Interview: Kent Jones

While touring America with Jules and Jim in 1962, critic-turned-filmmaker François Truffaut was perplexed by journalists constantly asking why Alfred Hitchcock was so revered in Cahiers du Cinéma. Truffaut believed that Hitchcock was patronized by highbrow American critics due to his association with the maligned thriller genre and his packaging as “The Master of Suspense,” which for them meant a manufacturer of hollow diversions. But further, he felt Hitchcock’s impertinent attitude in interviews and dismissal of questions with facetious epigrams had also led to his reckoning as a lesser talent. “In examining his films, it was obvious that he had given more thought to the potential of his art than any of his colleagues,” Truffaut observed. “It occurred to me that if he would, for the first time, agree to respond seriously to a systematic questionnaire, the resulting document might modify the American critics’ approach to Hitchcock.”

The older man agreed to the interview, which took place in his office at Universal Studios as he completed edits on The Birds. In August 1962, Hitchcock, with 48 films to his credit, sat down with Truffaut, three years into directing and already responsible for three touchstones of the French New Wave. For a week, with the aid of a translator, they discussed Hitchcock’s body of work and approach to his craft, and the resulting tapes were transcribed and edited over a period of four years, with pictorial supplements illustrating their points. Entitled Hitchcock/Truffaut (or Le Cinéma selon Alfred Hitchcock in France), the book was published in 1967 and immediately prompted a reappraisal of Hitchcock among American reviewers.

The book also found its way into the hands of budding cineastes like NYFF director and filmmaker Kent Jones, who now chronicles its impact in his documentary also titled Hitchcock/Truffaut. Sparked by the same sense of professional fraternity, the film, which opens Wednesday, enlists 10 modern directors united by their debt to Hitchcock’s acumen and Truffaut’s foresight. David Fincher, Arnaud Desplechin, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Martin Scorsese, and others discuss what Hitchcock/Truffaut means to them personally and to cinema culture at large. Kent Jones recently spoke to FILM COMMENT about the pragmatic genius of Hitchcock and the myriad ways two like-minded artists can liberate one another.

Hitchcock/Truffaut

I think it’s fair to say that eventually every movie lover arrives at this book. All the filmmakers interviewed the documentary have a history with it, and presumably you do too. Could you talk about how you discovered it and what it’s meant to you?

Well, I wasn’t given it by my father. I don’t remember whether somebody else gave it to me, or if I bought it. But my history with that book is pretty much the same as Fincher’s. The difference is I didn’t have a parent who was encouraging me to make films. I was into cinema from the time I was very young.

How far along were you in your cinephilia when you discovered the book?

Cinephilia is a word I hesitate to use. It was more that I was captivated by film—first by stills of films in books. You know, The Movies, the Richard Griffith pictorial history of the movies. Then by Bogart, very much. Very much. I still am. Then I was really taken with Dick Schickel’s TV series The Men Who Made the Movies which was on PBS in the early Seventies, and Hitchcock is one of the directors in that. That’s when I learned there was such a thing as a director, which was interesting. And then seeing a Hitchcock film—the first one I ever saw was Dial M for Murder. Then just getting my hands on Hitchcock/Truffaut, and like Fincher said, poring through it.

The photomontages are almost as important as the discussions. They really captivate your imagination in a way that film stills that were included in other books at the time didn’t. And it is because, I think, they are put together by a filmmaker. They might be inaccurate sometimes, but that’s not the point. He’s giving you the shot-by-shot breakdown in a way only a filmmaker would. Other people were doing stuff like that, like doing that sequence from Sabotage, for instance—that’s not the same as doing the cornfields in North by Northwest. Same thing with Spellbound for the dream sequence. So that was my entry point with the book. It was a beloved… you know, I took it with me everywhere.

Did you wear out your copy like Wes Anderson?

Yeah, I wore out a couple of copies.

Talking about the directors’ perspective, I found it fascinating in the documentary how the contemporary filmmakers seem to locate their own obsessions when they analyze Hitchcock. Wes Anderson remarks on the subtle and precise visuals. Scorsese sees something religious in the high-angle shots. Hitchcock himself said that he liked to play the audience like an organ, but how much is Hitchcock’s work a sort of Rorschach test, where we see our own fixations?

That’s interesting. I suppose you could say the same of other filmmakers, but in his case there is something so clear about the choices. And when I say the choices I mean the instinctive choices; the choices of material; but also the visual choices, the rhythmic choices, the emphases. And unlike filmmakers who have imitated him. I’m not referring to Brian De Palma, I’m referring to other filmmakers who have imitated him, where you just get kind of a big bowl of nothing.

Going back [to Hitchcock’s films] it’s always a new experience. Every time I see Rear Window. That’s not true for every filmmaker. It’s probably true for certain films by John Ford. In the case of Hawks, he’s a great filmmaker, but I find myself having to sort of leave him alone for a while and then go back to him. Not so with Hitchcock. I find that I’ve been looking at Hitchcock’s films continuously. I don’t really put them aside. Part of it has to do with the fact that they’re all good, I think. And there are a lot of them. Not true of other filmmakers; not true of Hawks, not true of Ford.

Hitchcock did not do anything in second gear. Anything. Even the films that were really hated like Waltzes from Vienna or Jamaica Inn, they are not done like A Song Is Born or Today We Live or Four Men and a Prayer. It’s just not the same thing. He’s sui generis in that sense. There really is nobody else who has a body of work like him in that way. And I guess that he seems so vast, he covers so much territory, literally and figuratively, emotionally and geographically. And spatially, just plain spatially. So, yes, it’s true, I can kind of agree with you: that people can locate their own obsessions.

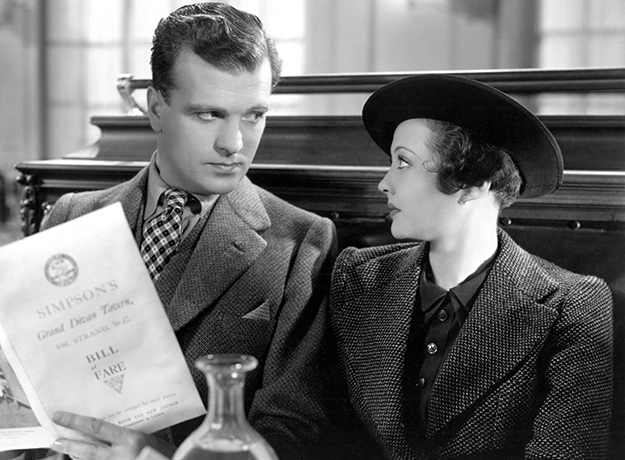

Sabotage

Talking about the Hitchcock imitators, it’s interesting to me in the book when he talks about his love of understatement, he cautions against technique for its own sake, he cautions against abusing cinematic power…

That’s right. Truffaut cautions against abusing cinematic power.

He claims he abused cinematic power in Sabotage.

Yes, well, Truffaut says it and he agrees with him.

So given those things, do you think we tend to name the wrong descendants of Hitchcock? Because a lot of these people who deliver big bowls of nothing seem to be averse to understatement—seem to put technique front and center—and maybe there’s a contingent of filmmakers with philosophical or merely practical affinities to Hitchcock that we don’t credit.

Yeah, but that’s something that is a little bit of a problem in film culture, which is the problem of the word “influence” tripping too easily off the tongue. When people say, “were you influenced by somebody else,” it is never that way. Even during that time when people were asking that question and people were saying, “Yes, I was influenced by Murnau when I did this, and I was influenced by so-and-so when I did that,” that was a very particular moment when reclamation and identifying with a filmmaker of an earlier era that had been seen in a less respectful light than they deserved, was prevalent.

I think the question of influence is very different from that. When people go out of their way and imitate other people, it’s almost always going to end up being something completely different. John Carpenter is the greatest case in point. For all his absolute love for Howard Hawks, he is about 10 solar systems away from Howard Hawks. Assault on Precinct 13 is Pluto and, you know, Rio Bravo is…

Mercury.

Yeah, Mercury. They are not the same, even remotely, but he thought that was what he was doing, and I think a lot of people do that. What you’re talking about is… yeah, Hitchcock is present. And if you’re really into it, he’s present in a lot of filmmakers. When people talk about Truffaut, they commonly talk about The Bride Wore Black and Mississippi Mermaid because they’re films about couples on the run. But when I think of Truffaut and Hitchcock, I think of Fahrenheit 451 because it’s just… Truffaut actually mentions it in the book. The way that he’s setting up the scenes is closer to Hitchcock in that film than it is in others. I also think about something in The Last Metro where Catherine Deneuve is forced to shake hands with the Nazi, and he won’t let go of her hand, and the quick cutting of stuff. Even that, it’s “Yes, sort of, yes, sort of.” Claude Chabrol, yes, of course.

But for the most part, it’s subsumed within the greater flow of people just absorbing lots of stuff. Wes Anderson watches a lot of movies by a lot of different people. He reads a lot. He thinks about a lot of different kinds of things, so all those things are coursing through him. And let’s be honest, when you’re making a film, it’s not just films that are in your influence. It’s like Godard said in an interview in Cahiers, I was influenced by my father more than I was influenced by Mizoguchi or something.

Hitchcock/Truffaut

Near the end of the film, we hear Hitchcock speculate that he may have let form limit him. That maybe he should have been more experimental with character and performance. Can you comment on that? And also whether you see any parallels with Truffaut in terms of self-limitation?

It’s a poignant question because it’s generated by the fact that he was so disrespected in his lifetime by critics until very late, and not taken seriously, and he thought: “Well, if I had made films that were more character-based and less oriented around the suspense form or the rising arc form of narrative, then would I have been taken more seriously?” But then of course he’s also talking back and forth to himself, and he’s also asking Truffaut, in essence. And that’s what I wanted in the movie. This question—“Am I an artist? Did I really do something substantial?” And Truffaut’s saying: “Yes. Not only did you do something substantial, but if it weren’t for you, I don’t know if I’d be making movies.”

And then he’s also saying: “Of course I suppose that any artist is limited by their form is limited to one area.” And he’s right. Hawks kept returning to the same ideas. At a certain point later in his career, he was returning to them because he thought: “Well, it worked in the last one, I think it will work in this one.” But also he was just interested. He kept returning to the same emotional configurations. The man and the woman. The man who’s ambivalent and the woman who’s initially resistant but then who dives in, and the man who’s ambivalent and has to confront his own fear. And the friend, you know, the weak friend. And John Ford’s the same, and Marty [Scorsese].

In Truffaut’s case, I don’t think that he is any more or less limited than any of the other people that we’ve just discussed, or Godard for that matter. I don’t mean limited in a pejorative sense, I mean limited in a sense of looking at an ultimate career. Truffaut is a much stranger, thornier, weirder artist than he appeared to be when he was alive and working and spitting out one or two movies a year…

And Godard was calling him a sellout.

People have this sort of Lennon and McCartney thing in their minds, and it’s obvious which one was which but… Truffaut’s not Paul McCartney. [Laughs] The idea that he was making the kinds of movies that Godard was criticizing is just bullshit rhetoric. I don’t think anybody was making a movie like The Woman Next Door, or Two English Girls. Those are very straight films—and very powerful.

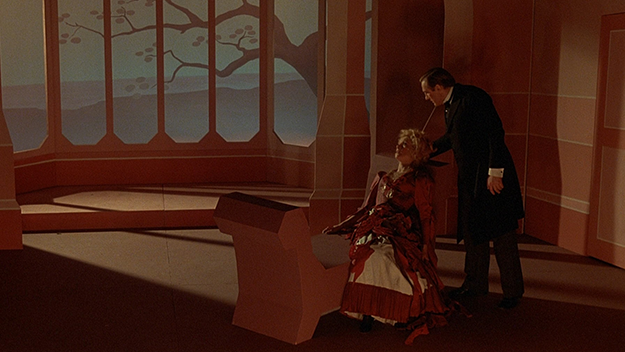

The Green Room.

Well, The Green Room, yes, because that’s the weirdest of all of them. But Fahrenheit 451 is for me an incredibly powerful experience. So is The Woman Next Door, so is The Last Metro, actually, the last time I checked in on it.

The Last Metro

You sort of just answered this, but how did Truffaut and Hitchcock rescue each other? Because that’s another theme of the documentary, how they each filled a void for the other.

In the case of Truffaut rescuing Hitchcock, I think it’s obvious. That was the mission.

Rehabilitated his reputation.

I don’t even really know about rehabilitating it, but redefining the ground beneath him so that he’s seen in his proper place. Not just as a great filmmaker, not just as the greatest filmmaker who ever lived, which is what Truffaut said in his letter, but as a bedrock for all other filmmakers. There aren’t that many directors you can say that of. You can say that about Griffith, you can say that of Murnau, probably, you can say that about Ford, and you could certainly say it of Hitchcock. Méliès and the Lumières, sure, but that’s before.

Hitchcock rescuing Truffaut? I don’t know about rescuing, but giving him a window or a pathway into making movies. So that he’s thinking: “What would Alfred Hitchcock do?” And he’s like: “Yeah, I’ll buy that.” I don’t think he’s thinking: “What would Jean Renoir do?” Even though for him, Renoir’s probably the greater artist. He’s thinking Renoir is a great artist because what he’s doing is finding a cinema, a form of cinema that isn’t involved with narrative, per se. It is, but where it’s more involved is in the immediacy of the moment. The micro-event, you know?

Contingency. Things like that.

Right, contingency, there you go. That’s always a good word. You’re obviously a reader of Pragmatism. There’s a good moment in the tapes that we tried to include in the movie, but there just wasn’t really a place for it. Hitchcock suddenly says to Truffaut: [in Hitchcock’s voice] “Why is it that Renoir cannot tell a story?” And Truffaut says: “Well, I don’t think he really is interested in telling a story.” And Hitchcock says: “There’s just no tension in his work at all. And you know, it’s been a long time since he’s had a hit.” And Truffaut says: “Well, there’s Grand Illusion.” “Yeah, that’s a long time ago.” [Laughs] It’s a very funny exchange.

Could you expand on Scorsese’s statement in the film that Psycho anticipated the Sixties?

Marty actually talked about that in the interview. Olivier Assayas did too. It’s another thing that we were going to do in the movie, but it’s very kind of slow and cumbersome and didn’t really bring much to the party. It’s not about giving something new about Hitchcock, some new revelation. What it is about is placing people within the framework of that moment and moments that followed so that they can understand the history of how and why these conversations happened, why they were important, and how things have evolved since, the acting question which is very important and changed the way movies were made. And in the case of Psycho, on the one hand you have Fincher saying he threw the grenade into the conference room and destroyed all the rules, and on the other hand you have Peter [Bogdanovich] saying: “We just weren’t prepared for that. You know, I mean you have no idea what it was like sitting there [watching Psycho in 1960].” And then on the other hand you have Rick Linklater saying it’s a small story, but it’s the shock of it. The shock of saying to an audience, “You’re used to seeing this,” as Marty puts it, “but this is possible.” You know, at any minute. At any moment. You know, death is possible. It comes. The shock comes, you know. What seems permanent doesn’t last.

That’s something that’s very present in Hitchcock, period, throughout his entire career, but Psycho is the movie where you really feel it. And Marty enumerates it better than I could, in talking about what it, in retrospect, opened the door to—a way of seeing that turned out to be extremely conducive to a series of shocks. To the point where people were like: “Okay, what next?” You know? I mean I remember, like, I was too young to remember JFK being shot, but I remember Martin Luther King being shot, and then Bobby Kennedy three months later. You’re just like, Jesus, you know? And looking at it from the perspective of right now, what’s just happened in France… That’s time passing. Every moment allows you to look back on every other moment in a new light.

Hitchcock/Truffaut

A crucial part of the Hitchcock mythology is this story that his father had him locked up for misbehaving. And in the documentary we hear Truffaut’s father did the same thing to him. How formative were these experiences?

Well, you’re talking about two very different things. Somebody when they’re three years old, stealing a cookie or something like that, And their father saying: “All right, we have to punish the bad boys,” and putting them in jail for 30 seconds. That’s one thing. Stealing a typewriter and filching money from the Boy Scouts in order to pay for your screening series and having your father deliver you the police, that’s something else when you’re 13 years old. That’s a whole other ballgame. For Hitchcock that’s the mythology that he created. That’s his public persona. So it goes along with: “Actors are cattle.” “I’m bored when I’m on the set.” “I’ve designed it all beforehand on flash cards and storyboards,” etc. You know? The “MacGuffin” is kind of like that—it’s kind of interesting, but not that interesting, you know? [Hitchcock’s childhood anecdote] is along those lines, but when you contrast it with the real hell that Truffaut went through, it’s different. I’m afraid of the police too. I mean, most people I know are. I don’t think there’s anything terribly unusual about it. But he made a thing out of it.

Let’s talk about Hitchcock’s signature cameos. He tells Truffaut in the book that they were born of necessity, because he didn’t have enough extras, so he was needed to fill the frame, so to speak.

Yeah, that’s it.

Next it was superstition, and finally obligation. Could you talk about how Hitchcock made a commodity of himself? Or even a mascot.

It was a smart move, because these guys from that generation had to find a way of building a wall around themselves so that they could make the films that they wanted to make within the framework of that system. So turning himself into a Master of Suspense very early was a really smart idea.

And kind of unprecedented, right? There was the vanity of Griffith monogramming his intertitles, but this is something else.

Yes, it is something else. Lubitsch was known for the “Lubitsch touch.” DeMille, of course. And Ford, too. Capra. But really Hitchcock was the one who turned himself into a… you know, the profile, the weight. And he did a very good job of a building a wall around himself. But the downside of it, of course, is [the impression] that he’s just a cartoon character. He’s just a guy who makes “Saturday night at the movies.”

Hitchcock says he’s wary of literature, which is interesting because a lot of his colleagues are looking for literary sources to adapt. And he’s more focusing on short stories and pulp stories. He claims that he reads them once, takes what he needs and moves on, and he couldn’t even tell you what du Maurier’s The Birds was about.

That’s right.

The Birds

Why do you think that is? Literature for him is too complete, or too dense, or too well-known?

There’s a moment in the tapes when Truffaut says to him: “You know, you would have been the perfect director to do Dostoyevsky, to do Crime and Punishment.” And Hitchcock says: “That is something I would never do.”

“If I did, I’d do it poorly.”

He also says: “If you were going to do Crime and Punishment, you would have to film every single word of it.” And what he means is, it all functions as a whole. Which is why I think he just finds it so comical that people take these novels and do these—I mean, I love King Vidor, but War and Peace is… It’s fine, it’s just not an adaptation of Tolstoy. It’s something else. It’s like taking Tolstoy and events from Tolstoy and turning them into a big spectacular adventure movie.

When, when Truffaut railed against the tradition of quality, this is what he is talking about, right? These pedigreed literary adaptations that are just kind of…

He’s not talking about the practice itself, he’s talking about certain filmmakers taking novels like La Symphonie Pastorale, The Red and the Black, Devil in the Flesh… It’s like Hitchcock says in the movie: “Psycho was just pure film. It wasn’t an adaptation of a great novel or a great performance that stirred audiences.” People are going into [an adaptation] with the expectation of something based on the novel that they’ve read: they’re walking into A Place in the Sun with an American Tragedy in their head, and seeing the movie version of it. It’s not that Hitchcock’s mistrustful of literature, he just had a very keen understanding that literature exists in another world from cinema, and I think he’s 100 percent right about that. There is such a thing as doing a very good adaptation of a novel: Age of Innocence comes to mind, as does House of Mirth. They’re both very different, but they’re both excellent. That’s because they function as films. And then you have The Great Gatsby. [Laughs]

Hitchcock was especially mistrustful of the plays that he was sort of coerced into adapting.

Yeah, that’s true, but they’re all good. Juno and the Paycock is a really interesting film. And Dial M for Murder in 3-D is a genuinely great film.

It’s noteworthy that so many of his silent or very early sound films were taken from plays, because he says that dialogue should only be resorted to when it’s impossible to do otherwise. So he was taking a play, which is dialogue-driven, and taking out the dialogue.

Yeah, but he also had an idea that he said which was very, very true: “Film did not have to change as drastically as it did when sound came in.” It’s a very, very important thought. Because it could have just been used as a tool, and they could have built on the incredible sophistication that some filmmakers arrived at with silent cinema. But they didn’t do that. And that’s interesting because, in a sense, what Hitchcock did was he proposed that as an alternative history through his own filmmaking. I think that Brian De Palma’s kind of alone in the sense that he walked into Hitchcock’s own aesthetic universe as if it were a universe of its own, apart from all the rest of filmmaking. And he built his own universe out of it. It’s like he’s a planet in alignment with Hitchcock, and not really anybody else.

To a certain extent John Ford fulfills that too. Hawks, no, that’s something different. Although the movement of human form within the frame is the central event in Hawks, and the fact that he started in silents is absolutely present in his work 100 percent. But Ford and Hitchcock really were the ones, and Hitchcock in particular, to give you an alternate version of what’s cinema. And the other people who followed that—you could say Sam Fuller did. You could say Kubrick did. Marty to a certain extent. I don’t know. It’s an interesting question.