there, pick up the letter that he had written his father and read it to us. The fact that he wanted to read that letter was very revealing. We didn’t know about the letter, so we could not have guessed what the content was. To me, it works better in the flow of the material than the scene of him sitting on the rooftop, which was a more formalized version of the same technique.

JOHN: I don’t know why one works better than the other. They’re both just scenes that Lance does. Lance doesn’t do many things he doesn’t want to do. I always try to establish a relationship where people can tell me no if they don’t want to do something.

There are times when there is such a strain in their not acknowledging the camera that it becomes a deception in itself. The audience knows, especially after all the publicity, how long the crew was there, how many hours were shot, etc. So that to never admit to the presence of the camera is like trying to force a proscenium-stage-type separation between “actor” and audience. When Pat turns to the camera after an argument with Michele and says to you, “Well, I lost that one,” it’s such a relief. Of course, had you really gotten involved on camera with them over the seven-month period, the film would have been about the relationship between your family and theirs.

SUSAN: That brings up another interesting point: the relationship between us and them over the seven month period. When we did what became Show Two (Pat and Lance in New York), that was the first week’s shooting. No one knew what was going to happen. We didn’t know anything about them and they didn’t know anything about us. Then we went to Santa Barbara and did the breakfas” t scene, the dance recital, the trip to Eugene, and the beginnings of summer planning and vacationing. The summer went along and everyone in the family was very preoccupied with the events in their own lives. Then around the fourth month, things started becoming more regular in the house. The children went back to school, Bill went to work, Pat was back in the house. And the divorce thing happened. It did not have that huge an effect on the family.

Then they figured out, “Well, they are here all the time, every day for sixteen hours and they’re not going to go away and they’ll be here until New Year’s.” At that point, they got into a different relationship with the camera and us. They were more receptive to it and understood it better. They knew what it could do and they started to use the camera. Like when Grant comes home with the totalled car. He knows he’s got the camera there. Lance, particularly, used it all the time. Towards the end, they loved being filmed so much (it had become such a way of life) that they would ask us to be at certain places to film certain things that were going to happen which they felt would be interesting. So they did a complete turn-around. Finally, when we left, they were drastically depressed. They were very, very sad that the camera would no longer be there. They went through many changes. As you watch the series, you can tell that in Show Twelve, their reactions are so different from Shows Two and Three. That’s the period when they’re changing, figuring out what’s happening.

We never got to see a lot of that last period because there wasn’t enough money to do Shows Thirteen through Sixteen, right?

ALAN: That’s right. You don’t see much of it. One of the things that you don’t see is Lance being thrown out of the house, which is the major episode of that period of time. David Maysles once gave us a pep talk when we were going to shoot something for him. He had a theory, which I agree with, that you get your best material at the beginning. I believe that. There’s an initial terrific period. For us, it was probably that first month, out of which they made three or four shows.

JOHN: When you meet someone, that’s when they tell you the most. They’re introducing themselves. They’re giving you essential background information. If you’re not prepared to shoot at the beginning of the thing, you miss a lot.

ALAN : Lance and Pat maintain that they didn’t reveal that much of themselves in Show Two; that they were somewhat intimidated by the camera being there, that they couldn’t really talk as freely as if we hadn’t been there. I don’t know. I think that, unconsciously, they revealed an enormous amount about their relationship in that.

JOHN: Lance is very aware of how long it takes you to get the camera and start shooting and taking sound. I could sense differences in what he would say, depending on whether I had the camera to my eye and was looking through it and was ready to shoot at any moment or whether the camera was across the room and I would have to get it. That’s enough time to change the train of thought, or what you’re saying, everything. Our relationship did go through changes though, where he did that less.

SUSAN: I may be very wrong, but I do believe that they were candid most of the time. The way we lived life with them was with the house lit and ready to be filmed, any room including bathrooms and bedrooms. We’d walk around the house, moving with the camera. We’d come upon a scene and start shooting and they would continue. They were willing to let us film any part of their lives.

ALAN: There’s also the question of how much, not only the Loud family, but anybody, really does confront the members of his family about the reality of their relationships. You always have one level on which you talk. And those times when you really let down your hair are quite few and far between in anybody’s life. It’s unfair that the cinema verite filmmaker somehow gets faulted or put on a scale of how intimate the stuff was that he really got.

JOHN: There’s a difference between the situation you were in and the situation I was in. You had seven people to relate to and it would have been very unwise to get involved. Whereas with Lance, in some sense, I could say to him as a friend that I thought… well, I could take sides more. I could relate to him more as a person.

ALAN: Would you give him money or help him out if he were a bad spot?

JOHN: Yes, I did.

ALAN: Did you feel that was a moral decision? Moral is maybe too serious a word, but did you feel that was a decision in terms of changing or altering your role?

JOHN: I thought it was a moral decision rather than an aesthetic one. In how much money I gave him, I had to exercise some judgment. I was conscious that it could easily get out of hand and drastically change our relationship. Lance was stuck on the farm in Denmark, and I had a car. We took him to town a lot, picked him up. But I felt not doing that would have been unreasonable.

ALAN: When he was thrown out of the house, he came to us and told us, “Now look, I’ve been thrown out of the house by my mother. I can’t go back. I really have to leave Santa Barbara ultimately, but what I would like to do now is move in with you.” There was space for him to live with us for however long it would take for him to get it together to leave, but we said no. “We’re sorry. We’d like to, but you’ve just got to do it on your own.”

JOHN: I can understand that. I probably would have done the same thing. Even if he had been stuck with his last dollar, I never wanted to get into the position of being his sole means of support. I would take him out for dinner some of the time. For going to Paris, I actually loaned him the money to make up the difference between what he had and the fare. He didn’t have quite enough for the fare. And I knew it was a question of doing that or not going to Paris, and missing all that might ensue there.

ALAN : Was that a decision you made yourself without talking to Craig?

JOHN: Yes. I knew I was going to be called back soon because there was nothing new I could tell Craig was happening in Denmark. We’d been shooting the same thing for three or four weeks and I knew I was going to be called back. Whereas if we went to Paris.

ALAN: And you probably wanted to go to Paris?

JOHN: I wanted to go to Paris, sure. So that decision manipulated the situation only to the extent that you saw Lance in scenes that you wouldn’t have seen otherwise. I could do that in ways that you couldn’t because it would have been sudden death to get involved in the middle of the entire family. But when Lance was being screwed by other people, I could tell him I thought he was being screwed.

ALAN : Did you feel though, given the nature of his personality, he began to try to take advantage of you?

JOHN: Well, I felt that was always a possibility. In whatever I did, I was conscious of that. I still am. But I liked Lance very much and we had an enjoyable time together.

ALAN: He is pretty unique. In terms of the Santa Barbara location and the trips that we made, we really did try to be as inoffensive as possible in terms of our presence. A lot of the time, we could have acted more forthrightly and said, “Let’s do this today “or “Why don’t we go there?” It may have yielded some interesting scenes and had we just done that, I think it would have been O.K. But it would have been too confusing with that many people.

SUSAN: The minute you ask them to do something, they’ll begin to look to you again in the future. They’ll depend on you to direct them, and that’s not what we wanted at all. Even in terms of keeping up with them, we never asked them to slow down and wait for us. We just huffed and puffed along.

ALAN: We missed a lot of stuff. There were times when I would have liked to have been able to control situations. But I just knew, ultimately, that for what I’d gain, I’d lose in the end anyway.

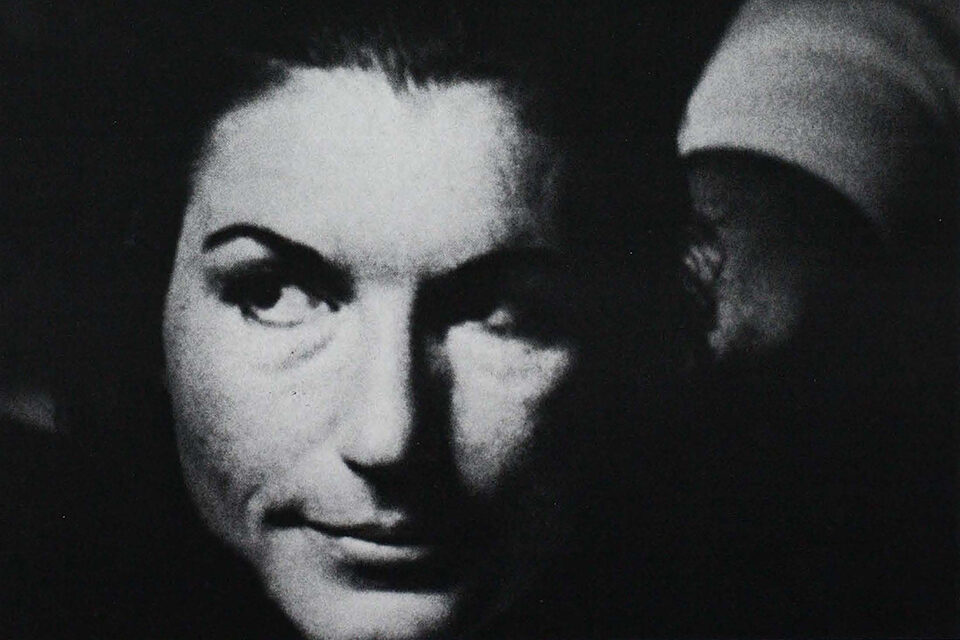

Pat Loud in An American Family (1973)

JOHN: Why did you choose to shoot the scene where Pat tells Bill to leave with her back to the camera?

ALAN: We knew that she was going to ask him to move out, but we didn’t really know when.

SUSAN: Not just when but was she really going to do it?

ALAN: Was she going to do it? Would she do it on camera? You would think she would do it late at night. She would cool it long enough for us to depart, then she would hit him with the information. It was very unpleasant filming that. When he walked in the door, she was sitting in a room that she rarely sat in. When he walked in, I realized that there was going to be some exchange. I just didn’t want to be there. I didn’t want to be filming it. I didn’t want to, for the sake of the job, bully my way through that scene. It occurred to me that I couldn’t step into that room. I was almost paralyzed with feelings of intimidation. As a matter of fact. Susan didn’t want to go in the room either and I had to actually shove her in because I knew that the sound had to be recorded. Pat had, in a very uncharacteristic gesture, turned all the lights off in that room so I had no exposure. Fortunately, I had a light taped to the handle of the camera which was a sun gun that I’d been using to shoot at the airport. I flipped that light on which meant I actually did the scene under the sun gun. That only added to the gruesomeness of the event.

I felt bad for Bill. We had been on that trip with him that he had come home from. It was a strip mining trip and a real grind. He had gone on a week or so more than we had spent with him. On the first lap of the trip, we drove from Los Angeles to Tucson, which is a thousand miles, in one night during an electrical storm. And he had kept up that pace. So he was really disoriented. It’s evident later on when he gets on the phone; he doesn’t know what time it is. He makes these pathetic calls. I just didn’t want to be there.

JOHN: I can understand that. I think what you do see is remarkable. I just wanted to see Pat’s face.

ALAN: Well, interestingly enough, there is that very brief bit where Bill gets on the phone and I go down the hallway, and just for a fraction of a second, peek around the door jam. Pat was sitting on the bed, crying. I don’t know if it’s clear that she’s crying. Then I immediately withdraw, so I’m sure the actual shot of her there is only about a foot long. Then Bill walks through the house and makes that incredible statement about “I’m expecting this call….. She has her back turned again. Then we accompany Bill out to the car and he drives away. I, at that point, decided to go back into the house with the camera running, hoping that something would be happening and we could just walk into it without really making it clear we were shooting. You know, the old camera-on-the-shoulder and you’re really shooting but you’re making like you’re not. I remember walking through the house; she wasn’t in the house. I just walked through this empty house looking into rooms. It’s a great shot. When we saw it in tile rushes, everybody said, “That really says it, the empty house.” That shot was eliminated.

SUSAN: I just think it’s interesting that we chose, and I don’t know why we chose, to keep following Bill even though the conversation was over. Instead, we could have turned off. But why did we keep following him? I find that an unanswerable question.

JOHN: I find that a little brutal.

SUSAN: Yes. That’s why I keep saying “Why did we do that?”

ALAN : The next day, I took those shots through the window of Pat lying by the pool. She’s in sort of a fetal position in a pink swimsuit and playing that muzak Santa Barbara station, which she did listen to and was actually listening to that day. It wasn’t laid in on the sound track. That’s the kind of thing in cinema verite where you really are crossing the line. You are like those guys in Italy who hide in the bushes to shoot Jackie Kennedy. I had that feeling.

SUSAN: Some part of you just shuts off, and you keep filming. It’s automatic.

ALAN: It’s a matter of being a professional. You just say to yourself, “Well, there’s the ups and the downs on these jobs.” You realize, I guess, that if you don’t film it, someone’s going to complain. We did stop after she threw him out of the house for a couple of days. All along, without having to make it a formal question and answer approach, we would always sense when one individual was tired of having us around. Then we would shift the emphasis and go on to another character.

An American Family (1973)

How do you feel about this style of filmmaking where the editor/producer is a separate person from the filmmakers?

ALAN : It’s very schizophrenic. Pennebaker once said that it was like two people painting a picture. You can do it but it has its problems. The series is edited chronologically with very few exceptions. There isn’t much that’s done internally within the scenes to alter them. I can’t think of one scene the tone of which has been changed by the internal editing. What you’re talking about is selection. Whose perceptions were entering into the choosing of the scenes? It really requires talking about Craig and his personality. It’s fair to say that he’s older than we are, and that his interests lie primarily with the relationship between Bill and Pat. Although there was a lot of footage involving the children, he never was that interested in them. He tended to dismiss them as “Oh, just kids,” with the exception of Lance. What you have is an imbalance in the amount of screen time each of the members get. Throughout the twelve hours, you almost overwhelmingly get the Pat and Bill story coming back again and again.

I think ultimately, that was a mistake. As an immediate structural device to make sense out of the footage and to sell it in the big sense, all that stuff with the divorce worked out well. It didn’t work because, as the audience started watching show after show, they became aware that there were other members of the family besides Bill and Pat that were as interesting. And they weren’t getting that material. And I maintain, it’s not because that material didn’t exist in the rushes—you have to believe me that it did—but because Craig wanted to structure it around the divorce. What’s wrong with that in terms of the Margaret Mead kind of overview of the series, the sociological viewpoint, is that Bill and Pat are basically fixed personalities. I don’t think they really changed that much. It’s true, they got divorced and Pat, maybe now, is living a different life. But their whole lives, their attitudes, their morals, their culture was formed years ago. They’re products of some other decade, whether it be the ’40s, ’50s, or even ’60s. The kids are not. They’re different. And if you are looking at the series as any kind of statement about society, then the kids have to be considered more important.

What did you film that would have been very revealing of the children?

ALAN: High school, for example, was eliminated. I know there were zillions of hours shot at the high school. The classes were unbelievable. Classes in leadership qualities! These bizarre California- type classes! What I’m saying is that not only was there a generational difference between the children and Bill and Pat, but there was also one between Susan and I and Craig. Craig’s view of life is a pessimistic one. He’s the kind of person who reads those books called Surviving the Seventies, and What Does It All Really Mean?, and Where Are We Now That the Bomb Hangs Over Us All? It’s not that he’s right or wrong in his view of society, but he has limitations. JOHN: The fact that he did it and he got it on the air, kinds of reality that had never been on the air before, was very important, whatever his biases were. The later shows were plainly better shows. If all the shows had been as meaty as some of the later ones, we just would have seen a lot more.

ALAN: But twelve hours is a lot of air time. There were a lot of different ways he could have structured it. You don’t get much of a sense of Bill’s business. Delilah had a very serious love affair with Brad. There was whole subplot of her getting birth control pills. There was material with the boys showing their attitudes toward their girl friends that was very revealing. Craig couldn’t ever really see it. He’d just say, “Ah, it’s a date.” Like, once when we called him and said we thought we had a really great scene with Grant and some of the boys building a sound stage in a garage where they could record. They were trying to saw the wood and it took them eight hours to put up one post and even that was short and crooked. I knew as he was listening, he was going, “Yeah, right. But what’s the latest? What’s the scoop? What’s the Rona Barrett news?”

SUSAN: All we saw in John’s footage of Lance’s summer vacation was that he was broke, worried and depressed. All the scenes that we saw, with the exception of the woman on the bridge and the cafe thing—and, even there, he gets put down—showed Lance having a miserable time. Now, I don’t believe that he spent five weeks on vacation and had a miserable time every day. But that was the impression I got from the footage in the final shows.

JOHN: Some of it was pretty dreary. In Denmark, we stayed three weeks or more. The last week, Lance went into town every night and had a great time. He burned himself out having a good time because he had had such a bad time up until then. There was material of them talking about that that brought it out. But it would have been very hard to film in the bars and places he was going without completely altering the scene. The concentration on money was overwrought and perhaps overly pessimistic, too. But Lance did have a dreary time.

Were you around for the screening of the three hundred hours in New York? Did you often confer with the editors?

ALAN: No. During the time we were filming, the rushes were looked at but we rarely got to see very much. There were no discussions being held at that time, anyway. When they came back to New York, it was rescreened straight through. We were called in from point to point to look at versions of the different shows, and to get that what-do-you-think kind of reaction. We would say what we thought was good or bad about them. I never got the feeling that Craig was interested in altering them, based on what we had to say. He just wanted to get some reactions to them.

But you also must remember that there was a certain commitment of time. We had worked every day for close to eight months on the shooting, and it’s questionable whether or not we really would have been prepared to then spend another year editing. I don’t know that I would have done it, even had the option been open.

SUSAN: We were living their life completely. I can’t stress that enough. We couldn’t even plan when we wanted to eat. Imagine what it’s like to live according to someone else’s schedule for eight months! When we finished, we felt a little like soldiers returning to civilian life. We almost had to learn how to plan our own lives all over again.

What was Craig’s involvement with you while you were shooting?

ALAN: A lot of people didn’t have that much location experience and didn’t really know what was expected of them (what they could and couldn’t do) including Craig. There was a confusion for a while when the producers felt the production was getting out of hand because Susan and I were sort of running it. If Craig or anyone else wanted to come up to the Loud house, we would say they couldn’t come because we were filming. Whether or not we were wouldn’t matter. It was a good way to keep them from coming up. The reason for this was that some people had decided that if they couldn’t be filmmakers, they would become characters in the film.

SUSAN: Craig was not there during the first three months because he was dealing with financial problems in New York. When he did show up, he thought he was going to go on location. While we were film ing at the house, he’d be over in a corner drinking a glass of vodka, just standing there.

ALAN: He has a heavy presence. He also developed a finger-snapping routine.

SUSAN: When I told him to get out of the way, he would go like this. [She stoops behind a table, her eyes peering over the top, intensely rolling her eyeballs.) He’d think that he’d be hiding. You’d just see his head over the tabletop. It was very distracting.

JOHN: It is to Craig’s credit that, whatever his inclinations may have been about that, he did give you ultimate responsibility for what to film and what not to film.

ALAN: But he does now take credit for being there all the time. He’s said to many publications that he was there daily. He also takes credit for shots that certain reporters liked. He takes credit for lighting effects. He wants everyone to know that he made the whole thing. He’d always refer to us as the production crew. We were a little bit more than a production crew!

SUSAN: But in certain ways, he was terrific. He gave us full freedom to do whatever we wanted. We had an enormous quantity of film; we had no restrictions on that.

ALAN: It’s really to his credit that he never did sit around saying, “Can’t you light it better?” He might have said, “Oh my God, I’m spending a million dollars and what we’ve got here is some elaborate home movies. We’ve got to make it look like a classier production.” He never thought along those lines. I don’t think he once made a comment like that.

JOHN: And the fact that, ultimately, he did get out of the house at your request.

ALAN: His being in the house was only for a very brief period. And as I say, it was a very confusing period when everybody finally assembled in Santa Barbara.

JOHN: Do you think the production was top-heavy in that sense?

ALAN : Absolutely. There were just too many people out there. Three people can make a movie. Even two people.

JOHN: I wished for a third person sometimes. You often need someone who can drive and do some of the carrying. There were some great scenes getting on and off the train but we couldn’t stand there and shoot—we had to get on the train.

As you came to know the Louds better, I imagine that you developed a view of them that they didn’t necessarily have of themselves. But yet you still had to relate to them every day when you weren’t behind the camera.

SUSAN: When you’re going to make a film about someone and you’re going to have to spend a lot of time with them, you have to like them. I understand all the criticism of the Louds and their life. But if you’re going to know somebody, you have to know their weaknesses and their good points. You have to understand how they came to be what they are. You have to be compassionate, forgiving, and loving.

ALAN : That’s a difference between this project and some of the other cinema verite films in the past. When you are filming a celebrity or someone who’s in the public eye, it’s different. I don’t think the Maysles in many of their films, maybe including Salesman, felt any kind of kinship with the people they were filming. In those films, you get much more of the feeling of the observer-subject relationship. In An American Family, I hope you feel that changed somewhat. Here, no one was so important or had an idea of himself as an impenetrable personality. Here, we were able to feel that the filmmakers were more or less on the same wavelength as the people being filmed.

SUSAN: We’re still in very close contact with the Louds. I was very emotionally involved with them. I’m really fond of them. I had a very tight relationship with all members of the family. Since the filming has stopped, we have kept up these relationships, which I’m really pleased about. What’s happening to them now is just as fascinating anyway.