By Richard Peña in the July-August 2009 Issue

Fringe Treasures

Two essential sidebars yield standouts both old and new

Each year Cannes feels bigger and even more overwhelming. As they keep upping the number of films and sections, you feel like you’re missing more with each edition. The past few years have witnessed the expansion of the so-called Special Screenings, while Cannes Classics has now become one of the essential festival sections.

From the July-August 2009 Issue

Also in this issue

Special Screenings this year harbored at least one terrific film: Min Ye (Tell Me Who You Are), the long-awaited new film by Malian director Souleymane Cissé. For many critics the finest of all African filmmakers, Cissé has regrettably only made six features over the past 30 years, yet each is wonderfully crafted and thematically provocative. Min Ye explores the contemporary costs of African-style polygamy—but then takes an abrupt turn into searing melodrama as it focuses on the emotional war that erupts between a filmmaker, Issa, and his first wife, Mimi.

A high-ranking bureaucrat, Mimi drifts into an affair and eventually demands divorce from Issa; in an attempt to destroy her, he files a grievance based on her alleged infidelity. Rarely has an African film featured characters as richly drawn, or beautifully acted as these; Cissé is not interested in presenting them as archetypes, but as complex and contradictory individuals. Min Ye is the best African film to appear in a while—and it’s a mystery as to why it wasn’t included in one of the more high-profile sections.

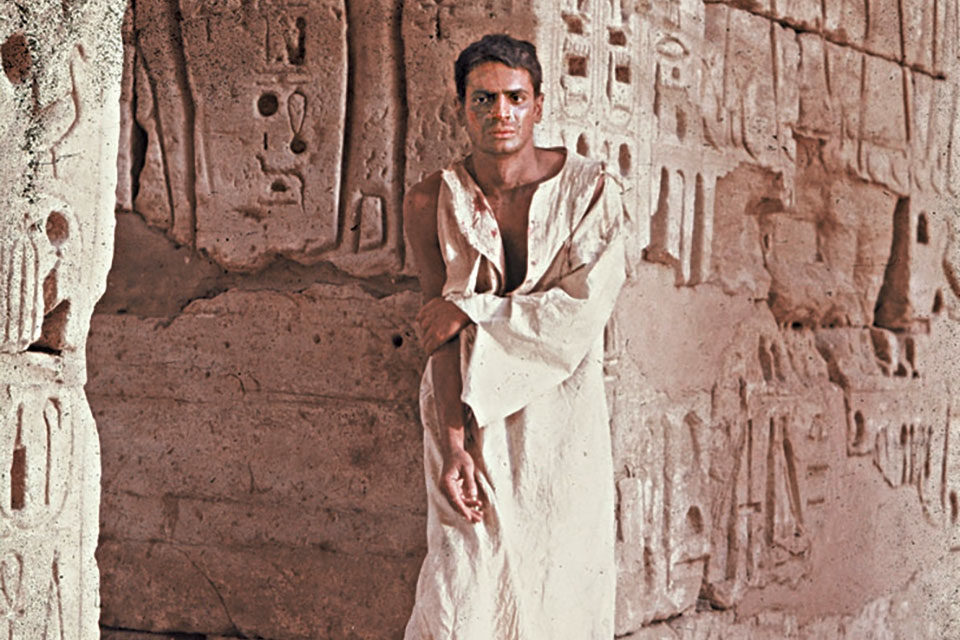

Al-Momia

For most of the years I’ve attended Cannes, scant attention has been paid to film history; while Venice and Berlin would each year mount major retrospectives, Cannes with few exceptions focused on the contemporary. But the arrival of Institut Lumière programmer Thierry Frémaux marked the beginning of a platform in Cannes for newly restored works. Now called Cannes Classics, this section included 20 films this year, ranging from the late Edward Yang’s 1991 A Brighter Summer Day to the fascinating 1967 antiwar compendium Far from Vietnam. But the great event was the unveiling of the marvelous restoration of Egyptian filmmaker Shadi Abdel Salam’s 1969 Al-Momia (The Mummy, aka The Night of Counting the Years). An indisputable masterwork, Al-Momia is set in 1881 in the land of the Horbat, a tribe long isolated from the rest of Egypt. Their leader has just died, and his two sons and heirs now learn the source of the tribe’s sustenance: a hidden cache of sarcophagi filled with gold, jewelry, and other treasures that are sold to black marketeers. The two sons are repulsed to learn that their tribe has survived by robbing tombs; and the younger one, Wannis, eventually reveals the hidden location to an emissary of an eminent archaeologist, who then starts the process of removing the material to Cairo.

Fascinating on many levels, Al-Momia is in essence about the origins of Egyptian national identity. A nation under foreign domination from the 4th century B.C. up until 1952, Egypt by the late 19th century was already reacting to ideas about nationalism that had earlier swept Europe. Connecting to the pharaonic past was one way of becoming “Egyptian.” Yet this nationalist project also entails the destruction of the Horbat as a distinct group. The film details the beginning of the tribe’s assimilation into Egyptian mass society, and Wannis’s flight at the end expresses his horror at what his actions have wrought for his family and his tribe.

Beyond its political and historical context, it must also be said that Al-Momia is astoundingly beautiful. Abdel Salam shot all his exteriors between 4 and 6 a.m., or 4 and 6 p.m.—times that mark the transitions between day and night. This gives the film a kind of ethereal quality, as each image feels as if it’s just about to disappear. Formerly an art director (he worked closely with Kawalerowicz on his 1966 film Pharaoh), Abdel Salam creates incredibly striking images, juxtaposing the gaunt, black-robed Horbat with the endless, craggy moonscapes they call home. All the dialogue is in Fusha, or classical literary Arabic, which lends a certain ritualistic air to the action, since it is generally used only for matters of great importance.

Profound thanks to the Cineteca di Bologna, which undertook the restoration, and to Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation, for allowing this masterpiece to be seen and discovered once again. If it had been the only film screened at Cannes, 2009 still would go down as a great year.