Interview: Sylvia Chang

From the broad slapstick of Aces Go Places (1982) to the charged family dynamics of Love Education (2017), from classic martial-arts adventures like Legend of the Mountain (1979) to the contemporary 3-D musical Office (2015), Sylvia Chang has been a key figure in East Asian film since her debut in 1973’s The Flying Tiger. A performer, writer, and director, Chang is the subject of a 15-film retrospective at Metrograph starting May 18. In addition to titles directed by King Hu, Tsui Hark, Johnnie To, Stanley Kwan, and Jia Zhangke, the series showcases five features she directed, including her latest, Love Education, and she will appear in person. Chang spoke about her career by phone from Kuala Lumpur prior to arriving in New York.

All About Ah-Long

Can you talk about how you broke into films?

I was singing on television and somebody spotted me and asked me if I was interested in doing films. I was very young, about 18. I just said, okay, let’s give it a try. That’s how I got in. Accidentally. I was very much on my own, I didn’t have a manager or agent.

The series includes several of your important early titles, like the Shaw Brothers’ The Dream of the Red Chamber [1977], where you played opposite Brigitte Lin, and Legend of the Mountain, directed by King Hu.

King was actually very much like a family friend. He was friends with my mom and with my grandfather, and also a very close friend to my first husband. He knew me when I was very young. So when he asked me whether I would do the film with him, I really felt very honored. We went to Korea for a year to do the film.

I will not say he was difficult, but he was making two films at the same time [Raining in the Mountain was the second]. He was very strict, he would not tolerate anything that wasn’t what he wanted. We had to be patient, no matter what the climate was, or what the problem with props was. He knew exactly what he wanted and he would not compromise. That’s why it took so long.

But he was not very difficult on the set because he allowed us to do the acting, he allowed us to give, and he accepted what he felt comfortable with. I liked the way King treated characters because he wanted us to be more human than opera singers. He didn’t want us to do any stage steps or anything that’s connected with how everybody thought these characters would traditionally perform.

You also worked with Tsui Hark: his film Shanghai Blues [1984] changed the way the Hong Kong film industry operated.

That was the first film from Tsui Hark’s company, Film Workshop. It was very tough working on it. I even got into a fight with Tsui Hark after shooting about how he treated the romance in the story. We shot many, many romantic sequences with me and Kenny Bee. When I saw the finished film, he had cut out all these nice scenes. I got really mad, and we didn’t talk to each other for a few years after that.

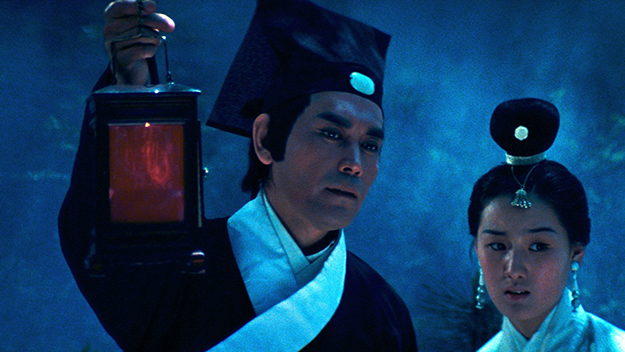

Legend of the Mountain

Did you always intend to write and direct?

My second film [The Tattooed Dragon, 1973] was with Golden Harvest, where I signed a five-year contract. It didn’t work out very well, but during that time I was very interested in everything that happened behind the camera, how to write a good script, how to work on the set. I somehow knew film was going to be my lifetime career, but I knew so little about it. So I was always running around with the crew, rather than going to events.

I wrote my first script for Golden Harvest. When I submitted it, they must have thought I was crazy, because it was the 1970s, and it was about gay people. They didn’t know what to do with it, but they realized I wanted to be behind the camera. My first directing project came from Mr. Raymond Chow in 1981. Golden Harvest had a production, Once Upon a Time [Jiu meng bu xu ji, 1981], but the director, Tu Chung-hsun, passed away in a car accident. Everything was prepared, they wanted to go ahead, and Mr. Chow asked if I would be the director. I felt, my god, this is something that just fell from the sky, it is something I should try.

You and Chow Yun-fat received writing credits for Johnnie To’s 1989 melodrama All About Ah-Long. How did that come about?

That was just because I was in the film and I found that there was no script. Which I knew was going to be difficult. Johnnie is a brilliant director, and he has everything about his movies in his head. But sometimes he doesn’t know how to express it on the set, or to say what the dialogue is supposed to be. But he trusted me very much, and he trusted Chow Yun-fat, so he said, “Okay, why don’t you two just go ahead and say whatever you think the characters should be saying.” So I sat down and started writing scenes, I kept writing and writing and finished an entire outline. I gave it to Johnnie. He said, “Great, we have a script.”

From then on, I knew that I should really concentrate on writing proper scripts. I started to write and read other scripts, to just learn and work. I didn’t graduate from film school or anything, so most of what I’ve learned is from the set. I think everything is self-learning, mostly from other people, from life. I’m more interested in characters and relationships, so that’s why I mostly work on things I’m familiar with.

You show that process in Tempting Heart [1999], in which you play a director working through story ideas with your screenwriter.

That’s not what I intended at first, originally I was making a story about a “first love.” But the scriptwriter kept asking me so many interesting questions. She made me think, why do I want to write this script? “First love” is such a common idea, what makes this one different? So the movie kind of formed around that.

Murmur of the Hearts

The films you’ve directed, like 20 30 40 [2004] and Murmur of the Hearts [2015], tend to deal with generational issues. They feature shifting time frames and story lines that weave in and out of each other.

I guess it’s really my way of writing. I believe people live now and sometimes live in the past. Because in our mind, we judge everything from our past experiences. We make decisions sometimes according to what happened in the past. Where we live now is our present, the past is a flashback, and then we have to move on, to the future. We’re always living in a different dimension in the world. When I was writing Murmur of the Hearts, I loved how there are so many things we don’t know, whether in the present or the past, because we are limited by what we’ve experienced. And we remain limited if we don’t learn to let go of the past. That’s how I see my world.

Your scenarios feel so authentic, so accurate, that they seem autobiographical.

Not exactly. The true feeling, yes—that should be autobiographical. And also how I feel or see other people, how I research other people’s pasts, how I try to understand how he or she behaves. So it’s not really autobiographical, it’s just how I spend time and energy on every character, every encounter.

How does being a performer yourself affect how you direct other actors?

I believe in good casting. Every director reading a script must have already an image of how this or that character should be. When you are casting and somebody walks into the room, you have this immediate instinct that yes, she’ll be great or he’ll be just right, this very direct instinct. So 50 percent comes from the right casting. Sometimes I cast non-actors because they are so good, they’re just right for the part. Once they are on the set, with the right costume and the full script, they don’t have to do much.

But you give your performers room to work, freedom to make choices. You’re content to wait for their performances to emerge.

From my point of view as an actress, I always wonder why the director wants me to play this character. I always ask the director, “Why do you want me? What do you see in me?” If the reason is because you believe I’m that character, then you have to believe that when I come in and give my interpretation of the character, and also give my energy and my life, I’m making this character alive, rather than a very stiff interpretation.

So that’s why I believe if I cast certain actors, they will bring their life to that character. If you call that freedom… I also interpret it as you have to make the character alive. In my newest film, Love Education, most of the cast is not very well-known. Well, Zhuangzhuang Tian is very well-known as a director, but nobody knew he was such a good actor.

Love Education

Can you talk about how you developed a visual style?

I worked with Mark Lee Ping-Bing on many films, and then there was a time I tried to work with other cinematographers. Lee Ping-Bing did the same thing, he wanted to work with different directors because he wants to see new things, a new interpretation of life. Film is also the collaboration of so many different artists. The style comes from the art director, the cast, how everybody sees the project, how the story should be told. I love when you’re putting everybody’s thoughts together, and have them merge and present them as one visual piece of art.

I knew Lee Ping-Bing would be great for a certain kind of drama, which is why I asked him to come back for Love Education. It’s a mature subject, and I needed somebody who’s very mature on the camera. The film is about a simple, common family issue, so it could be shot in a very, very simple way. But it needed a touch of warmth and passion and love and understanding. How do you show that? You need a very, very mature cinematographer.

You know Lee Ping-Bing loves to put the camera on tracks. The camera is always moving, everything is flowing, the emotion comes out. He told me he was going to use a zoom lens, which I haven’t used in a long time. He said, don’t worry, I will use it to zoom in and out on movement. He was trying to capture the movement of the family. He tried to use natural light, that’s how he sees things. He also used a filter with a bit of gold and green mixed together, and it gave the film a bit more warmth, a different look.

You’ve also started to work on the stage. Isn’t that how the Johnnie To musical Office came about?

Yes, that was a stage play, Design for Living, that I did about 10 years ago. I was going to turn it into a movie myself. But Johnnie came to see it, and he asked me if he could take over the project. I thought he was kidding, but he was very serious. What I was telling myself was that I saw the film as a musical. Because in a stage play, you pay more attention to tempo, rhythm, pacing. That’s how you adjust the piece. I’d been with it for more than a year, and the more I performed it, the more I thought it was a musical. Johnnie says, great, I want to do a musical, too.

Then I found out how difficult it is to convert your play into a movie script. Because with film, you only have two hours, and the play was more than three hours. So you have to dump a lot of things, you have to work from a different perspective. If I were going to redo Office, I would do it differently. We don’t have enough experience in the Chinese film industry to make musicals. We don’t really have anybody to write songs and lyrics.

So we made Office in a very strange format. I’d write a draft of the script, pass it to Johnnie, he would pass it on to Lo Ta-yu to write lyrics. I kept telling Johnnie, we all need to sit down and write everything together, because the lyrics aren’t just a song, they should be dialogue as well. But we didn’t have the time. It ended up just songs as song, story as story. I didn’t feel it was the proper way of doing it. Johnnie did a great job, the images, the sets, the performances, everything else. But somehow I felt the musical part was a little bit imperfect.

For me, of course working on it was very exciting. Even for Johnnie it was very exciting. He was so excited with the set. The set was really dynamic. We had a good experience. But to me, I want to make it more perfect.

Do you feel that way about all your projects?

Maybe after I finish them, yes, I do. So you see, that’s why I got into a fight with Tsui Hark, too. And Shanghai Blues was such a success. He’s like, “See, why are you so upset?” That’s okay, I love what I do. Maybe that’s why I could continue working for 45-something years.

Daniel Eagan is a critic and film historian living in New York City. He is currently working on the third volume of America’s Film Legacy, a survey of the National Film Registry.