Interview: Errol Morris (Part Two)

[Last week on our interview with Errol Morris about Wormwood, his upcoming multipart series about Eric Olson, son of a military scientist who died in a mysterious fall: “Is it a fact of the matter that the CIA or people working for the CIA tossed Frank Olson out a window at the Statler Hotel in 1953?” … “I don’t always like my films, but I kind of do like this one because it expresses a lot of things that interest me.” … “A source is something that you protect at all costs. And why? There is an element of self-interest as well.” … “There are reenactments and there are dramatic scenes which are really not reenactments at all.” … “It’s easier to cut with 10 cameras.” … “The orangutan did it.”]

Wormwood

Wormwood shows how these events must have been traumatic for Eric Olson—because when does he ever get his sense of an ending? It’s a nightmare, that this mystery and cover-up could go from one decade to the next.

There’s endings and there’s the related concept of closure. I always had this idea that Adam complained to God, “What about closure?” And God thought for a moment and said, “Oh… How about death? Do you like that for closure?”

You pose a wonderful interview question to Eric: “What would you say to Hamlet?” How did you lead up to that?

I asked that same question of Donald Trump in the short film I made of Donald Trump. I asked him, “What would you say to Charles Foster Kane?” What would you say to this central imaginary character if given the opportunity to do so? It made me think about Hamlet, but the most terrifying aspect of Hamlet, or one of the more terrifying aspects of Hamlet, is that this is your family, this is your court, this is your home, this is your state. And it’s infected. There are enemies everywhere. It’s not so much that your father has been killed, murdered. But that people, all the people, somehow have participated in this murder and might even be plotting your own.

That complicity is a special source of terror. That idea of the government committing atrocities and Eric’s father being party to it but clearly not wanting to be party to it anymore…

I say that to Eric at some point. I say, what makes it even worse is he’s complicit in all of this. If I was going to defend it—and I should defend it, I made it and I even like it—it’s complex and it raises a lot of complex issues.

Wormwood works itself up to the kind of shocking revelation a feature-length documentary might be entirely structured around. But here, by the end, it’s just one of so many bad things, this idea that the government might have killed someone.

And covered it up.

And covered it up.

Or that the government is routinely involved in killing people and covering it up.

Do you expect any reaction from the government? Because as far as descriptions or accounts of that happening, this is a very persuasive one.

I don’t know what’s going to happen. It would be nice if something happened. We live in such a strange turning point in American history, maybe the culmination of so much in American history. We’re all speechless. At least I am.

I’ve read that when we are so surrounded by falsehoods or untruths, our brains just eventually shut down in a way. That’s the environment this presidency seems to create.

I don’t think you ever give up on truth. If there’s anything that has any dignity to it in human life, it’s truth. We maybe don’t always grab ahold of it but we know that there’s an issue here that one should pay attention to—that there’s a difference between truth and falsehood. The search, the attempt to find the truth, gives a kind of dignity to human existence.

Wormwood

And it makes Eric a noble character.

A heroic character.

And a tragic one because in pursuing this, he consumes himself.

Tragic heroes are supposed to destroy themselves in the process. I don’t know if the word “supposed to” is quite right, but it’s often part of the story.

Was the process of making the film somehow therapeutic for him or just aggravating? How long were you interviewing him?

About two years, because we first did the interviews and then we did the interviews with additional characters. Sy Hersh was the last of them—he was very difficult, he was always very difficult, still very difficult. He wouldn’t agree to do the interview, and then he did agree—it was the last of the interviews. And then I shot all of the drama. The drama was the most expensive step, so it was initially hard to get the money to do it. It wasn’t even clear whether it was all going to work. I mean, think of all these elements. I was lucky. You have this home movie material—Frank Olson was an amazing amateur photographer and took all of these home movies. You get a feeling for how much he loved his family, how involved he was with his family. All of this material, strange material, of Eric digging, endless digging with a shovel. Just amazing archival material from the ‘50s and from the ‘70s and afterward.

Since you had done the interviews first, did that change what you then decided to film as a drama at all?

We had written part of the drama. I wanted to try to avoid reenactment. So, for me, reenactment is you have an interview subject, this talking head, sitting in front of the camera. Sometimes we would refer to them as “Jogger and Silk Stockings” reenactments. You have the talking head describe some scene and then you see it. It’s see/say. And to be sure, there are elements of that in Wormwood. But again, there are elements of it in which there is none of that. There’s none of the drama being set up explicitly by an interview.

Did you talk with Peter Sarsgaard and the rest of the cast about playing these people as characters?

Yeah. They are characters they’re creating on screen. I had amazing actors, I might add. I had a really amazing collection of people.

Thinking about the casting, I thought you had seen Experimenter, right?

Of course I did. At the time, I was thinking of casting Peter [Sarsgaard, as Frank Olson], and I’ve always liked Peter. I saw Experimenter and, ironically, Peter’s performance of Hamlet in New York. I mean, I would have seen Experimenter anyway because of my interest in Stanley Milgram, but in addition there was this overlap with someone that I was really interested in casting as Frank Olson. I had a great casting director, Cindy Tolan, and amazing performances. Christian Camargo as Lashbrook is great.

He doesn’t even have to say a word. He has a face out of a graphic novel—he looks like an etching or drawing.

Yeah, he does. Bob Balaban, Molly Parker—an amazing group. And the difference is they’re not bringing to life an interview, they’re bringing to life a script.

Experimenter

But it’s an interesting kind of script, because it’s very much selected scenes from a larger story. Fragmentary, like the story itself. So I wonder what that’s like for an actor.

The actors said they were unsure—everyone enjoyed, at some point, working on it, but they were unsure of what it would produce in the end. I probably should add myself to that list.

It’s also remarkable the way Eric is piecing together his life and his story.

His Ph.D. thesis at Harvard was on collage theory.

That’s collage theory as a form of therapy?

To the extent that I understand it.

Did you read his thesis?

I did, yeah, we have a copy of it. On a very simple level, he got all of these Time/Life books and encouraged people to cut out their own collages. I was thinking of writing something about it. My ultimate defense of reenactments in The Thin Blue Line, I would say to people, “Well, you know, consciousness is a reenactment of the world, inside of our skulls.” And the process of how we come to understand the world is a collage process, if you want to carry the metaphor along. We are constantly taking bits and pieces, that’s what detective fiction tries to capture in some way. Taking bits and pieces and trying to assemble them into a coherent, or seemingly coherent, whole.

But isn’t there a fear that you might not like what you put together at the end? Maybe there’s a resistance built into completing it.

Maybe so.

Certainly in Eric’s case—this is a story you don’t actually want to be confirmed in a way. I mean, I don’t.

Do you?

I don’t mean his knowing the fate of his father—but the fact that this happened. It’s hard to want this sort of thing to be confirmed as real.

Yeah… How do you go about making sense of the world? And there’s a frustration as a detective. Detectives do want closure. I know I want closure. And there’s another problem: the desire for closure is so strong, so powerful, so pervasive, that sometimes you cheat. You take as fact something that isn’t fact, you confabulate, you confuse yourself in the process of investigating a crime. And to be constantly on guard against that sort of thing. Do I really know X, or is it just that I want to believe X?

The stakes are high for Eric because it’s his own story. But if you’re an investigator, you’re pursuing someone else’s story…

Well, even when you’re pursuing someone else’s story, what you’re investigating becomes your story too. You take it personally. Maybe not quite as personally as if it happened to you directly, but you take it personally.

So for this one, you must have been hoping that you would find the final piece—say, that Sy Hersh interview that gives you that final piece.

There’s also this knowledge that as you’re investigating, people are at the same time deliberately obfuscating. They’re destroying evidence, they’re creating false stories, they’re pointing you in the wrong direction. It’s amazing that we know anything. That’s what’s amazing—not amazing that we fail to find things out, amazing that we find anything out. People at cross purposes with each other, people who have the tendency to believe whatever they want to believe, a world filled with the credulous and the uncritical.

Wormwood

It feels like an especially fragile moment for that.

I would say a particularly despairing, fragile moment for that. I like the end of the movie too [in which a hotel maid is vacuuming a hallway]. Because that woman sat around all day waiting for me because we were trying to finish another scene, but she was there, ready to vacuum the hallway, at the very end. And I like it. I like seeing her vacuum to oblivion.

I love that shot. All this stuff was happening, and she’s dutifully doing her job. And then there’s the technical idea of “the clean room,” you can only deal with the evidence in the room?

Yes.

There’s also the idea that it’s never going to be clean. To go back to Macbeth, you’ll never get the spot out. Something happened in that hotel room no matter what. I thought of Wormwood as showing a kind of an original sin of the government.

I don’t think that’s so far-fetched.

It’s a very strange moment for the United States in the ’50s, fighting and vanquishing the ultimate evil, still our benchmark for defining evil, in World War II—and then five to 10 years later, this stuff is happening, at home.

You know, when the Soviet Union fell, people were worried, the John Birch Society thought, “Well, what will we do?” They don’t have evil incarnate anymore. The commies are dead, or at least they’re in retreat. And God in his great wisdom created Islamophobia, and that’s what the John Birch Society did, they just shifted gears. The new commies came from Islam. We’re always able to find evil somewhere, even if we have to manufacture it ourselves.

We do it in-house.

In-house evil.

Speaking about credits, the opening sequence, is it playing off the Mad Men opening credits? A man falling through space…

There was a worry about it, but it’s not playing against it. There is an element of the story that involves defenestration. You might say it’s contrived in Mad Men, but it’s not contrived here. This is an honest-to-God, real element in the story. Frank Olson either defenestrates himself or is defenestrated from the window at the Statler.

I love that Schrödinger description.

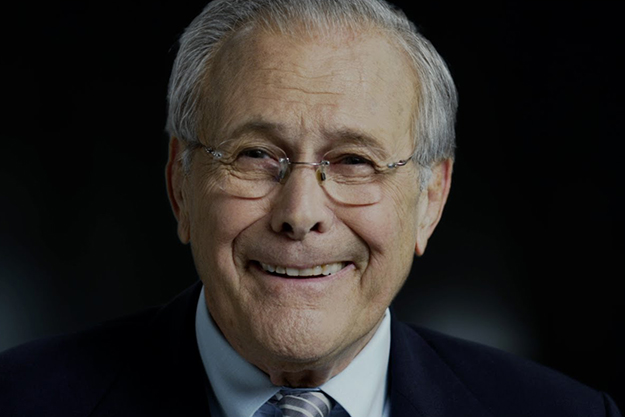

Very early on, I become aware of the Colby papers. The Colby papers are all these papers that are given to the Olson family by William Colby [head of the CIA]. They meet with Gerald Ford in the Oval Office and Gerald Ford in turn, aided and abetted by his loyal lieutenants Richard Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld—

The A Team.

The A Team. They ask Colby to give the family these documents, and a pile of documents is produced. They go to Langley, they see the “burn bowls.” And the documents are so strange.

So you’ve been through them.

Endlessly. Of course.

How do you go through an enormous pile of documents like that?

The first thing you do is you read them. You think about them, you read them again. They’re the basis of the script—that script comes out of the Colby documents.

How about that line about Frank Olson—it could be in a film noir: “Well, he’s gone.”

That comes from the Colby documents.

Who said that?

I believe it’s Lashbrook quoting Dr. Abramson.

Wormwood

So you read that, and you were like, “I’ll take that.”

Yeah. The Colby documents are a kind of script. That’s what’s so interesting about them, that someone scripted a version of what happened to Frank Olson that may be pure fiction. And in fact it’s talked about in the story. Eric at one point says that he doesn’t even want to think about the Colby documents because he’s decided that they’re really just some kind of smokescreen created by the CIA in order to deflect people from the role that they played in killing his father. It’s an epistemologist’s nightmare. That’s another reason why I love it.

It made me think of that image in The Unknown Known: a blizzard of papers, an ocean.

Maybe this is my insane fascination with documents, but I wasn’t sure: do I really want to make my companion piece to The Fog of War? Do I really want to interview Donald Rumsfeld? Do I really want to spend that much time with Donald Rumsfeld? And what really interested me, I think this is one of the strengths and one of the weaknesses of this project, is that I became aware of these “snowflakes.” I guess in the Ford administration they were called “yellow petals,” in the Bush administration they were called snowflakes because Rumsfeld produced this paper tsunami, essentially. He would just memorialize everything. And what meaning do these papers have, if any? Well, they mean something, but what? What do they mean? I think I once compared it to a squid producing this trail of opaque ink. It goes back to a question you asked me before, does Rumsfeld know he’s lying? Think of him as a falsehood generator.

He’s like Maxwell’s demon but with lies.

There you go. Although Maxwell’s demon is bringing order to the universe, attacking the second law of thermodynamics—whereas here, he’s aiding and abetting it. So let’s call him the reverse of Maxwell’s Demon. Is he even aware or is he lost in his sea of confabulation and words, misdirection? To call it lying makes it simple. Lying is simple, in a way. When you say lying, you know what the truth is, presumably, and you’ve just made a decision, I’m going to tell someone something that is untrue. But there’s a really messy world out there of endless prevarication—I love all the words for lying too, by the way: tergiversation, prevarication, rat-faced lying, and it goes on and on and on and on. Do we even know when we’re lying? Is it some kind of weird performance? One of the things that endlessly fascinated me about Rumsfeld, I’m asking the question again, does he really have an understanding of what he’s saying? Is it just some kind of weird performance art?

The most expensive piece of performance art ever.

Yeah, the Iraq War…

Just all an art project.

In finishing this new book for U. Chicago Press, I was always bothered by the absence of evidence as an evidence of absence, and I made an attempt to track it down as a concept.

You found Rumsfeld had intellectual antecedents?

Oh, yes. Respectable intellectual antecedents. And I don’t want to go into a lot of detail about it. But just recently, I was reading Bertrand Russell’s obituary for Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Where did he write that for?

I think it had been written for Mind. But you can easily find it and it’s very funny, Russell asking this question whether Wittgenstein was a genius or a fool and describing this argument he had had with Wittgenstein about whether there was a hippopotamus in the lecture hall. And Russell said that he felt he could, with some degree of conviction, assert that there was no hippopotamus in the lecture hall. No hippopotamus. Wittgenstein seemed skeptical. So Russell went around the lecture hall looking for the hippopotamus and said, “There’s no hippopotamus in the lecture hall. Period.” Wittgenstein was unconvinced. So the concept actually came from Carl Sagan.

Really? Good old Carl Sagan.

Blame Carl Sagan for the Iraq War, okay? It was started by Carl Sagan, amplified by Martin Rees, the astronomer royale, master of Kings College, Cambridge. I never knew Carl Sagan, I do know Martin Rees. So I had a conversation with Martin Rees. I said I don’t feel comfortable with this concept. It works really, really well when you’re talking about the universe. The universe, correct me if I’m wrong, is considered to be a big place. It’s a house with many rooms. So if I say to you, I haven’t really detected any evidence of extraterrestrial intelligent beings and you say, well, you know, the universe is a big place, nooks and crannies, it’s like Thomas’s English Muffins, you don’t know all the stuff—the nooks and crannies argument. Maybe you just haven’t looked in all the places you might look. So, absence of evidence is perhaps not evidence of absence. So I said to Martin Rees, you know, this works for the universe as a whole—maybe. I don’t actually believe it does, but let’s just say it does. Let’s imagine your bedroom, smaller area, and go back to the Wittgenstein argument. You say, I can’t find any evidence of a hippopotamus in my bedroom. And I say to you, absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence. You say to me, hey, go fuck yourself. I looked in the closet. I looked under the bed. I looked in various drawers, in your dressing cabinet. And there’s no hippopotamus. There’s no hippopotamus. So the absence of evidence of this hippopotamus is evidence of absence. Wise up! The way I sometimes describe it, is Iraq closer to the size of your bedroom or to the universe? And I would respectfully submit that it’s a lot closer to your bedroom than it is to the universe.

Rumsfeld struck me as just deeply delusional, self-satisfied, clueless. He’s one of the scariest… People would criticize the movie because he wasn’t like McNamara, because he didn’t feel guilt or didn’t have—I mean, I think you’re missing the point.

The sad thing, though, is that a person like that is ostensibly or outwardly content because they have no illusions. But then someone like Eric is tormented because he is trying to find some coordinates to history.

Maybe it has something to do with tragedy. I remember thinking years and years ago, if you put Hamlet in Othello and Othello in Hamlet, would there still be a tragedy? Othello wouldn’t have wasted time with Claudius—he’d just fucking kill him. He’d say, “Fuck you, Claudius, you’re a dead man.”

The Unknown Known

He’s a man of action.

He’s a man of action. Would Hamlet have killed Desdemona? Probably not. He probably would say, “You know, should I kill her? Oh, I don’t know.”

“Do I really know?”

“Do I really know? What is the real evidence? It’s just a stupid strawberry handkerchief. It could’ve come from anywhere.” Here you have a character who is really Hamlet-like, epistemically, to sound highfalutin, but tortured by evidence, tortured by the nature of the world around him.

There’s also this weird sense by the end that Eric’s been lapped by history in some way. He kind of even looks the same for the past 25 years. The world has gone on, and he’s still trying to establish this one thing. So that’s another facet to the tragedy. History goes on, but it’s not like he has a stable story.

I think that’s true of history in general. What interests me is not losing history. Part of history is the reconstruction of history, of trying to sort of figure out what history and how we know about it and what it means and what its significance is. And I like to think that Wormwood is a story about looking at history, and trying to figure out what it means. Ultimately, what it means for Eric, but [also] what it means for us. And I want to do some more of these, God willing. If I’m really polite and apologize frequently, I’ll get to do some more of these.

It all feels plugged into the moment we’re in right now, with Charlottesville and everything else, where history repeats itself in terrible ways.

And at the risk of sounding even more pretentious than I sound already: I have a version of Santayana quote, “Those who are unfamiliar with the past are condemned to repeat it.” The Errol Morris version is “Those who are unfamiliar with the past are condemned to repeat it without a sense of ironic futility.”

Sounds about right.

We just all hope and pray that this comes to some non-horrific conclusion. It’s a bad time. It just seems like a colossal mistake.