Interview: Tom Skerritt

Alan Clay, the protagonist of A Hologram for the King, gets afflicted with middle-age flop sweat in Saudi Arabia, where he attempts to sell King Abdullah a holographic communications system. Forty years ago the role would have gone to Jack Lemmon as he sadly evolved from comic genius to specialist in bourgeois angst. Now it’s a natural for Tom Hanks in his “I am middle-class America” mode.

It’s the salesman’s gnarly dad who’s the charmer and scene-stealer. In both Dave Eggers’s 2012 novel and Tom Tykwer’s film version, he delivers one dynamite speech (here’s the book’s version): “I’m watching this thing about how a gigantic new bridge in Oakland, California is being made in China. Can you imagine? Now they’re making our goddamn bridges, Alan. I got to say I saw everything else coming. When they closed down Stride Rite, I saw it coming. When you start shopping out the bikes over there in Taiwan, I saw it coming. I saw the rest of it coming—toys, electronics, furniture. Makes sense if you’re some shitass bloodthirsty executive hell-bent on hollowing out the economy for his own gain. All that makes sense. Nature of the beast. But the bridges I did not see coming. By God, we’re having other people make our bridges! And now you’re in Saudi Arabia, selling a hologram to the pharaohs. That takes the cake!”

Who could put that speech over better than Tom Skerritt? He’s got a weathered, expressive sort of all-American look as well as the rolling yet emphatic vocal patterns of a man who, once he gets going, likes talking—especially talking shop. He knows how to imbue a populist complaint with ornery wit. Industrious as ever at 82, he’s been an emblematic and exemplary American actor for five and a half decades. He stands for genuine, broad experience in an increasingly specialized and digital culture.

I spoke to Skerritt over a year ago. He’d shot his two scenes for A Hologram for the King a year before, and he’d just finished playing a devout, reclusive 91-year-old in a small independent film called Day of Days. He had the passion and recall to evoke several pop culture eras without pausing for a breath. He vividly recounted being present at the birth of the Hollywood Renaissance, acting in M*A*S*H and Thieves Like Us for Robert Altman and doing a bit part in Harold and Maude for Hal Ashby. He also recollected front-line memories of American TV: acting in Westerns like Laramie and war series like Combat (for Altman); starring as Sheriff Jimmy Brock in David E. Kelley’s Picket Fences (92-96); doing guest shots on The Good Wife and Madam Secretary.

On the phone from Seattle, he was quick to tell me that he’s even busier when he isn’t acting.

A Hologram for the King

You’ve done a number of TV shows and movies in a row. Are you taking some down time now?

I’m a writer and a teacher, so that’s more active than what you’re talking about. The work that comes along is often a respite from the intensity of what I’m usually doing in life. I have a Midwestern work ethic actually.

I won’t go on too long about my background. Being a blue-collar middle-class guy from Detroit, I had transferred out to UCLA as an English major who was interested in directing. I had done a little theater as an actor, only to overcome being shy and self-conscious, and never intended or thought I could make a living as an actor. I thought I would continue writing and continue acting if I was going to be a director. I happened to be seen as an actor and I was hired for a little low-budget film and I thought, hey this is a great way to learn how to be a director, to be a participant in the actual reality of making a film. You can’t be a filmmaker purely by going to the university, as you know. The practical knowledge, the street knowledge you can gain by being on a set, being around that, being around the way people talk, the way they approach the business, was really the benefit I saw in it from the beginning.

So from the beginning I was basically a story guy. To me film was always about putting together a series of frames and making them rich and full, because there’s always the subliminal subconscious excursion going on, that you have in going forth to do a film. It was about the things you don’t fully realize you’re experiencing, those wonderful little things that go on around in the background of a film like M*A*S*H. When I did this little $1.98 film that I was hired to do when I was still at UCLA [War Hunt], I happened to work with two other actors named Robert Redford and Sydney Pollack. And then I met a television director who lived near me, in Westwood, who was Robert Altman. I was mentoring with Robert Altman as a filmmaker when M*A*S*H came up. So my whole approach in the business has been quite different from most actors. I got lucky. So it wasn’t a planned device. The more I wanted to work as an actor the more I wanted to direct.

I was learning more as an actor about what to do and what not to do. Altman—I was basically spoiled by him and by another director, Hal Ashby. You may be aware of him. I mentored with both those two guys over a three-year period: preproduction, production, and postproduction, so my thinking is about a little more than just acting in a movie. I’ve been writing ever since. And because Seattle has one of the most enthusiastic film communities in the country and has more young people shooting films than anywhere else, and those films are often never fully realized because they are not tending the garden of storytelling, I started a school to teach how to tell a story. That school’s now 11 years old. It just tells about how to tell a story; this is not about going to Hollywood. If you tell a story well, from that place which you know the best, which is your life, your experiences, it has a better chance of being fully realized as a film—or as a book, for that matter. That’s what I’ve been busy doing. And part of that school has gone down to Fort Lewis to teach PTSD vets who are transitioning from active duty to civilian life how to tell a story as well.

As you know, as a writer, it’s great therapy just to write, to express yourself. I had been up to Crested Butte, Colorado, which is a ski area, about seven years ago, and the Iraq thing was going on, which I was having big issues with, and I went to dinner with twelve PTSD-affected soldiers, very severely emotionally and physically damaged. I was haunted by that, their looks of terror and anxiety and surveillance, always in this lovely surrounding of good food and nice people. They were conscious of any noise. And the looks and that experience with them stayed with me. I started seeing the degree to which PTSD was being recognized finally. And the military was not prepared to actually deal with PTSD, so we came to have numbers of 22 a day committing suicide. I had the alumni of my class write assessments, and virtually all of them said that this three-week intensive learning experience changed their lives. So I redesigned the program and got a group of three teachers to go down to Fort Lewis, to teach the active soldiers transitioning into civilian life how to tell a story. You know, you’ve got to be honest to yourself when you’re writing, and try to always communicate it the best you can, in what you write, what you want to say, and how you want to say it.

The $1.98 film—are we talking War Hunt, or was there something I missed before that?

War Hunt, I’d forgotten the name of it, War Hunt with Redford and Sydney Pollack. I had never worked professionally at all, I just had done theater in college, so I really didn’t know what I was doing, because when you’re doing theater, you have to have a pronounced physicality [laughing]—you’ve got to broadcast, you know? And you can’t do that on film. And I remember going through that process of learning how just to be, you know, a film actor, quite different than a stage actor.

War Hunt is about the damage of war…

I didn’t have an agent or anything. I was in my last semester at UCLA, and I thought the work I had to do with actors had to be done with actors who were better than I was. I thought I had to do theater outside of UCLA, because doing academic theater is more about getting a good grade. It wasn’t as demanding as going out and working with professional actors, people who were making a living as actors. I happened to be doing community theater, for want of a better way of expressing it. I forgot what play it was but the Sanders Brothers happened to see me in that play and asked me to be in that film, that’s all. Just a matter of circumstances…

War Hunt

Before that: you came from Detroit, and went to Wayne State?

Yeah, I came out of the service, and went right to Wayne State. I was in the Air Force. There were four or five of us who were having a few beers one night—we must have been 17, just got out of high school—we didn’t know what we were going to do, we were not ready to go to college. We just had a couple of beers, and thought, “We want to travel, we don’t have any money, and we want to get away from here.” And we enlisted the following day, four of us, I think, enlisted at the same time. It was a four-year term.

So you wanted to see the world? How did that work out for you?

Well, that’s what I thought would happen. I wound up being the kind of guy—a classifications specialist—stationed out at Austin at the time. Some order would come in for a mechanic to go to Greece—a specialization of some kind, or an auto mechanic to go to some wonderful, exotic place that I wish I would go to—and I was the guy who would have to make the selection on who was the most eligible and required to go to fill those positions.

Did you spend most of the time in Austin?

Reno, Nevada, and a little bit in East Saint Louis, Scott Air Base, I think it was, and mostly in Texas at what is now the Austin airport, used to be Bergstrom Field. I had hoped to do some flying when I got into the Air Force, but I didn’t really have the math I needed to get to be a pilot. But they did have some small single-engine piston Piper Cubs that were available for you to take, and a flying club, so you could learn to fly, and I did a little bit of that…

You seem at ease in Western landscapes.

You’ve been out in the desert, haven’t you? You know how it feels. It feels like Western history every time you go out in those places. It’s very relaxing…

So you did the Air Force and you went back to Wayne State and Detroit, and is that when you began to think about being an English major, writing, things like that?

I started as an English major, I had done some writing and had also done some artwork and was studying art at night, not at Wayne State but at an art school, close by… I really didn’t know at that point. Very few of us know at the point what we’re going to do in our lifetime, at 20-21. So I thought English, Geology possibly, and they said because I was basically very self-conscious and shy, that I had an opportunity to be in a play, and this would be a great way of overcoming that, and that’s how the acting happened. It wasn’t something I was pursuing in the way it ultimately rolled out.

People were saying you’re pretty good, you ought to go to New York, and I was thinking about whether I wanted to be an artist, because I was a pretty good artist. And I had a college professor in English who said, “You’re a writer, you ought to be a writer,” so I’m having all of this stuff going on but I knew I didn’t want to live in the four seasons we had in Detroit, where the winters cut through you like a knife, and the summers were like a damp, warm blanket that didn’t cool off at night, and I’d been to California in the service so that’s where I wanted to go. And I thought I’d go to UCLA because I was interested in directing. There was something about the totality of visual storytelling that really appealed to me. I went out there as an English major after one year at Wayne State. Film directing really appealed to me. I directed a couple of plays back in the theater at Wayne State, original plays that someone else had written, and it appealed to me. I thought I’d take that to film, because that included the art classes I was taking at night—it was the convergence of a lot of things in my life. So when you ask about the acting, it doesn’t stand alone in my life, it’s what I made a living doing, and I’ve been very fortunate to do so, but it’s the whole thing, the storytelling-in-film aspect of it is what I found appealing.

Was it The Rainmaker that got you recognized? It’s sort of a show-off part.

Yes, it must have been The Rainmaker, I was doing that, when the Sanders Brothers came and saw it one night and asked me to be in their film War Hunt. I had no idea what the hell I was doing in front of the camera, I mish-mashed everything, I had no idea about any of that. We all go back to that. Sydney Pollack was just one of the other actors I was really impressed with and Redford was a new guy who had been working in film and television and theater prior to that. So he was sort of on his way up; he was kind of the hot new guy, at least that’s how I saw him at the time… Sydney only talked about directing; it’s really what he wanted to do, he never talked about teaching. Directing was what he wanted to do then. And that’s where their relationship started. And that’s where my long relationship with Redford started.

Redford was living up in Laurel Canyon; I had more of a relationship with him than I did with Pollack. And Altman lived near me in Westwood. I was actually in Brentwood. You know where the VA district is, where the graveyard is? I was just west of that so I could walk through the VA area over to UCLA in Westwood. Altman lived around there somewhere; it’s a long time ago. I know I met him down there somewhere somehow. I hadn’t done anything other than War Hunt. I had just thought, there’s nothing to this, I didn’t even have an agent and I’m being hired—Oh god, that’s great! I just thought I’d learn all I can until I become a director. I just ran into Altman; I don’t remember the specifics. “I’ve seen a few little clips of this film [War Hunt],” he said one day, “Why don’t you come over and do this little thing in this Combat! thing I direct?” I thought, “Sure.” That’s how those two things came up. It wasn’t any hard, thought-out looking for an agent. It was just good luck. Really good luck.

You had four years in the Air Force. The pressure on people now is to start out as an actor and make it as an actor. Aren’t you a believer in experience? Having other ambitions, interests, experiences before you go into it?

I can’t tell you how much I believe in that. I paid my dues in other ways. Life and death situations; a diversity of experiences in my life. And all of that is what I bring to the work, hopefully. Today I think I stretch it more in the writing and very much so in the teaching of how to basically… I have some good teachers up here who teach a variety of things—building a character, story-building, so on and so forth, and what I teach specifically is that those who want to write should get on their feet and act and direct one another’s work. Everybody has to write a scene and then go off and give that script over to some of the other students and they would direct and act in it and the writer would have to go and do someone else’s play. You can’t be involved in your own play. So they get to see what it looks like objectively, to see it mounted, and as a writer they learn to go through that threshold of reserve that we have about getting into acting, or how to put it together as a director.

So I just have always felt that as an actor, right off the bat, doing writing, directing, all of that, and learning editing, at UCLA, with all of that observation I could bring more diverse experience to the work and less of an ego. If acting is all you ever want to do—or directing, or writing—and that’s what you do, this is not a fault, necessarily, but it’s so singular in its focus that it excludes all those things that cause longevity, that bring more than just you protecting yourself as an actor and being a pain in the ass. You have more understanding of what the director is going for and also how to interpret the writing better. I mean, common sense just dictates you’re going to be a better director, actor or writer, if you know what the others are by experiencing them. How do you know what ‘hot’ is unless you touch it? It’s a simple as that. It’s what I always thought from the beginning. For a long time I kept resisting acting as a profession, though I was getting more and more work, because I really wanted to direct. Finally I had a family, I had to feed them, and fortunately I was able to make a living as an actor.

Doing TV—The Virginian, Alfred Hitchcock, Laramie—were you “go in and get the paycheck,” or was there also a sense of learning your craft and getting confidence. Was it another school, those seven or eight years of TV work?

It’s all an open book. Every day you walk out and learn something new. Now, at this time in my life, I find life so exciting because there’s so much I don’t know. And I’ve always thought that way. And everything I did, particularly with guys like Altman, or Ashby, or some of the other guys I’ve worked with, later on with Ridley and Tony Scott, I’d follow them around, even when I wasn’t working, just to see how they set up shots—particularly Alien, I was all over the place, I mentored with Ridley Scott and with Tony, [on Top Gun] for that matter, they both sensed that I wanted to know what they did, how they did it, why they were doing it, and I learned a lot from them. A lot. By being open to being the student, a film student, who was working as an actor on the film. And they appreciated, Altman certainly did, my God I learned a lot for him.

In Day of Days you’re playing 10 years older than you are, at least according to the notes here, 91, and in M*A*S*H, you were such a youthful character, but you were probably ten years older in real life than the character you were playing on screen.

M*A*S*H. Keep in mind I’d been mentoring with Altman a few years prior to that, so I knew what he was capable of. He was the first director I’d met who made me think. I hadn’t worked in television, so right after War Hunt I did a day or two in Combat!. Mainly because he asked me to and I was interested in learning from him. Here was this TV director who was making something available and he loves to teach and I love to listen. I was already mentoring with him, so I went in with that idea and then mentored with him whenever I was able to on anything else he was doing. I would go over to his office in Westwood and just listen to him and watch dailies, and he’d explain why he shot something a certain way and all this kind of thing. And I hadn’t seen him for a couple of years, and I was writing something, and he was always good with feedback on writing. And I called him up to talk to him about this thing I was writing, and he got on the phone [laughs], I’ll never forget it, and he says, “Skerritt—God, yeah, yeah, yeah-yeah—Um, ah, listen, let me call you back tomorrow.” That was it. Next day I was in M*A*S*H. I had jogged his memory—I hadn’t seen him for a couple of years, and he was going through casting. That’s how that happened.

In M*A*S*H, you’re actually a constant presence from the beginning and really crucial to a lot of the action, including all the stuff with Hot Lips, but you don’t say as much as Gould and Sutherland do to explain themselves. Your character has some Southern prejudices, as I recall, that you cheerfully overcome. You sum up the rebelliousness and competence more in your attitude, infectious and breezy. Was that what you and Altman were going after?

Oh man, we don’t go after things, we just have them. This whole creative process, research and all of that—I had done enough background in television, mentoring with Altman and a couple of other television directors I knew prior to M*A*S*H… I knew I could just trust my instincts, even though consciously I’m doubting it all the time, subconsciously I obviously was in tune to what I was going to do instinctively. I realized very early on we’re simply the product of all our experiences, so allow the good and bad of it all—hopefully you live through the worst of it—to inform your instincts which are going to drive your impulses, which is acting or painting or looking through the camera at a shot you know is extraordinary and you’re the only one seeing it, so capture it to share it with other people. The creative process is trying to capture something you’ve experienced and that you’re putting together and that you want to communicate and share with other people. No secret to that.

But as far as M*A*S*H is concerned, I was really quickly onto what he was doing. Prior to shooting, he cast the background for example. They weren’t just extras—these extras were schooled improvisational actors that he got from San Francisco and Los Angeles, these people who knew how to function in a loose situation, that he intended to set up with that material. It was very clear to me early on that this was going to be us, 80 percent improvisational, we looked at the script and got some ideas. It was a solid script, not a great script. And the improvisational skills that I had were tempered by the discipline of what you must do as an actor, and that’s what you do instinctively—you don’t analyze it, you just are. If you analyze it, you can’t do it. You know how it is, you just gotta throw it out there sometimes. I took a lot of risks with that, and sort of knew that Altman would get rid of the worst of it or just scold me. I loved working with that guy, because we knew each other well enough, he could just say, “Skerritt, that’s such bullshit, what did you do this for, why’d you catch that football?” “Because it was coming my way, man!” [Laughter] “Yeah, but I got to shoot it again now so Sutherland can catch it…”

M*A*S*H

Next time up with him was Thieves Like Us, and I guess a guy like Altman could see you had the capacity for these two almost opposite parts. You went from the happy-go-lucky, super-competent guy in M*A*S*H, to this bitter, drunken guy in Thieves Like Us. It must be a gift for an actor to have a director see your range.

It’s interesting you say that. I had done several things, different things with him in television prior to M*A*S*H, as I mentioned, and they were all Southern guys. I think when he was doing post-production, I was watching how he was cutting Thieves Like Us together, as I did a little bit with M*A*S*H. and I asked him, “How come you always cast me as a Southern guy? And he says, “Because that’s how I see you.” [Laughter] So that’s it! So that’s about as deep as it goes!

Oh, man…

Yeah, we’d just yell at each other a little bit. He didn’t like this whole movie star stuff and I don’t particularly like it either. I don’t know what it is. People call me, “You’re a movie star, ain’t ya?” but I’m an actor who works in film. That’s it. The rest of that stuff is what other people label it. That’s why he and I got along. He knew I was a student of film, number one, and I still am.

Was he a student of film?

That never came up in conversation.

Your family in The Turning Point was the best thing in that Herbert Ross movie.

I hadn’t worked with anyone of that sort of disciplined background. Ross was in ballet and these guys can be—I don’t know if you’ve been around ballet—particular, since we’re talking about ballet. Ballet can be a difficult profession. Young people come in and take a lot of abuse. Teachers saying, “Oh, you’re terrible, you stunk, you plop your feet on there like you’re hitting a big slab of ham against the floor… What are you? Ham-foot…” They can get really insulting to these dancers, the things that come out of these instructors’ mouths. Deep! They just coerce the dancers into being perfectionists, and those that can’t make it are just crushed. But in Turning Point, I was dealing with an ex-dancer and an ex-teacher and a teacher-choreographer, that’s what Herb was, and I got along very well with him, but he could be not an easy personality. So I learned some discipline from him, some acting discipline. And working with Anne Bancroft, Shirley MacLaine—you work with broads like that, you gotta shape up. I learned—I moved some corners on my skills by working with Herb. I did two films with him. I did Steel Magnolias.

To be honest, before this I didn’t realize how big your focus was. You know, I don’t always think of Ridley or Tony Scott as actor’s directors, but you obviously got very excited working for Ridley.

I found out very early on a lot of it’s really up to you, not up to the guy who’s hired to direct it. In television, with very few exceptions, you rarely have a director who’s directing you as an actor, they’re really hoping to get the shot and move on to the next scene—at least that’s how it was in the ’60s and ’70s. Now there are better shows where the directors are more skilled in terms of knowing how to deal with actors. A lot about directing actors… First as an actor, you’ve got to bring your own skills in there. And you put them out there, and a good director will say, “That’s not going to work, back up on that other thing where you used your left hand instead of your right hand, because it looks better, because it’s closer to the camera,” or whatever it is. They give you a couple of things about what they noticed in your performance, in terms of an action.

Now there’s more of that in good cable shows and really good shows like Madam Secretary and The Good Wife. There are good theater directors and theater actors doing those. You’re working really on a good level with those situations. Those are more exciting because you’re working more with actors you respect and directors you respect. In the old days, when I was coming up, you’d just learn all this stuff. I’ve seen where directors are looking at the script, just making sure you did it word for word, the guy would look at the cinematographer—one guy in particular never looked at the performance, just hearing the words—then ask the cinematographer, “You got it?” “Yeah.” On to the next set. I never forgot it. And that was before we had the video playback and all that.

But I had Altman and then I had Ashby—Hal and I got to be very close in the early ’70s. I had met Hal right after M*A*S*H, through Beau Bridges, who did Landlord with him. And we got pretty close, and I used to go watch him cut film, every day, because you learn more about storytelling watching a good editor, and Hal was an Academy Award-winning editor, and such a terrific guy. And spending time with him and the humor and the joy of doing what he did, being around that, along with what I had picked up from Altman, the two of them…. I had this gift for over a three-four year period, from ’69 to ’73, I’m going between them—he’s in preproduction, the other one is in postproduction. He’s doing something I can go over for a few days and watch how he works with actors in production. I was doing a lot of that. What happened with Harold and Maude, he got the script one day, and I’m over at his office, I spent a lot of time in his office, up on Appian Way and the house he had up there at the time. And he got this script, which I looked at, and I said, this is terrific. This graduate from UCLA, he wrote this thing called Harold and Maude; Hal said this thing was way ahead of its time. I remember this day I came over and he had just gotten the job and one of the first people he talked to was Elton John [briefly trills “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road”]—he was talking to him about possibly being Harold. And I remember after Elton left the room, I was in another room, saw him leave—Hal came by and said they’d had a nice time, a lot of laughs, and all that, and he looked at me and said, “He’s too English.” And I had worked with Bud Cort in M*A*S*H and I threw that out to him. And Hal was doing Harold and Maude and I was on the phone with him almost every night to see how it was going. And one day he said the motorcycle cop drove out of the shot, and he didn’t put the kickstand up all the way, and it triggered just out of the shot, and it threw him off, and he broke his leg, and Hal was very upset about the poor guy breaking his leg. Understandably. And it gave me an excuse to go up there; I paid my way up there, to be mentored again and see how he shoots.

That’s how I became part of that one. And at the end of it, we’re finished shooting, and we’re in Hal’s office and the producer’s there—Charley Mulvehill, nice guy too, liked him, don’t know if he’s still around, haven’t seen him in years—he says, do you want to take credit for this? I said oh, let’s not bother about doing credit, I just came up to spend some time with you guys. Then I said, “Wait a minute”—we did silly things in those days, and we still do—and I said, “You know, Martin Bormann, second in command to Hitler, nobody ever found out what happened to that guy. Everyone else they were able to trace, but that guy just vanished.” I said, “You know, I think he went to Oakland and became a motorcycle cop.” So he gave me billing as Martin Bormann. Just fun. Don’t take it all too seriously, just do this stuff. It’s how we make a living. Shit, man, you have to enjoy life, we’re here and we’re gone. Find the best ways and most intelligent ways to enjoy it without killing yourself. “Take the risk of possibility,” that’s what I love to say.

Alien

As for Alien—what stands out for me is that the ensemble is so hardcore. Weaver was new but she was theater-trained, Harry Dean Stanton, Yaphet Kotto, all those guys. And you were the captain—was being skipper to that bunch part of the fun?

Little history on that. It panned out that I was the first one they came to, because I was doing another film and they gave me the script; they said they didn’t have a director, no one is cast yet, and it’s going to be done for $2 million. And I read the script and frankly I just thought, everything’s unknown, and it’s going to be $2 million budget, and it didn’t appeal to me as an actor because there wasn’t much acting challenge per se. But it was a nice solid screenplay. $2 million and I don’t know who the director is. To do that for $2 million bucks it would have to be Ed Wood directing it. That didn’t appeal to me and I passed on it. Meanwhile, I’d seen The Duellists, which was Ridley’s first film, and I thought, Whoahhh… I mean, I’m a great appreciator of art, I studied to be an artist, so I know an artist when I see it. So then a producer calls up and says we have a $10 million budget, 12 million, something like that, and Ridley Scott is going to be directing it… and I say, “Hold on.” And that’s how that came about.

So much of this stuff is based on the directors, they’re so much part of the selection process. You look at a piece of material like that, see it one way at $2 million and you don’t know who the director is, and you see that this could not be an overly exciting challenge to do as an actor, and I don’t know the rest of it because I don’t know who’s going to be involved, and I was very active at that time and getting a lot of offers, and it just didn’t strike me. But having seen The Duellists and seeing what I’d be working with and the level I’d be working with, that’s… And then the actors that they had. I just felt so flattered to be with all those actors and with this director. This piece of writing I’ve got in front of me and working with these actors, I’m blessed. It’s me that’s getting everything out of it.

How did Up in Smoke come about?

Same deal. I knew Lou Lombardo, who was the producer, and Lou Adler, who was the director, I only knew him slightly. As I recall, in Westwood I ran into them, and they were talking about doing this picture next week with Cheech and Chong. They said, “Why don’t you fall by and do this thing?” I thought, OK. It’s the same deal as Harold and Maude, I thought, “Yeah, what the hell, I’ll go by there.” I had a lot of fun doing it, but what I brought away most significantly from doing that was, one day Cheech and I were out just looking up at the sun and enjoying that wonderful weather of Southern California at the time. And I said, “What a wonderful way to make a living.” And he said, “Yeah, man, it sure beats roofing for a living.” So that’s my stock line. “It sure beats roofing for a living.” You see the things you pick up that are really important? This is the stuff that’s really important that you take away from the work.

What about your friendship with Redford?

We were friends through the ’60s; we both had families, so we didn’t see each other a lot, it wasn’t like we were hanging out. He was making a living and becoming Robert Redford. But he’d tell me about his dream and we’d talk about it. We both had this view of Hollywood as something you had to keep on guard about this, don’t take this stuff too seriously. And we had a respect for independent filmmaking—we both had that and talked about it a lot. One day he’d gone with his then-wife Lola and her family lived in Provo, Utah. They went to visit and took a drive up this canyon in the mountains there, and saw this area where this farmer had this whole big canyon for sale—he was going to sell out the cows’ run and all that. He had inherited some money I recall from an aunt, or whoever it was, and had some extra cash, and he said “I just really bought this area and I wonder if some day I could have this as a place where independent filmmakers, good young talented people, could come in and learn about the business in a way they could not do in Hollywood.” Hollywood was not an open place for new people then, and certainly is not now. But the hope was that they could come and learn without the pressure of being really good right off the bat, learn the process, and have a whole kind of nice personal experience about themselves in film and how to go about this and some day had a vague idea of building a school up there, which became the Sundance Institute. And then he had students coming out of there but he couldn’t display the work that was pretty good, because the studios had their own distribution system and you were pretty much excluded unless you had an Academy Award film worth distributing. So that prompted him to start some kind of film festival up there, just to display the independent films that were coming out of Sundance Institute. That’s all. He wanted to keep it apart from Hollywood. So that’s how I recall that all evolved, some dream he had one day of building this school. I don’t think he ever intended it to be as successful as it became. The film festival became everything he hated about Hollywood; today, he’s sort of dissociated himself from the film festival because the ideal of independent filmmakers getting their wares shown—it sort of disappeared there because it’s become a market, full of those people in Hollywood he never could relate to.

Redford’s A River Runs Through It… Had you guys been talking of working again?

Back in the ’70s, we were just too busy doing other stuff and didn’t see each other much. I had signed to do a film with Ellen Burstyn up in Canada; I had done some rehearsals and came home. The day after I got back, or soon after I got back from Toronto, before I was to start shooting that film, he called one day and said “I’m going to have a script sent over to you, we could work together on this,” which was Ordinary People. And I loved the script, I said don’t change a thing, because he had been struggling off and on with that for four or five years, trying to get the script right. Finally he had Alvin Sargent do the one he responded to. He’s a very good storyteller, Redford is. Certainly was at that time. Jesus, I said, I signed to do this thing with Ellen Burstyn up in Canada [Allan King’s Silence of the North]. I probably could have gotten out of that to do Ordinary People, but I just felt morally obligated to do this other thing. So Donald Sutherland played that role. Otherwise, we just periodically would be in touch, and that’s how River Runs Through It came up. Read that and just had to do that.

I never had been [a fly fisherman]. Brad Pitt was sort of in the same status Redford was when I did War Hunt. We used to have some nice talks. He’s a good guy, a really good guy. You know, I’d tell him, you’re going to be doing some big stuff in years to come—don’t take it too seriously. Fully appreciate your talent and the gift that you have and it’s going to wear well for a long time if you don’t take it too seriously. He listened to that stuff and away he went.

Picket Fences

For a very big audience, you’re the guy who anchored Picket Fences.

I didn’t think I wanted to do a television series then. But I read the thing and I thought, whoa, this is different and then Kathy Baker was going to do it, whose work I really love, and I met with David [E. Kelley] and Kathy, and we all agreed we had to work at top level. I got to confess I’m kind of corny about this. I came out of UCLA film school. I thought film is one of the most if not the most influential of all media. We have a responsibility to work at optimum. We owe those people out there we’re doing this work for the best work we can do. I never lost that.

We’re going to be doing this series, and we all agreed to work at top level and are pushing it all the time to be better, and that’s the way we worked for four, four and a half, five years, for all it was. We worked at that level. The last year, David was not able to do it, so some other guy did it, and it wasn’t at that level that we were used to working at, so Kathy and I just felt, I don’t know, this is not the same. I directed four or five of those shows. I found the guy, don’t remember who he was, he was a little difficult, a little testy about me coming in and asking for certain things. David was always open to it. If I had a thought about a scene we were going to do tomorrow or in a couple of days, David would just sit and listen quietly, you never knew what he was thinking, and I’d finish and he’d say “Thanks,” and then he’d leave. And he’d come out with a script not just responding to my suggestions, but going beyond, what I suggested just triggered something for him to do even better, and I got better material every time. David gave us a rewrite—not that we needed it too often, not at that show, he was so brilliant. It was like I was working with Mozart, who never corrected a note in anything he ever wrote. It was just extraordinary to be working at that level, so three years or so later, when that other chap came in, he didn’t have those chops. We just felt we didn’t know if we cared to continue working this hard. We’d work at night to correct things that needed to be corrected; 16 -18 hours day we’d be putting in. Kind of tough.

It was wonderful satire, though I don’t know if it was always seen as that. But it has to be when you have the Pope arriving in this country but he hears of this little town called Rome and he decides to go down and say hello and he’s a witness to a murder. Then as a material witness he has to testify on the stand and have this Jewish attorney question him about the ideology of the Catholic Church and its oppressive history. [Laughter] That was David’s own thing about the Catholic Church. It was wonderful to work at that level. Don Cheadle was our third or fourth D.A.

It was the previous TV golden age…

It was class… Pretty impressive. In three years we had 16 Emmys, two for best show of the year.

What about your directing ambitions?

I had directed some theater and some Canadian half hour television show, couple of those I did… Also did a long-form two-day shoot for a cable network, also acted in it, which was hard to do. Most I’ve done for any one series was four or five, on Picket Fences, and for Chicago Hope. I was heading in that direction to direct television series, but I really did not want to be a TV director, I wanted to do features, and that really pushed me back into writing more, trying to write something of my own to direct, and I kept getting acting jobs. I’ve only recently been able to finish screenplays that I started writing 20 years ago, because of the time factor, family requirements, that sort of thing.

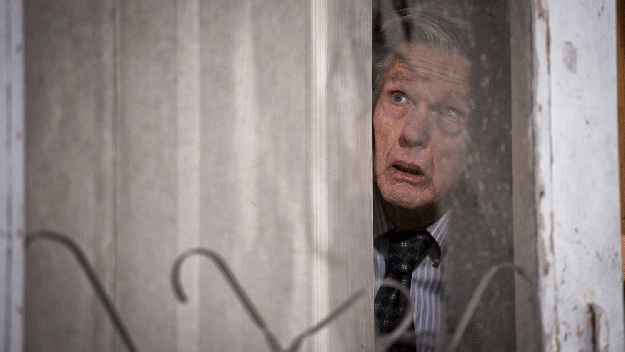

How did A Hologram for the King come up?

Like Seth [MacFarlane] with Ted, the director calls up and asks if I would do this thing, and I say, of course! . . . Lovely guy, Tom Tykwer, really a nice man. That was a year ago.

Day of Days

And what about Day of Days?

Came up in January when I was rehearsing with the Pacific Northwest Ballet, Don Quixote, up here. I had done Don Quixote first three years ago, with Pacific Northwest; it’s a great experience. I’m not a dancer. And I didn’t have any words to do. I’m just bumbling around there, being myself, charging windmills with my lance. Going in and out of sanity and insanity.

It was right after doing that ballet up here, that I was down in Anaheim, with [writer-director] Kim Bass, talking about Day of Days. Real nice script. Kind of like My Dinner With Andre, remember that one? That kind of thing. Just a guy who wakes up in the morning, and sees the light from above, and he assumes that’s telling him, “Oh boy, I’m dying today.” So he dresses up, shaves, all that stuff, sits there and waits to be taken. Looks out the window, see if it’s coming that way. He lives alone in a small, little modest house. And his social-services caregiver arrives. She’s a stranger. He’s used to this one who’s come every day for the last three years to take care of him, and this particular day that one’s ill so they send over a substitute, and they get into this argument, religious and otherwise, over his saying he’s going to die. She says that’s outrageous, how can you know you’re going to die, you just die. And there’s this religious war in the argument and it gets into belief and disbelief and finally she gets pissed and is ready to leave, and I apologize. They talk about the past and get to know each other and they become very dear friends by the end of the day. And it’s just that kind of a nice, sweet piece. No guns, no crashes, no explosions.

A lot of this is really how whatever you’re doing is going to affect an audience. And this has a lot of humanity in it, so that’s very appealing. One man’s struggling with his own life and death and the regrets that everyone has. So you get a character study that anyone can relate to, and I think that’s valuable. See how it turns out! Kim Bass is a good guy, wrote a good script from what he knew, some background in it, some reality and truth that he himself had experienced, but he’d have to tell you about. Once they’re done, I have nothing to do with them other than when they’re finished, you do some promotion if you’re available. I don’t just stay with the film.

And what’s the name of your school?

The Film School. It’s housed in the Seattle International Film Festival office. We just got busy teaching. We were going to change the name, but we got busy so it’s still The Film School.