TCM Diary: Stars Behind Bars

Ladies They Talk About

Roger Corman may have proved it was possible to merge any vaguely feminine noun with “Caged” or “Chained” and be halfway to a grindhouse bonanza, but the women in prison subgenre (WIP to those so invested as to require the abbreviation) wasn’t always the vanguard in exploitation cinema. At first it was a strain of melodrama that detailed the plight of young women straying from the righteous path (read: falling for the wrong men). As often as not, the heroine was rehabilitated in stir and released into the arms of a better prospect—sometimes even the crusader who put her away. The moralistic flavor and jejune belief in the reformative power of correctional institutions were offset by gutsy star performances and (especially before the Code) dialogue rife with double entendres.

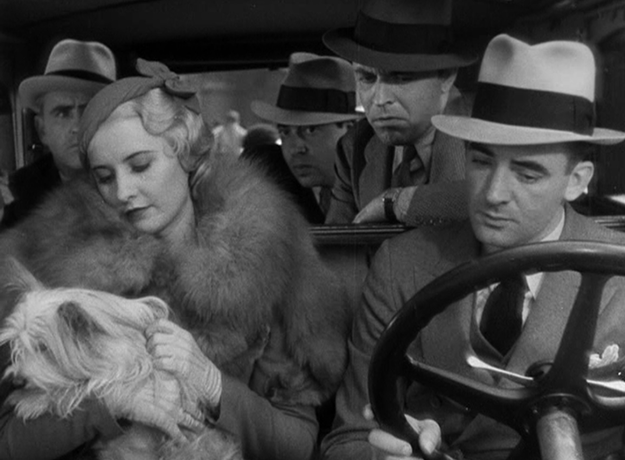

The standard greeting of fresh arrivals with a cry of “New fish! New fish!” is a staple of all prison dramas, but induces a particular cringe in the distaff versions—perhaps it’s something to do with the minnow-to-shark disparity. Like most WIP clichés, it likely first appeared in Howard Bretherton and William Keighley’s 1933 Ladies They Talk About, one of the earliest illustrations of the genus (coming as it did just three years after The Big House, the granddaddy of all jailhouse movies). The main lady they talked about was Nan Taylor—played by Barbara Stanwyck at her youthful peak—a gun moll condemned to San Quentin for acting as decoy in a successful bank heist. As a new fish, she’s led around the yard by veteran inmate Linda (Lillian Roth, the troubled singer-actress hauntingly incarnated by Susan Hayward in the biopic I’ll Cry Tomorrow), who instructs her that the two things the cons desire most—freedom and men—are just a few feet away, but always out of reach.

Otherwise, if truth be told, the prison looks like a country club. The women, who comprise a colorful cross-section of types and personalities—from “Aunt Maggie,” busted for running a “beauty parlor,” to society murderess Mrs. Arlington, who bemoans the “servant problems” behind bars—have no difficulty procuring pets, non-regulation nightgowns, and even musical instruments to help pass the time. In one deliriously sure-why-not sequence, Roth croons a love song to a photo of satchel-mouthed comic Joe E. Brown, later immortalized as Osgood Fielding III in Some Like It Hot. (It’s unclear whether this was because Brown was also contracted to Warner Brothers at the time, or if Linda had begun to go stir bugs—or if it’s simply that nobody’s perfect.)

Ladies They Talk About

Preceding the restrictions of the Hays Code and camouflaged by its genre origins, Ladies They Talk About was free to address racial and sexual identity with startling candor. A scene in what can only be termed the break room finds a cigar-chomping convict flexing her muscles for the benefit of another inmate, acknowledged by Nan with a knowing “Mm-hm.” More complicated is the character of Mustard, played by actress Madame Sul-Te-Wan (discussed by Ashley Clark in a July/August 2016 Film Comment article on early black performers). The prisoner in charge of laundry, Mustard refuses to return Mrs. Arlington’s apparel until she gets the items promised to her—regrettably, bleaching cream and hair straightener. But the scene’s fascination owes to Mustard’s awareness that, incarcerated for life, no further penalties can be incurred (“I’m not afraid of nobody in this jail! I’m doin’ life and that’s all I got!”). As such, there’s no need for her to act subservient, and so she treats fellow cons and matrons as equals. The fact that she feels compelled to use products to erase the racial signifiers that she refuses to see as handicaps makes the character a multitude of contradictions worthy of Whitman.

By 1950, the social melodrama had evolved into the cinematic cri de coeur, with the shrieks and shadows of postwar noir accenting the brutal conditions in need of redress. Following on the heels of the 1948 women’s mental ward chronicle The Snake Pit, John Cromwell’s Caged sought above all to reform the underfunded state prisons’ reliance on disgruntled and sadistic staff who treat inmates as subhuman, attending only to their subjugation and punishment. Embodying the rotten fruit born of institutional failure is Matron Evelyn Harper (Hope Emerson), a hulking sociopath who stands six-foot-two and passes between the lines of convicts like a malignant tank.

Actress Emerson was profiled in the May/June 2015 issue of Film Comment, which called Harper “a snarling sicko (‘Pile out, you tramps!’) who lives in a cell of her own, adjacent to her charges like a drill sergeant, with a needlework sampler on her concrete wall made by one of her girls: ‘For Our Dear Matron.’” Emerson may have been parodied by John Candy in the SCTV sketch “Broads Behind Bars,” but there’s no levity in her performance here. She is the stuff nightmares are made of, a woman whose arresting physicality is merely the hull for her utter void of compassion. Politically connected, Harper has held onto her job despite the best efforts of the humane superintendent (Agnes Moorehead, uncharacteristically subdued). Swilling gin in her quarters, advocating the rubber hose method of behavior modification, torturing her charges with talk of her “man outside”—knowing that their worlds contain no men and no outside—Harper is as despicable as Hume Cronyn’s vicious captain of the guards in Brute Force.

Caged

The protagonist of Caged is 19-year-old Marie Allen (Eleanor Parker), and to the film’s credit, her arrival does not disrupt or even affect the prison ecosystem—she’s just another new fish in an overstocked stream. Like Stanwyck’s Nan, Marie was peripherally involved in a holdup; now a widow with a child on the way, the timid Marie has none of the instincts or stamina needed for survival in Harper’s ward. Parker’s performance is brilliantly layered, registering quivering vulnerability in the early scenes (laid out on a slab for inspection as a nonchalant nurse checks her body for drugs), recounting the crime that led to her conviction in hushed tones, eliding the facts as though they’re too awful to consider (“I stayed in the car while he… and then…”).

Harper pegs Marie as a probable source of cash or perhaps sexual favors, and is at her most unnerving when outlining the quid-pro-quo prison economy to the petrified novice (“Let’s you and me get acquainted honey… Take this chair here, it’s kinda roomy”). Marie speaks little at first, but her wounded, watchful eyes register all. The events that serve to harden her from doe to tigress are not unexpected (having to surrender her child at birth, witnessing a fellow con’s suicide on denial of parole, her own parole board’s lack of leniency), but these scenes are rendered by DP Carl Guthrie with Langian Expressionism, marked by chiaroscuro lighting and canted shadows of prison bars. A shot of Parker grasping at a barbed wire fence anticipates the thematically related forward track in Gillo Pontecorvo’s Kapò that earned “the most profound contempt” of Jacques Rivette.

“This isn’t my first year away from home,” Marie sniffs around the two-thirds mark, and by now her breathy whisper has become full-throated and snide. Her entire mien is different; prison has changed her in deep-set ways, and Parker is hardly recognizable from the opening. (She and Emerson were both nominated for Academy Awards—this was likely the only women’s prison film to garner Oscar attention until Chicago, with its merry murderesses and Fosse choreography.) Though produced under the auspices of the Code, Caged covers everything from sexual bartering to recidivism and penal corruption with a frankness that inspires shivers and awe. It was adapted by former Los Angeles Times reporter Virginia Kellogg from her story “Women Without Men,” based on experiences while incarcerated for research, and she, too, was Oscar-nominated. The ice-cold noir ending, scored with bursts of jazz destabilizing in their incongruity, stresses the futility of systems that contain without attempting to rebuild, because convicts will exploit any end to return to a world from which they’re alienated—making for a woefully cyclical punitive treadmill. A powerful message to issue from the genre of The Big Doll House and Lust for Freedom.

Ladies They Talk About and Caged airs January 24 on Turner Classic Movies.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.