Interview: Gianfranco Rosi

“From the shores of my peace, luck, games, and satisfaction, someone with a horrible force of war, which I am terrified of, is trying to pull me, and pull me away.”

—Zlata Filipovic, a 12-year-old Sarajevan girl, Sarajevo: The Portrait of the Siege

On September 2, 2015, the world was shaken by the image of a drowned Syrian toddler lying face-down on a Turkish beach. Immaculately dressed, the little Alan Kurdi, a victim of the ongoing civil war in Syria, had washed ashore like a jellyfish—a harrowing sight of innocence consumed by the 21st-century death machine. A global outpouring of grief and rage ensued through sensational headlines and a long-overdue discourse on human rights, forging the image of Alan’s lifeless body into an emblem of the greatest humanitarian disaster in recent history, as haunting a representation of contemporary apocalypse as Nick Ut’s iconic photograph of the napalmed girl during the Vietnam War. That Alan’s death has bettered Europe’s response to the refugee crisis is strongly debatable, but one thing is sure: his image is indelible, waiting for us in the hallways of history as a grueling testament to our times.

It is precisely the artist’s mission of recording history, of giving form to the present moment, that Gianfranco Rosi has carried out boldly and thoroughly in his new documentary Fire at Sea. In engaging with the migrant crisis, he stands at the polar opposite of sentimental popular journalism, instead proposing a deliberately withdrawn and poetic meta-reflection on the collapse of modern civilization. Framed by the simultaneously jaunty and melancholic coming-of-age of 12-year-old Samuele, Fire at Sea takes place on and around the island of Lampedusa, the nervous frontier between the irreconcilable poles of a disintegrating world: a guilty, brutally reactionary Europe, and the eternal site of warfare and bloodshed that is the African continent.

A citizen of the world who was born in Eritrea and has lived in Turkey, Italy, and the United States, Gianfranco Rosi is a prime embodiment of the lone venturer, crossing remote wildernesses to take us into the heart of complex and contradicting human experiences. On the day of the U.S. premiere of Fire at Sea at the New York Film Festival, Film Comment spoke with Rosi about his rigorous dissection of contemporary anxieties and his cinematic odyssey.

Fire at Sea

Beyond its portrait of Lampedusa as an epicenter of the European migrant crisis, Fire at Sea is a study of loss of innocence and the end of childhood. Throughout the film, Samuele’s body progressively slips away from him: first he is diagnosed with a lazy eye and then he begins to suffer anxiety attacks. Samuele’s physical condition emerges as a metaphor of his unawareness of Lampedusa’s other face, and at the same time suggests that he is subconsciously affected by the situation. It also becomes a metaphor of our collective indifference toward the refugees, and confronts us with our own fears and human responsibilities.

When I met Samuele, I had an incredible immediate contact with him and I felt that he was a special kid. Since the beginning, I wanted the film to be about a kid and I wanted to switch points of view. I wanted to tell the story of the migrants through the islanders, and I thought that having a kid would also give me some freedom to narrate this dimension, because a kid can be unaware of certain things happening around him. So I wanted to somehow discover all this tragedy from the point of view of the kid.

When I was filming him, day by day, I discovered his inner world with an incredible sense of space and suspension. And that somehow rang a bell with what was happening in Lampedusa, the feeling of the tragedy. In the end, the film is like a coming-of-age story. The tragedy is the discomfort of a kid to face life and the unknown—it’s a typical age, 12 years old. There’s this incredible sense of wonder. And when I was filming him, I felt that his world was bringing me constantly to a world that we are still not able to accept. The tragedy comes and passes by Lampedusa, but we’re not able to interact with it. The film accentuates very much these two different worlds that touch each other but never interact. And then there is the figure of the doctor who somehow creates a link between these two worlds.

Four years ago, the border was moved to the middle of the sea. Before, the migrants used to arrive to the island. But for the last four years, they’re being brought into the island. So when they arrived to the island by themselves, they interacted with the islanders. But this interaction has now been lost and became a separation between two realities. So Lampedusa somehow became a metaphor of what Europe is right now: these two worlds that collide but cannot interact with each other.

People ask me why Samuele doesn’t interact with the migrants in the film. Because he does not in real life. If this were a fiction film, there would be a strong temptation to put Samuele in contact with a migrant kid of his age. I was free to use reality as a conductor in the film. So when people ask me, “Why is it not there?” it’s because it never happened in reality and I’m not going to change what reality is. Otherwise it wouldn’t be a documentary.

Did Samuele ever question your process?

No, never. It’s just that at the beginning, he was always looking at me when I was filming him. So when I was filming the two kids together, Samuele and his friend—they later fought and stopped being friends, but I don’t explain that in the film—there was a lot of showing off. And then one day they were playing and I was filming them, and they started to do these fake things. So I just packed the camera and left. I didn’t say anything to them. And the next day, they came up to me and said, “Why did you leave like that?” and I said, “Well you were boring me. I don’t want to waste my time. I’ll start working with other kids.” They said: “Who?” I said: “It doesn’t matter. I’ll find two kids of your age instead of the two of you fighting in front of the camera.” For two weeks, I disappeared completely. And when I came back, they completely forgot and they became really natural. From then on, Samuele just began to do his own thing without acting, and he completely forgot the presence of the camera. So I provoked them in order to be accepted without being pleased constantly.

Fire at Sea

The opening of the film, with the shots of the spinning antennas that play over an emergency call from a migrant boat, and the ghostlike, disembodied images of a search ship, really conveys the feeling of separation and alienation that prevails in Lampedusa today. You emphasize the migrants’ absence rather than their presence—they’re like phantoms moving through the night. At what point in the process did you capture these opening images and why did you decide to begin the film with them?

Technology is somehow very present in the film. There’s the [ultrasound] monitor of the doctor, for example, and other elements of technology. Again, I wanted to underline in the film that these two worlds never meet and so there is this mechanization or militarization, this machine that they have set up to “protect” us. And then outside this radar or spectrum, the migrants are like aliens. Of course there’s an abstraction with those shots you’ve mentioned, because it’s not like the migrants’ voices are captured by those radars; that’s done in the editing. But I wanted to underline the idea of separation again there—the fact that they’re asking for help is something so weak and powerful and desperate.

In the end, the film is a cry for help. The film doesn’t talk about the whole background, reasons, or politics of the tragedy. There’s just a few numbers at the beginning. And then it’s up to the viewer to interact and make his own connections. It’s like a Giacometti statue, so thin, and it’s up to you to create the space that’s missing. And for me, it’s a question of how thin I can go with this before it crashes. So that’s always a challenge for me in a film. How much less can I say before it becomes nonsense or indulgent or whatever? So you have to always keep this sense of awareness of how much to say and how much not to say. But for me this always comes from the emotional mood and the inner world of the people I’m filming. This is what makes the film go on.

The whole film is built so that we arrive to the tragedy, to death, at the end. I never knew where this was going to be in the film, but when I filmed it [a mass rescue operation scene at the end of the film], the film was finished for me. I didn’t have the energy to keep going anymore. I had never filmed death in my life before. With my first film [Boatman, 1993] it was this sense of death being part of life. But here it was a tragedy, and I felt the importance of showing to the world that this is one of the biggest tragedies that Europe has faced since the Second World War. So the film wants to create an awareness of this mass death and this scene became a symbol of that—it’s like a monument to death.

The whole thing, from the beginning to the end, frame by frame, story by story, character by character, mood by mood, is a long journey to arrive to this moment of tragedy. So it’s like a narrative arc to arrive to that point. But then it was not possible to have the end of the film there and I had to re-create another ending through mourning. We have to mourn death and respect that moment. And I had to respect all the people that were part of this film. There was a transformation of all of them, something else happening in their lives, you know—the death bed, the ritual of death, the song of death… Samuele in the beginning kills the bird and at the end, he talks to it. And in that scene and that dialogue, there is the truth of the film. The bird is telling a secret to Samuele, and Samuele is telling a secret to the bird. So each person has started to fill that dialogue with their own words, and there lies the secret of the film, in that unspoken, incomprehensible dialogue. I use the reality of the narrative and the language and tools of cinema to convey this.

Fire at Sea

For me, the most devastating images of the film are those of migrants looking into your lens, when they realize they’re being filmed. This reminded me of what the French critic Antoine de Baecque writes in his book Camera Historica about images of Holocaust survivors staring into the camera, like those featured prominently in Night and Fog. De Baecque argues that these images embody the history of the century—he calls it the “unrepresentable 20th century”—and emphasizes that cinema had to change after them because they brought about a tremendous loss of innocence. The looks in your film made me feel the same way, as though I was staring at the face of death, as though cinema had to change…

Yes, you can’t film death after the Holocaust. That’s what Adorno said, I believe. But I felt somehow that we are living another Holocaust and the film is a witness to something contemporary that is going on. So it’s important to have that contact with the eyes and the contact with death, because that’s another moment of tragedy. We are in this moment of history and we cannot afford to turn to the other side and say: “We don’t want these people here.” Sorry that I have to put your country now in the middle of it, but what’s happening in Turkey is unacceptable for me. You know, the fact that Europe is bargaining with a dictator to keep all those people [the Syrians] there. Most of those people have no future in Turkey. They live on the streets in Istanbul, and the kids are working in factories for one Turkish lira a day. And we, as Europe, are constantly bargaining the rights of these people. Countries like Hungary and Poland are saying they’re going to create a quota system, so if these people arrive in Italy, they’re Italian business [i.e., responsibility]. This is the collapse of Europe. We don’t understand the rights of individuals to ask for asylum. We are killing the identity and unity of Europe.

How did you manage to keep the camera rolling when you had people confronting your gaze with such intensity?

For me, it was a big challenge to decide to film this. I had to show that in the back of these numbers, they’re human beings, that there’s inspiration, fear, and hope in their eyes. When they are in front of the camera or when they are getting searched and they look at me, in this moment, I am somehow part of the system. My camera embodies the system there, because I never asked them whether I could film, I imposed myself. But then I had to give something back to them, in a way, and I had to give that back in the moment of death. When the Nigerians are chanting in the film, it’s like witnessing history again, you know, it’s a moment of reality, of epic dimension. In that three-minute song, there is the destiny of a people and the tragedy of their exodus, which, most of the time, ends with death. They’re escaping death in the face of death, and they’re facing the unknown of the sea—the Mediterranean sea became a tomb, a cemetery, with 25,000 dead bodies. It’s a Holocaust and we are part of this.

Fire at Sea

You act as your own cinematographer and sound recordist, which is unusual. I must say that you come across as a painter to me because of your incredibly meticulous and impressionistic approach to composition, camera movement, and lighting. I’m thinking specifically of the scene in which Samuele and his friend are shooting cactuses with their slingshots. How did you manage to get so much coverage of that scene? In other words, when you’re alone and making decisions in the moment, what prompts you to move your camera to a new angle, and how do you take that risk every time, given that you could potentially sacrifice reality in that technical transition?

I have a lot of time before I start filming. I know that the kids will go there and play. It’s a ritual, and you have to be able to enter the ritual constantly. When they do the slingshots and all, it’s part of the ritual, and I know it’s going to happen. So when he told me his slingshot was broken and that he needed a new one, I filmed him building a new one. When he says, “We’re going to play today with my friend,” I follow them. At a certain point when they were cutting the cactuses, I said: “Samuele, don’t do that to the plant. Why are you doing this? Come on!” He said: “We are building the face of the enemy.” Then I started filming the whole thing, and it became that scene, you know. When you change frame, it’s because you know that something is already happening in that new frame from the editing mindset. “Okay, so I covered this” and then you move onto another shot to get the dynamic. When they move to another plant, you’re here stuck with the frame and then you go back and move the camera to where they’re doing it.

So it’s a simultaneous process for you of shooting and mentally editing those shots together?

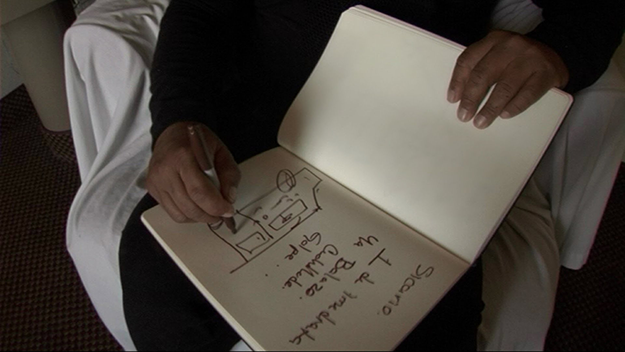

I can change the frame once I know that something’s happened that has a beginning and an end. Otherwise, it doesn’t work. So I have to follow a constant story and make sure that the narrative exists. Frame means for me a cycle of complete story that goes from A to B. And once you have all of these frames happening from A to B, these are complete shots. Then you have to think about how this shot connects to the next one. [He draws in his notebook.] So if this is Samuele, and this is the ship arriving, and this is the doctor, you have to find a sense of continuity within that. You see that this note is not so different from that note, and you create the harmony. This note is continuous with that, and that note leads to the next one. And this space is important: two notes and a silence. This is another space that has to be filled in the film. And then something happens that fucks it all up and you start filming again.

But you have enough time in your hands to process what you’ve shot and remedy any gaps you may find.

Time is my biggest ally on a film, more than money, more than anything. I need to buy time. Because I know when I start the thing but I don’t know when I’ll end it. I don’t know what’s going to happen, it’s a journey into the unknown. It’s a labyrinth where I have to find the exit at a certain point. But when I filmed death, that was it. I couldn’t film anymore. When I filmed death, something happened to me and I said: “I don’t want to keep filming.” I called my editor and I said: “We have an island, we have the story of a little kid with other people around him, and we have the story of the migrants arriving. These two stories never encounter and then there’s the story of the phantom boat—aliens going to save aliens. These are the stories in the film and it’s all I have right now. Very simple. There’s no plan B. Either it works or it doesn’t.” And then I said, well, to put these two stories together, we have Samuele, the doctor, the DJ, the migrants arriving, the boat going on this mission. All these stories have to interweave to arrive to the moment of death. All of this is building up emotionally, like a narrative, like poetry, but not like an essay. It’s constantly an interior mood. There has to be a narrative arc and all of this has to have a completion. So it’s like a game of mirrors that open up and each one contains a different plane of reality.

El Sicario, Room 164

I’m fascinated by the performative aspect of your films, by which I mean that they all show at least one subject in a state of “cine-trance” or “cine-therapy,” pouring their hearts out to the camera in a way that they would not in real life. There’s the old man in Sacro GRA [2013] who delivers that haunting monologue about his obsession with the world of insects. There’s the doctor in Fire at Sea who carries the whole weight of the tragedy and exorcises his demons before the camera. And of course, this idea of performance reaches its pinnacle in El Sicario, Room 164 [2010], in which the titular protagonist goes through extreme states of catharsis and enlightenment as he relates his larger-than-life story to you. As a filmmaker, how do you trigger those moments of self-revelation?

The only thing that I do is to follow my instinct to put the camera there at the right moment and to create the trust. In El Sicario, I had to create a lot of trust and I didn’t have much time, a few hours maybe. But without that moment of two people looking into each other’s eyes and saying “Okay, I know a thing or two…” If there’s no trust, there’s nothing. In fact, people ask me: “How do you disappear in your films?” But I don’t disappear, I’m constantly there. I’m the one who interacts with them. It takes two people to create that. And in that moment, I change, and they change, and the camera is changing everything and transforming reality into something else. There’s a constant transformation of reality into something else in my films. I need to be aware of that. When the camera is there, things are going to change.

The camera is a catalyst for introspection.

Something’s going to happen, and that’s what I love about documentary, because every moment that you see on the screen, I never thought it was going to exist. It was never on my mind. It was a revelation of something. I always said that my films, and especially this one, were made on their own, you know. It’s like those plants that self-reproduce. How do you call them? [He looks up the name on his phone.] You see, it’s a virginal reproduction. There’s no contact.

Sea urchins reproduce that way too.

Yes, so there is no contact, no interaction, so it’s the perfect metaphor. My films are self-reproduced. I only need to have the ability of bringing the camera into that moment, and that’s it. But I don’t induce that moment myself. That moment happens and it happens most of the time in a very beautiful way.

You probably induced that moment with the doctor by spending so much time with him beforehand.

The second he started to tell me his story, it was so strong that I was crying when I was filming him. And he was crying when he was telling me those things. When Samuele visits the doctor, it’s a magical moment between the two of them. I just put the camera there and I said: “I don’t know what’s going to happen but something is going to happen.” The two of them had never met. And then Samuele started to talk about his anxiety attacks. No writer could have written that. No director could have directed that. And no actor could have acted that in such a way. Also, the sicario, when he sketches in his notebook, no actor could have acted that. Often people say: “Oh, he’s an actor.”

Fire at Sea

There’s an innate sense of acting in all of us that manifests itself in front of the camera.

It’s what Aeschylus used to say, you know: “The best acting is an awareness of acting.” So this is an automatic form of acting. To act without knowing that you’re acting somehow. It’s like going to a therapist. When you go to a therapist for an hour, in that hour you say things that you would never say in the rest of the day. You have the force in that hour to go inside yourself and things come out. And the next day, other things will come out, which are different than before. The first day, you say certain things. The next day, you say different things. But you’re forcing that moment to do something to you. The camera also acts like that. Somehow the camera allows those things to come out. And then it’s no longer a question of whether the person is acting or not acting or lying or not lying. Of course in that moment, he or she does something because there is a camera. But the camera brings out this form of self-awareness, which is very important for me.

In your films, you record the workings of idiosyncratic enclosed universes that play out like microcosms of the larger society. Often you live in those communities for years to immerse yourself fully in their reality and depict it accurately on screen. In this respect, could one say that your work as a documentary filmmaker resembles that of a sailor, given the sense of solitude and sacrifice entailed by your lifestyle and also the fact that the sea is an important visual and narrative motif in your cinema?

I suffer the sea, you know. [He laughs.] When I was filming Samuele on the boat and he’s throwing up in the sea, I probably threw up five times before him. So I never felt like a sailor. What is important for me is that in all my work, there is a mental space, which is somehow the border—there’s an empty space that I have to fill with stories. So there’s always an encounter with a place, and then that place becomes a mental space, like in Sacro GRA, like the desert in Below Sea Level, the moon also, the sky, the city of death… Basically it’s a real place that has to be transformed.

I feel more close to a figure like Bruce Chatwin who goes on these journeys, taking notes, and the camera becomes my pen, in a way. And it becomes an adventure of life. For me, every film is a big change and there’s a lot that I have to give up for every film. I was in Lampedusa for a year and a half. And every time, you start to understand a different dimension of yourself. Somehow I give up all sense of identity when I’m in a place, which is what an artist must do. An artist must give up all his identity in order to discover something else. I hate the word “integration” but… What I love about New York, at least the New York of 20 or 30 years ago, was the fact that you had to “integrate” in New York. You had to give up something of your own past and your identity in order to belong and discover something else. Our culture sets things up so that: [He draws in his notebook.] “I’m here, you’re here, I’m right, you’re wrong, in order for me to accept you, you have to be exactly like me.” And that’s horrible. That means building walls, both mental and physical.

It’s like what Obama said in his beautiful speech: “If you build a wall, you build a prison for yourself.” And if we don’t understand that, our society is going to collapse. And now the way we talk about immigration in Europe is not that different from the way they talk about it here. There is a very strong xenophobic feeling. When I was growing up, for me the world was one space in which everybody had to respect each other, and every time I moved, I experienced such a beautiful change of culture—the Muslims, the Christians, the Protestants, the Hindus: for me, it was just one world. And now we are living in a world of separation, separation, separation. This is going to create an incredible explosion. And it’s already started.

Fire at Sea is in theaters now.

Yonca Talu is a filmmaker living in New York. She grew up in Istanbul and recently graduated from NYU Tisch.