Readings: After Afterimage

This article appeared in the August 4, 2022 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

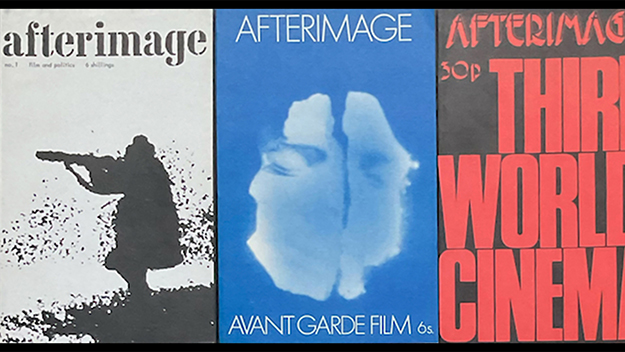

Courtesy of The Visible Press

The Afterimage Reader

Edited by Mark Webber, The Visible Press, 2022

If the 1960s ushered in new approaches to cinema, the decade was no less impactful for film criticism. Yet here in the United States, audiences are more likely to know the films of Kijû Yoshida, Glauber Rocha, and Harun Farocki than the names of the magazines they wrote for. In light of this, the appearance of The Afterimage Reader, published last May, is very welcome. Since 2014, the independent, UK-based Visible Press has released four outstanding titles collecting the otherwise scattered and hard-to-find writings of key figures from the international avant-garde, including American experimental filmmaker Gregory Markopoulos (Film as Film, 2014), English experimental filmmakers Peter Gidal (Flare Out, 2016) and Lis Rhodes (Telling Invents Told, 2019), and maverick American critic-filmmaker Thom Andersen (Slow Writing, 2017). If The Afterimage Reader is a departure from the press’s previous focus on individual director monographs, it offers something equally significant and rare: a selection of writings from the independent English journal Afterimage, representing a cross-section of its unique and inventive approaches to radical cinema.

Afterimage was founded in 1970 by Simon Field and Peter Sainsbury, then recent graduates of the University of Essex. The year before, Jean-Louis Comolli and Jean Narboni, co-editors of the French magazine Cahiers du cinéma, had published “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism,” a landmark manifesto inspired by the protests of workers and students that spread throughout France in the spring of 1968. The first issue of Afterimage makes no explicit reference to the Cahiers manifesto, though its cover—featuring a still from the militant anthology film Cinétracts (1968) and the words “Film and Politics” printed above it—gestures at the same question Comolli and Narboni had attempted to answer: what do we mean when we talk about radical cinema? Throughout its run, Afterimage considered many possible answers. One of the twin editorials published in its second issue, for example, favors the technical experimentation of avant-garde cinema, while the other is more concerned with political themes. However, underlying all of the journal’s investigations was the importance of recovering the “complex and interesting possibilities” of film form that throughout history have been underutilized and undervalued by commercial cinema.

Other journals would soon contend with similar questions, including the influential Screen, which produced the first translation of the Cahiers manifesto for its spring 1971 issue. For Screen, pursuing this question meant recruiting various intellectual frameworks, from structural linguistics to psychoanalysis, into a theoretical mode that tended to focus on classical Hollywood and European art cinema. (A 1972 dossier on Douglas Sirk, for example, marked an early attempt at semiotic analysis to elucidate the filmmaker’s ironic departure from the conventions of mainstream illusionistic cinema.) On occasion these same methods would find their way into Afterimage, particularly in its fifth issue, guest-edited by the prolific film theorist and frequent contributor Noël Burch. Yet on the whole, Afterimage’s approach was seldom inclined to any particular intellectual tradition. Rather than depend on a particular school of thought to illuminate ideas about film, Afterimage began with the films themselves, relying on them to lead the way to an answer and criticizing other English magazines, including Screen and Movie, for “merely retracing territories covered by their Continental forebears” and overlooking or dismissing new trends in filmmaking. Though its editors would not likely have seen themselves as bedfellows with André Bazin, their philosophy hewed close to one of his great beliefs: that cinema’s existence precedes its essence, and that we do better as critics (even radical ones) to meet films where they are rather than impose ideas of what they should be from the outside.

In practice, this meant that Afterimage opened its pages to a wide variety of films, past and present, without privileging a specific style or movement. The 13 issues of Afterimage published between 1970 and 1987 each singled out a unique topic: Third World cinema, independent British cinema, silent cinema, underground and avant-garde cinema, experimental animation. Each brought together an eclectic and unorthodox grouping of filmmakers—a breadth that, for the Afterimage editors, was crucial for the fulfillment of the journal’s mission. “Frampton and Godard may seem an unlikely pair,” Sainsbury noted in an editorial, “yet beneath the familiar ideological surface of things they meet in a concern to establish a cinema which does not seek to portray, reflect, interpret, symbolise or allegorise – but to enquire.” This open-mindedness allowed for an attentiveness to emerging filmmakers and trends that other journals often passed over. One of the most important aspects of Afterimage, yielding arguably its most enduring legacy, was the priority given to translating and publishing original writing by filmmakers, including Julio García Espinosa’s “For an Imperfect Cinema,” Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino’s “Towards a Third Cinema,” and Jean Epstein’s “On Certain Characteristics of Photogénie,” all of which made their English-language debuts in the journal. Equally important are the journal’s interviews, which introduced readers to a wide range of filmmakers—everyone from Philippe Garrel to Michael Snow, Klaus Wyborny to Glauber Rocha, Hollis Frampton to Derek Jarman.

Throughout its nearly two-decade run, Afterimage sought to discover a “counter cinema,” to borrow the title of one of its most famous essays, “Godard and Counter Cinema: Vent d’Est” by film theorist Peter Wollen, which is reproduced in the Reader. Wollen took Godard’s Wind from the East (1970) as one answer, favoring an agitational style that broke with the conventions of classical narrative. Later issues explored other possibilities—for example, the importance of the fantastic and the uncanny, inspired by the Surrealist works of Chilean filmmaker Raúl Ruiz and Czech experimental animator Jan Švankmajer, among others. Brought together in The Afterimage Reader, these approaches together represent an adaptive critical practice that sought to discover new ideas in new, divergent, and even incommensurate cinemas: the frenetic films of Stan Brakhage and the formally sober works of Straub-Huillet were, for the journal’s editors and writers, equally generative. In seeking a radical cinema today, we may benefit from the protean curiosity that Afterimage inspires.

The author would like to thank Jason Sanders and Sandra Garcia-Myers for their help in research for this article.

Jonathan Mackris is a writer based in California.