Kaiju Shakedown: The Man Who Stole the Sun

The Man Who Stole the Sun is a bona fide classic of Seventies cinema. It was ranked as the seventh-greatest Japanese movie of all time by the influential film magazine Kinema Junpo, and appears constantly on “Greatest Movie” lists from critics and directors (here it is on Satoshi Kon’s). Yet the 1979 film is criminally under-screened in the West. Like El Topo or A Clockwork Orange, it’s one of those rare movies that exists so far outside the boundaries of its chosen genre that there’s almost no other film to compare it to. Think Dr. Strangelove, only with more action; think Dirty Harry, except that the bad guy has a homemade nuke instead of a sniper rifle. Whatever you feel about this movie—and critical assessment ranges from “much too long . . . somewhat ridiculous” at the time of its U.S. release in 1982 to “…a truly singular work ripe for rediscovery” when it screened at the New York Asian Film Festival—The Man Who Stole the Sun stands alone.

The two-and-a-half-hour film was an independent production released by Toho and directed by Kazuhiko Hasegawa, whose mother was pregnant with him and living in Hiroshima when America dropped the atom bomb. It’s as if that in utero radiation poisoning seeps through every frame of Hasegawa’s film. You might think of The Man Who Stole the Sun as a particle accelerator that smashes two electrons into each other at high speeds and charts their destructive impact. Particle number one is Bunta Sugawara, an iron-browed man of action born in 1933 who came of age during World War II and its aftermath and found fame playing a hard-bitten yakuza in Kinji Fukasaku’s epic five-part Yakuza Papers series (73-74). By the end of the Seventies, he was an iconic tough guy, not a hero but a survivor who’d do anything to win. He was also 46 years old, out of touch with Japan’s youth.

Particle number two is Kenji Sawada, a pop star born after World War II, and the only Japanese national ever to grace the cover of Rolling Stone. Dubbed “the Japanese David Bowie” by critic Stuart Galbraith, Sawada has sold 16 million albums to date. Barry Gibb of the Bee Gees wrote songs for Sawada’s original band, The Tigers, who starred in three feature films together à la The Beatles. By the time he appeared in The Man Who Stole the Sun, Sawada was headlining sold-out solo shows in which he’d cross-dress, stomp around on stage in a parachute, and spit whiskey at the audience. He was 31 years old, four years into an unhappy marriage, and full of piss and vinegar.

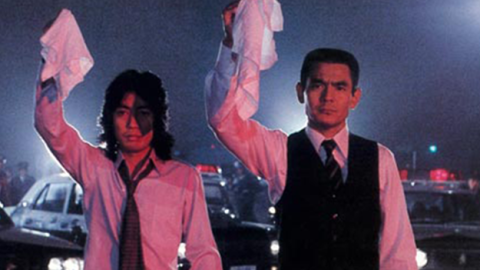

The Man Who Stole the Sun is all about what happens when these two icons clash. Not just the actors, but their characters, their genres, and their generations. Sawada plays Kido, a shambolic high-school science teacher, who smacks gum and naps in class when he’s not donning a gi and unleashing frenzied karate demonstrations. Sugawara is Inspector Yamashita, a tough cop who… well, he’s pretty tough, which is about all we know (or need to). The two first meet when a deranged WWII vet hijacks a busload of Kido’s students, makes them detour to the gates of the Imperial Palace at gunpoint, and demands an audience with the Emperor so he can learn how his son died during World War II. Yamashita and Kido wind up taking him down together, and exchange guarded, cross-generational mutual respect.

But Yamashita’s got a buzz cut and Kido’s got long hair, and never the twain shall meet. Also, Kido is building a nuclear bomb in his one-room apartment. After he steals fissionable material from a government facility—in a wildly experimental action scene utilizing flamethrowers, stop motion, and still frames—the movie slows down to spend almost 45 minutes of screen time on him building his bomb. (Some of the footage was cut at government request because the instructions on how to build the bomb were a little too detailed.)

Once Kido is armed and dangerous, he begins slowly going insane, like every nuclear nation on the planet has in one way or another after getting the bomb. At first his demands are minor, even goofy. He calls the cops and demands that baseball games running into extra innings no longer get their broadcast cut off precisely at 10 p.m. to make way for the local news. Then he insists that the Japanese government stage a Rolling Stones concert (Mick Jagger was in fact banned from Japan by the Foreign Minister for his drug convictions—the Stones didn’t play Japan until 1990). The demands are harmless, but they drive Yamashita bananas.

Power corrupts, and nuclear power corrupts absolutely. Soon, Kido gets more ruthless: he asks for half a billion yen (about $23 million in today’s money) and when Yamashita’s manhunt gets too close, he warns the police to stand down or he’ll detonate his bomb. By the end of the movie, like Gollum with his ring, Kido’s “Precious” has corrupted him completely. His bomb is the only thing that gives his life meaning anymore, and he’ll do anything to hold onto it, even when he’s run out of demands.

A straightforward plot description doesn’t do justice to this movie which veers all over the stylistic map, going from documentary realism, Seventies experimental filmmaking, and Saturday morning kiddie shows. Kido is a master of disguise, dressing up as an old man to steal a gun from a cop, and as a pregnant woman to plant a bomb in Japan’s Diet building, and he executes his disguises with all the glee of a five-year-old at a costume party. When the police finally find and take away his bomb, he smashes into their four-story building swinging on a rope and yodeling like Tarzan. Cars hurtle down the streets of Tokyo Hal Needham–style, cops drop hundreds of feet from helicopters only to start running the second they land, and Yamashita takes Terminator-levels of punishment without slowing down.

Shot mostly without permits (but with the two-fisted protection of right-wing nationalists), the movie sprints through the streets of Tokyo, weaving in and out of an actual Communist Party May Day march, staging elaborate games of cat and mouse through real crowds. Kiyoshi Kurosawa, whom Hasegawa hired as an assistant to the director, was even arrested for throwing fake money off the roof of a building and almost inciting a riot during filming. From these wild variations in tone, it may come as no surprise that Hasegawa studied under Shohei Imamura, who also trained Takashi Miike at his film school. There’s more than a little Miike in The Man Who Stole the Sun.

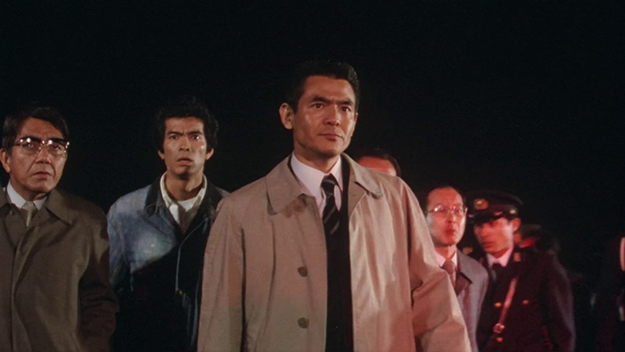

But every time the movie comes close to crossing the line into total absurdity, director Hasegawa pulls it back. Thanks to all the time he spends around his bomb, Kido begins to die of radiation poisoning, and even during some of the movie’s most ridiculous moments Hasegawa suddenly switches gears to linger on his bleeding gums and hair loss. But the radiation hasn’t just poisoned Kido’s body—it’s also poisoned his mind. When the film begins, Yamashita is a bullheaded establishmentarian bummer, raining on the creative parade of this Merry Prankster, but the longer Kido is around his bomb, the more its death urge infects him. By the film’s final reels, he has put plutonium in a pool and murdered dozens of children, and he’s planning on taking out all of Tokyo when he dies. His hippie antics have gone from the Summer of Love to the Summer of Sam in two-and-a-half hours. We start out wanting to see Yamashita take a pie in the face for his stoic seriousness. By the end, we’re begging for him to save our lives.

But that’s not to be. Hasegawa knows that we don’t like the guys who put on suits and punch clocks and enforce rules. Japan in 1979 didn’t want Yamashita anymore—they wanted celebrities, rebels, rule-breakers, and rock stars. Pop culture worships the people who will ultimately destroy us. In the final scene of The Man Who Stole the Sun, the consequences of this choice are clear. As a planet, we’ve chosen Kido over Yamashita. Now all we have left to do is die.

LINKS! LINKS! LINKS!

… Check out the trailer for The Man Who Stole the Sun but watch it with the understanding that it barely even hints at the celluloid mayhem hiding under the surface of this movie.

Director Kazuhiko Hasegawa only directed two movies, but he was an enormously influential producer in Japan. In this long interview he talks about his entire career, but it contains tons of gems regarding Man Who Stole the Sun. His description of the idea behind the movie as “So stupid, so good,” is right on the money, but it’s his comments about working with Leonard Schrader (Paul Schrader’s brother) on the screenplay that really score. When Schrader objected to showing Kido dying of radiation poisoning because it would make the movie too heavy, Hasegawa responded: “Asshole, how can a movie about a nuclear weapon NOT be heavy? It definitely should be super-heavy, and at the same time it needs to be super-hilarious and striking in a way never imagined!”

… China is regarded as a country where movies can make massive profits, and also as a country where those same massive profits can sometimes disappear down a rabbit hole that makes Hollywood accounting look honest. Finally, a director is going to court over it. Zhang Yimou is suing his producer and partner for the past 11 years, Zhang Weiping, for refusing to share $2.41 million in profits from A Noodle Story (09). Zhang Weiping says the money has already been paid, and anyways it’s too late to file a suit over that old movie. The two are in the middle of a bitter falling-out, and since there are foreign players involved (Hong Kong’s Edko Films), this case is being watched closely to see if it’ll shine a light on the Chinese film business’s sometimes shifty revenue distribution practices.

… Sanrio, the toy giant behind iconic characters with no mouths like Hello Kitty and Bad Batz Maru, have started a U.S. subsidiary to produce movies based on their trademarks. First up is Hello Kitty! The Super-Expensive Motion Picture (the tentative title which I just made up) which’ll be an animated film budgeted somewhere between $160 million and $240 million.

… One of China’s biggest retail companies, Alibaba, made big news recently when it launched its film and entertainment ventures. Wildly overvalued on China’s stock market (which is having its own problems right now) Alibaba immediately became a major player on the Chinese entertainment scene. But mo’ money means mo’ problems, and Patrick Liu, the head of Alibaba’s digital entertainment unit, was arrested over the weekend by Chinese authorities. Alibaba has been quick to say that this was in relation to his work at another company, but no one’s quite sure what’s going on right now.

… Donnie Yen is in the new Star Wars movie, screamed headlines last week! Tabloids went nuts! Websites lit up! Well, probably not. The rumor was traced back to Hong Kong’s notorious gossip rag, Apple Daily, which historically has had a tenuous grasp of the truth. They also stated that he’s flying to London later this month to start filming. Considering that the Star Wars sequel hasn’t even started filming yet, and won’t until later this year, this sounds a lot like a rumor and some wishful thinking. Still, it’s a great idea!

… Upcoming Blu-ray and DVD releases of note include Gangs of Wasseypur, Anurag Kashyap’s massive Indian gangster epic, Donnie Yen’s over-the-top (and fun!) martial arts movie, Kung Fu Killer, and a massive collection of the complete Stray Cat Rock movies from Japan in a sweet set from Arrow Films.

… On July 17, the biggest Korean movie of the year so far, Northern Limit Line, will hit American screens in New York, New Jersey, L.A., Chicago, Dallas, Seattle, and more. Even Canada gets some screenings!

… Also coming to U.S. theaters soon is Korean action maestro Ryoo Seung-wan’s latest movie, Veteran. You can go here for a synopsis and a trailer.