Festivals: Toronto

See our November/December issue for reports on the Toronto festival by Gavin Smith and Nicolas Rapold.

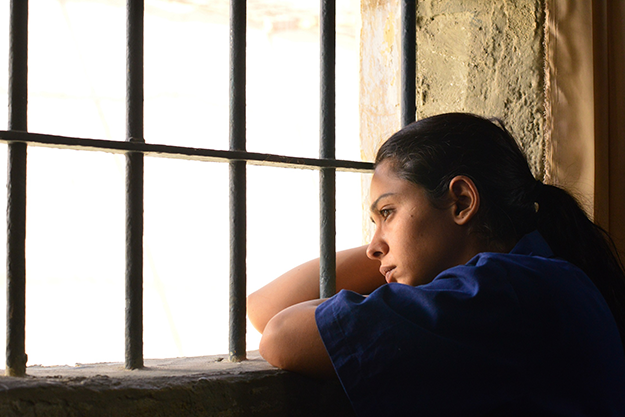

3000 Nights

Mai Masri’s drama 3000 Nights begins as Palestinian schoolteacher Layal (Maisa Abd Elhadi) lands in an Israeli jail, accused of abetting a juvenile bomber. Once inside, she withstands cruelty from the female warden, guards, and fellow prisoners, including a pitiless reception by some of her Palestinian cellmates. And that’s all before she realizes she’s pregnant.

Years pass—the title denotes Layal’s extravagant sentence, despite flimsy evidence of guilt—during which the authorities use her son Nour as collateral, buying her docility and even her complicity by allowing her to raise him behind bars. But things shift across 3000 Nights, with a winching implacability familiar from modern lockup classics like Hunger (08) or A Prophet (09). Gradually, the jailed Arab women, some male staffers, even some of the Israeli convicts unite in solidarity against a system oppressing them all. As that happens, Layal questions whether individual comforts, including access to her child, should trump other political, moral, and collective obligations that might entail relinquishing Nour.

Questioning the sacred natal bond is a huge risk. After all, Lenny Abrahamson’s Room, a very different story about incarcerated motherhood, would likely not have secured the Grolsch People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival without vigorously sanctifying the life-giving codependency of parent and child, after a brief flirtation with critiquing it. Despite or possibly by dint of posing thornier questions, 3000 Nights played three times to packed houses at TIFF, prompted lengthy and effusive Q&A’s with Masri (an acclaimed documentarian making her debut in fiction film), and was acquired mid-festival by the Egyptian-Emirati distributor Mad Solutions. Even better, this level of excitement extended to many other Middle Eastern and North African films in Toronto, whose formal and thematic risk-taking escalates each year, even as their audiences grow visibly larger and more diverse.

Credit for this welcome surge of attention goes in part to adventurous scouting and energetic outreach by programmer Rasha Salti, who has curated TIFF’s selections from these regions since 2011. The prime movers, however, are the artists themselves, employing styles and tones all the way from urban realism to brazen experimentation in romances, comedies, action thrillers, documentaries, and historical as well as contemporary dramas. Along the way, at their centers or margins, these films take provocative looks at sex work, torture, trafficking, homophobia, censorship, and multifarious abuses of power. Even three or five years ago, movies from the Middle East and North Africa would likely have broached these topics with less narrative daring and formal brio, if they confronted them at all.

As I Open My Eyes

Especially noteworthy at this year’s festival was how many features from this part of the world were directed by women, or at least privileged women’s stories. The Tunisian-French As I Open My Eyes, which won two prizes at Venice during its Toronto run, follows a teenage doctor-in-training named Farah (Baya Medhaffer) who drifts from her studies and prioritizes her role as lead vocalist in an underground rock band. The film takes its name from one of the band’s signature songs, chronicling the inequities they see everywhere in Tunisia, on the eve of the 2010 revolution. Authorities react as well as you might expect. That said, director and co-writer Leyla Bouzid, daughter of envelope-pushing Tunisian auteur Nouri Bouzid, refuses to idealize dissidence. Farah, prone to impetuous narcissism in matters public and private, frequently puts herself and her mates in harm’s way, possibly trusting her class privileges to protect her. Her mother Hayet (Ghalia Benali, a prominent Tunisian singer giving one of the festival’s best performances) discourages Farah’s choices of art over science and rebellion over orthodoxy, but she is no cardboard antagonist. This richly photographed, sonically entrancing drama—a plausible hit with U.S. art-house audiences, if any distributor takes the chance—affords complexity and nuance to every character, without pulling punches about flagrant villainy.

Price of Love

Price of Love, directed by rising Ethiopian star Hermon Hailay, does for Addis Ababa what As I Open My Eyes does for Tunis, encapsulating the audiovisual enticements of an eclectic city without exoticism or airbrushing. Young taxi driver Teddy (Eskindir Tameru), haunted by his mother’s death and saved from gambling and drink by a local clergyman, intervenes one night to protect an imperiled prostitute named Fere (Fereweni Gebregergs), whose pimp retaliates by stealing Teddy’s cab. What ensues is both a romance and a rivalry: Teddy strives to help Fere but resents how his altruism keeps putting him at risk, as when his spiritual mentor renounces Teddy at the first sign of backsliding into that same, seamy ecology of hookers and thugs that prematurely claimed his mother. In its way, Price of Love reiterates the paradox of 3000 Nights, advocating camaraderie across lines of difference but admitting the huge personal tolls that new ideals or alliances can extract. Even as melodramatic incidents accumulate, the musical score favors light jazz over broody strings, framing the characters’ stark conundrums within an idiom of improvisation. Teddy and Fere are just two folks trying to get by, making the best choices they can like everyone else in Addis, even as the stakes of joining or separating, staying or leaving, even living or dying continually mount.

Much Loved

This tension between individualism and group identity manifested in the program itself, given the attendant gains and losses whenever distinctive concerns and styles of, say, Ethiopian, Palestinian, Lebanese, Tunisian, Algerian, or Moroccan films are folded together as “Middle Eastern and North African.” Even within national traditions, diversity manifested: the jewel-toned colors, bucolic eroticism, and mercurial editing of Hiwot Admasu Getaneh’s short film New Eyes bear little in common with Price of Love’s darker, grainier realism, but each woman’s vision feels essential to whatever “Ethiopian cinema” currently connotes. Meanwhile, the work of Masri, Bouzid, and Hailay furnished useful frames of reference for films like Dégradé (directed by Tarzan and Arab Nasser) and Much Loved (by Nabil Ayouch) that had played at Cannes but deserved more attention, suggesting some linking threads while showcasing, by contrast, unique dimensions of each project. Dégradé, another stimulating debut, traps 13 fractious women in a stifling beauty salon, hiding from outbursts of violence in the streets of Gaza, and subject to each other’s taunts. In the astonishing Much Loved, an intrepid quartet of Moroccan brothel workers increasingly depend on each other’s support as they tangle with judgmental families, closet-case johns, regionalist prejudices, insatiable but penniless obsessives, and other risks endemic to their profession. The fearless script finds the prostitutes chortling at Saudi oil magnates and their hunger for adulation. At least the Saudis tend to have the most cash in their pockets—and are thus ripe for pickpocketing after they’ve exhausted themselves in bed.

The Society

It says a lot that Much Loved, so politically thorny, so sexually explicit, so swiftly banned in Morocco, had fierce competition as the bravest film in Toronto, even within this program. In the Iraqi-German short The Society, directed by Osama Rasheed and surely the screen’s first treatment of gay desire in Baghdad, the kind of collective solidarity evinced in so many features is, at best, a far-off dream. Alternating silky and crude black-and-white stocks, interrupting its wisp of a narrative with searing testimonies by actual gay Iraqis, The Society is an eloquently broken-backed object, a series of shards on its way to being a film—exactly as its subject requires.

Starve Your Dog

Finally, none of these films prepare you for the formal and rhetorical audacity of Hicham Lasri’s Starve Your Dog, a cherry-bomb of political anger rendered in hard digital images and gangrenous colors. Commencing with a direct-to-camera tirade about present conditions in Morocco, voiced by an elderly woman who expects to be killed for speaking up, the movie builds slowly to its narrative crux: an interview between a journalist named Rita (Latefa Ahrrare) and the aging Driss Basri (Jirari Ben Aissa), an infamous executor of state-sanctioned violence against Moroccan citizens for almost 20 years. Imagine Death and the Maiden rebuilt as “gotcha” journalism, or Katie Couric settling in to grill Robert Mugabe but as a cultural insider with her own wounds to nurse. The content and tone of Starve Your Dog—which cross-cuts several times to Basri’s deranged and homeless daughter, exposing herself to strangers on the street for a few coins—are so livid that the camera itself enters a crisis state. With canted angles abounding, and several images beveled into hall-of-mirrors reflections of themselves, Starve Your Dog feels jagged and hot to the touch. It’s the second film in a planned trilogy by Lasri; the mind reels as to where he might proceed from this discomfiting but urgent spectacle. When he completes that third film, I place my bets on Salti to exhibit it. As we collectively open our eyes to more Middle Eastern cinema, Toronto keeps emerging as an essential place to look.