TCM Diary: Elvis, Actor

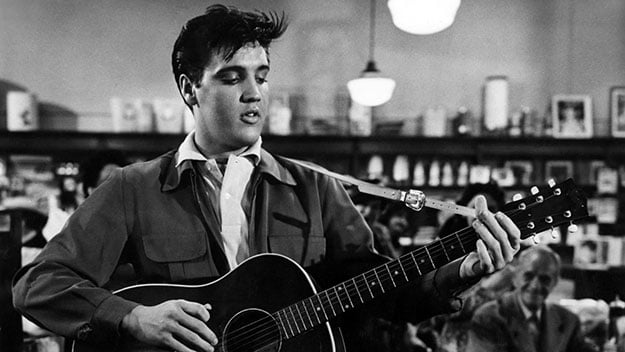

King Creole

In the opening number of 1958’s King Creole, directed by the great Michael Curtiz, Elvis Presley lounges on a balcony in New Orleans, singing a call-and-response song with the people hawking wares below. At one point, still singing, he picks up a comb, but before he runs it through his hair he casually flicks his fingers along it to clean it off. It’s a tiny moment, not dwelled upon, but it almost single-handedly grounds the film in reality. The comb is not a prop. It belongs to him. Good acting is made up of such details. When I tell surprised people why I think Elvis is a good actor, I tell them about that comb in King Creole.

In his autobiography, producer Hal Wallis describes the first time he saw Elvis Presley, making his national television debut on The Dorsey Brothers Stage Show, in January 1956: “[Elvis] wore a sport coat that was slightly too large for him and tight black pants. At first, he looked like any other teen-aged bopper, but when he started to sing, twisting his legs, bumping and grinding, shaking his shoulders, he was electrifying. I had never seen anything like him . . . I vowed nothing would stop me from signing this boy for films.”

Presley’s first film under contract with Wallis was Love Me Tender (1956). Mildred Dunnock, who played Presley’s mother, tells a story about his lack of experience. In one scene, it was written that his character grabs a gun and charges for the door, ignoring his mother’s cry to “Put that gun down!” On the first take, when Dunnock said her line, Elvis, one of the most famous mamma’s boys of all time, obeyed her. He put the gun down.

Love Me Tender

Dunnock’s interpretation is very revealing: “For the first time in the whole thing he had heard me, and he believed me. Before, he’d just been thinking what he was doing and how he was going to do it. I think it’s a funny story. I also think it’s a story about a beginner who had one of the essentials of acting, which is to believe.”

That’s a hell of an endorsement. Wallis had his own strong impression after watching Presley’s screen test: “I felt the same thrill I experienced when I first saw Errol Flynn on the screen. Elvis, in a very different, modern way, had exactly the same power, virility, and sex drive. The camera caressed him.” Errol Flynn is an apt comparison. Flynn exuded an effortless charming masculinity. It looked effortless, but try to walk across a room like Errol Flynn. Throw your head back and laugh heartily while you’re doing it. Try not to look ridiculous. Good luck.

Our first movie gods and goddesses—Rudolph Valentino, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich—were thoroughbreds of personality. There is variety to be had within established personae. John Wayne found limitless possibilities in his. Persona acting is often written off as “just playing yourself,” but Cary Grant, a master of persona, answered that charge: “To play yourself—your true self—is the hardest thing in the world. Watch people at a party. They’re playing themselves … but nine out of ten times the image they adopt for themselves is the wrong one.”

Tickle Me

Elvis was a persona actor. If you hold Presley up against Laurence Olivier or Claude Rains, then it doesn’t even seem like they are in the same profession. But it is the same profession. Presley had many natural gifts and he knew how to use them. He was dazzling to look at. He didn’t take himself too seriously. He had a gift for slapstick comedy (he does a pratfall in 1965’s Tickle Me rivaling the one Cary Grant does in the music room in The Awful Truth). Most importantly, he operated from a place of generosity. And generosity like that cannot be manufactured. Audiences feel it.

“Elvis movies” are a genre in and of themselves. They share similarities with equally distinct cultural artifacts like Esther Williams’ swimming extravaganzas, or Busby Berkeley’s musical numbers. They create their own category and can’t be compared to anything else. The majority of Presley’s movies were made during the 1960s, as the studio system collapsed. In an unstable era, Presley was the definition of a “sure thing.” They were made very cheaply, so the profit was enormous. Elvis was a money-generating machine. He made 31 films, spanning from 1956 to 1969. The three films after Love Me Tender—Loving You, Jailhouse Rock, and King Creole—were attempts to get a handle on the Elvis phenomenon, as well as fascinating experiments in persona-building.

Jailhouse Rock is the most purely entertaining of the four, although King Creole is the superior film, and the best film Presley made. In Jailhouse Rock, he plays Vince, a hot-headed guy doing hard time for manslaughter. After his release, he becomes a star. In the film, Presley’s hair is a towering pompadour, an aggressive externalization of his desire to be, in Dave Marsh’s beautiful phrase for him, “an unignorable man.” There are subtleties in the performance, like the shy kindness with which he treats the floozy who tries to pick him up in the first scene, or the thoughtful expression on his face when he listens to his cell mate sing. The erotic scene where, half-naked, he is tied up and whipped, armpit hair on display, brings “fan service” to new heights. So, too, the scene where Vince grabs Peggy (Judy Tyler, who, tragically, died in a car accident shortly after filming), kissing her violently. She snaps, “Don’t try those cheap tactics with me.” Presley drawls, “That ain’t tactics, honey. That’s just the beast in me.” He doesn’t swagger the line, the most obvious choice. Instead, he’s tipsy with carnality, lost in a woozy zone of unapologetic desire. He’s liquefied sex on legs.

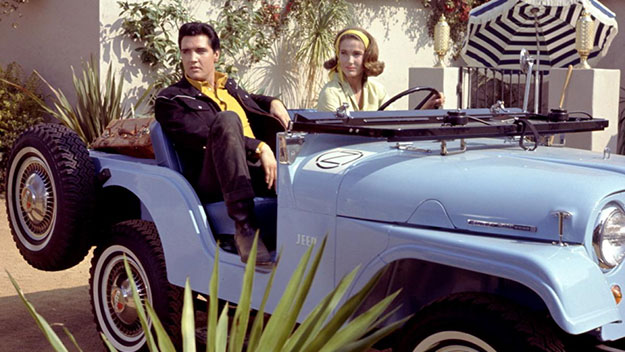

Blue Hawaii

What is now known as the “Elvis Formula Picture,” started with 1961’s smash hit Blue Hawaii. The “formula pictures” take place in an “exotic” location, although not a recognizably human universe. Elvis plays a singer moonlighting as a race-car driver, or vice versa. He’s triangulated by women. Mostly forgettable songs (with some exceptions) are plugged in at random. There is no social commentary. These movies are often totally ridiculous, but if you imagine watching them on a hot summer night at a crowded drive-in, they make perfect sense.

Viva Las Vegas (1964) is peak Elvis Formula. It’s the only film where he was put opposite a woman—Ann-Margret—of fire equal to his. Their scenes together smolder, spark. Presley rarely did duets but he does one with her here. In “The Lady Loves Me,” the two of them stroll around the pool, Elvis strumming his guitar, Ann-Margret playing hard-to-get in a yellow bathing suit. It’s an onslaught of blazing charm. In allowing her to be fabulous, in sharing the screen with someone as charismatic as he was, he is even more powerful and attractive. She makes him work, and he was always good when he had to work to stand his ground. It’s a shame the two of them didn’t do more films together. Oh well, we’ll always have Vegas.

In the final years of Presley’s contract, nobody was paying attention anymore. Sadly, some of his best movies come from this period. Many of them are not musicals, outside of the title songs. There’s a looseness to them, a roiling chaos lacking in the Elvis Formula movies. Presley is unleashed, his persona naturally expanding to include more eccentric shadings.

Live a Little Love a Little

The best of the bunch is 1968’s Live a Little Love a Little, directed by Norman Taurog. There is no reason this film shouldn’t be on any list of good ’60s comedies. Its nearly forgotten status is baffling. Presley plays Greg Nolan, a busy photographer, who gets caught up unwillingly in the crazy-making web of Michele Carey’s ditzy Bernice. Bernice takes one look at Greg and decides: I must have him. The film owes a lot to Bringing Up Baby, even down to the fact that it’s an animal that brings them together, Bernice’s gigantic dog Albert. (There are other nods: Presley racing around her house in a bathrobe because she has hijacked his clothes, and Bernice pretending to be a pre-recorded voice on the phone when he calls her, just as Hepburn did in Bringing Up Baby.)

Live a Little is not strictly a musical. Along with the title song, it features only two numbers, a psychedelic dream-sequence song called “The Edge of Reality” and the ferocious “A Little Less Conversation,” sung at a gigantic party at what is obviously meant to be the Playboy mansion. Many of the songs in the formula pictures are terrible, and so far beneath him that it’s vicariously insulting to listen to them (although he commits to these songs fully, evidence of his professionalism). But the two songs in Live a Little give him a chance to do some real singing. “A Little Less Conversation,” in particular, allows Elvis to do what got him famous in the first place: be a sexual dynamo. (Many of the “formula pictures” are quite coy about sex. Elvis is not coy here, and it’s a thrill.)

What makes the film so much fun—and an anomaly in Elvis’ movie career—is the tension between what Elvis’ character wants to be doing (get his photography career on track), and the roadblocks tossed in his way by Bernice. In his other movies, the “Elvis” character always got what he wanted: the main “conflict” was “Which one of these totally available scantily clad women chasing me around do I want? Maybe I can have all of them?” Here, though, he doesn’t want any of it. Throughout, he is irritated, cranky, unshaven, and frantic to get away from this screwball in go-go boots who won’t leave him alone. It’s such an unexpected sweet spot for Elvis, and it’s one of his best performances.

Live a Little Love a Little airs August 16 on Turner Classic Movies.

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. She wrote the narration (read by Angelina Jolie) for the Gena Rowlands tribute reel played at the 2016 Governors Awards. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.