Interview: Deborah Stratman

The latest feature by Chicago-based experimental film stalwart Deborah Stratman, The Illinois Parables, is a kind of avant-documentary epic that, in the course of an hour, covers a couple of millennia of human history in the state. This is distilled down to 11 chapters, touching on such disparate matters as the Trail of Tears crossing the Mississippi River, the burning of the Mormon temple at Nauvoo, the apocalyptic Tri-State tornado of 1925, and the mysterious 1948 case of the so-called “Macomb Poltergeist,” involving a teenaged girl named Wanet McNeil who some believed was responsible for starting a string of house fires through pure force of mental energy.

Last month, Stratman was in New York to present The Illinois Parables—which just began a week-long run at Anthology Film Archives—as part of Projections in the New York Film Festival. She sat down with Film Comment to give a master class in the known and not-so-well-known history of the Land of Lincoln.

What was the gestation process of The Illinois Parables and how did it start to take shape? I’m interested in how you determined the in and out points of your timeline. For example, the last section is tagged 1985.

Because that’s the year Michael Heizer finished Effigy Tumuli, his land-art sculpture, which I think is his only representational land work. The area had been used for coal mining, and that had been done I don’t know how long ago, when he reclaimed it. I ended up settling on organizing things chronologically, I tried a bunch of different other orders and none of them… they would work really good for the first half but then the second half would fall apart, or vice versa. And so we end in ’85, because, of the stories I distilled it down to, that just happened to be the most recent one.

When you first set out to start shooting did you even have the idea of the general framework in mind?

I had the general framework in mind a few years before I was done, but not at all that it would be chronological, and definitely not that it was gonna end with Heizer. I knew there were going to be mounds in the film, and then I was excited that there could be these three kind of mounds, and each one kind of masquerades as what the last one was. So I like that you in the very beginning you see all the three types, which is a Cahokian, first nations mounds, 600 CE.

I found the mounds really, really early on, and I met that guy, Ravenwolf, who kind of walks into the frame by accident, really early on. It was literally probably one of the first shoots I was on for the film, when I didn’t know what it was at all, I was on a different trajectory. I knew from the get-go that mounds would be in there, because I like that they’re story-telling, they’re inscriptions, they hold a history of a place, and a really specific one that some culture has written, and they aren’t language-based. That seemed important to me. And I’ve used cairns before in films, not that those are cairns exactly, but this kind of land form that leads you through or that rhymes. But it wasn’t until quite a bit later when I was just camping, and saw the sculpture in Illinois, which I thought was shocking. It was neither here nor there to me that it happened to be representational, but I liked that he was appropriating this prior farm, putting on the jacket of some previous version of a myth, or a version of a culture. It’s not exactly masquerade, but it is, kind of. I feel like that happens a bunch in the movie: some story sees a relevant story that happened before and kind of has affinities with that.

In terms of the vignettes that make up the film, what was the process of winnowing them down, how did you get down to 11 chapters?

It was somewhat torturous. It’s not like I had hundreds of possible myths. I did have other ones, though, that I thought might work. Like for a long time I thought I would work with Studs Terkel somehow, because he is like this very important figure to me in Chicago. He’s a genius, I think, at getting other people to tell stories, and I felt like, “Oh, that could be really relevant with all the other stories that are being told,” and for a while I thought, Harold Washington might be in there, but then I thought I didn’t want it to be too Chicago-heavy…

Which it’s not at all.

No, I don’t think it is in the end. I guess I wanted each of the places to be not a “thin” place in the sense that the Jesuits think about a thin place, which is for them a place where the border [blurs] between the phenomenal, real, lived world and the after world. I don’t know if you’d consider it to be paranormal, I think it’s more the afterlife—the border between what we trust, logically, and real life, and something other, maybe a spiritual world or the life of the dead. And then I thought I really like that idea, but transposing this to a more secular place. So it’s a thin place but the membrane is between our world and some loaded past, that’s heavy or maybe politically fraught in some other way. In terms of natural forces, something heavy, or a heavy history there. To me the membrane felt thin.

And then I knew I wanted to have them do something with belief, or with people faced with something, like a conundrum that they can’t solve, so they reach towards faith, or they reach towards technology—they’re not exactly the same thing, but it’s the same amount of reaching. But there also was a lot of groping and not knowing, maybe having a few chapters of something and feeling… that something was missing.

In the early chapters you’re making these pilgrimages, going to these places to see what kind of residue is there, and I thought a lot about the Straubs in these sections. But your approach isn’t schematic in the slightest. As you move forward chronologically you do many different things, in part because there are different sorts of physical evidence that make themselves available to you. You have archival recordings in the 20th century, so you hear the voice of Fred Hampton, whereas you can’t hear Joseph Smith, and so on and so forth. That’s one of the things that I found beguiling about the whole enterprise, is that you didn’t just find your single tactic and then feed everything through it’ you’re constantly rethinking and reevaluating.

Yeah, and to some degree I know that there was a shifting of tactic in part because the production took a long time. Maybe I was more interested in what reenactment could do later on than I was when I was really first shooting… but on the other hand, I felt like I was naturally finding figures who were reenacting. The fact that Ravenwolf [who appears to be African-American] comes into the frame… He may well have Cherokee blood, or First Nations blood, but he’s really enacting a role on his own. Deciding that that’s going to be a version of culture, or a version of history, or some version of self that he’s going to wear. So even if I wasn’t as active in employing enactment, I was thinking about it from the beginning, or more just seizing on it when it showed up. I certainly didn’t know in the beginning that it was going to accrue as many different kinds of telling as it does. It’s just freaking every kind that there is. There’s paintings, and there’s voiceover, and there’s intertitles, illustrations and maps and landscapes. And then you have a physicist who works at University of Chicago, playing a physicist who used to work at University of Chicago. You have all these different modes of role-playing.

Or the almost Brechtian soundstage set up for the FBI re-enactment of the Hampton shooting.

Right. That I set up. That they set up. I got really into that as the film went on, how important it was to ritualize through enactment our reenactment. I hope the whole film asks people to keep taking back history, or to not let one version of it just sit, not that something like my film is going to be the end all. But it’s an encouragement to revisit these story, especially the Ed Hanrahan CBS footage that they shot at the state’s attorney’s office. The second I saw that in Chicago Film Group’s film The Murder of Fred Hampton, they had used clips from it, and I had looked for the original, and I might have used the original at one stage, but we just couldn’t find it. And then I thought, “You know, it’s actually much closer to my project to freaking rebuild the whole thing,” and have people playing those people, and let their gestures both illustrate the original intent of the reenactment, which was to re-intentionalize the act, and then to let them also speak for some of the Panthers, to let their gestures serve another master, I guess.

One artifact that I could not identify the provenance of is the audio of the tornado, where the guy is describing a tornado tearing up all the “Freakin’ houses” outside. Where on earth is that from?

It’s from Washington, Illinois—it’s off of YouTube. I came across it somewhat accidentally. I was in a meeting with one of my grad students, who was from southern Indiana, actually, but was collecting different tornado footage for something. I can’t remember. He was showing me clips, and I was like, “Wait, wait, wait! Stop, stop. Where in Illinois is that?” The audio just blew me away. So I knew right away I wanted to use it. I had already had it for quite some time, the aerial footage of the Tri-State Tornado, which is still to this day the biggest tornado that’s ever hit the contiguous U.S. A mile-wide thing going through three states. It’s quite a major act of erasure.

I knew that I wanted to have three really distinct registers in the film—temporal registers, but also emotional registers. Because [before the tornado sound] you’ve been in that realm where all these people who lived in Murphysboro are telling a story. And I love how their voices are coated in growing up in that place, growing up in Central Illinois, they have a certain idiom. But you feel a type of specificity, and there’s a politic to that, I guess, that I really loved. Then you hear the song which has something of religion in it, or sort of pleading. “Sweet Hour of Prayer”—like, shit, who do you turn to? So that had an emotional, faith-based register, and then I wanted to include more of a municipal, state, governmental response to erasure. Not like a machine exactly, but a federalized, machine-like response. And then the Washington tornado on YouTube. I feel like sound puts you in a present the way that images never can, because there’s no such thing as representation in sound. Whereas if you look at a still image, or an old film image, you recognize right away, “Oh, that’s from that time.”

I don’t think “freakin’” was popular parlance in 1925.

Freakin’! That’s right. I liked layering, making those sound lasagnas like that, where multiple temporal registers and emotional registers and panic registers can happen in a way you can’t do visually. You can superimpose images, but it never has the clarity that sound does. Sound lets you stack geological layers, and you can still make meaning out of it, instead of just a mush.

To talk about visual lasagna, you do a bit of that as well. Or at least we have these overlays of documentation onto the land that the documentation is dealing with in the Trail of Tears chapter.

That’s true. You see the act, President Jackson’s act, superimposed on top of the snow. But there’s not a lot of text on top of image, actually. Most of the text titles are just on their own. Maybe you’re talking about other lasagna.

And there are other documents as well, we have the articles of incorporation for Nauvoo, is it?

That’s right. Those are from Étienne Cabet, who was the founder of the Icarians and the French socialists, they were from the frontispiece of his book, like, “A Voyage to Icaria.” So they’re taken from that. And they’re on their own, they’re not on top of anything else. I’m definitely employing murals that are in places, or historical plaques that are labels that are like poking a hole, leading you into a place —if the sign or the mural wasn’t there, you’d have to be in the know.

You mentioned the production as being made up of a lot of these pilgrimages, and the movie has a very solitary feeling—one has the sense it’s kind of just you and a camera.

You didn’t sense my crew of 20? [Laughs]

What is the actual experience for you on these trips? This is something that I’m always very preoccupied with, that impermeable boundary between the place and the history. I very much am somebody that enjoys going on these pilgrimages, but I always run up against a brick wall with them.

They don’t open up to you?

They don’t open up. Though I take these kind of trips compulsively.

I mean, it’s not like every time I go to them that they do either. Ultimately they open up in the cinema more than anything, but there were times with the mounds especially, or at the river… Certain places do move me. I’m not necessarily feeling the particular history I’m trying to poke at, but sometimes I find something else there that does transport me. Like when I was shooting around Nauvoo, and the mayflies were going crazy by that go-kart track, you just see this swarm, like this ghost cloud of mayflies. That totally pierces through for me, even though I wasn’t like, “I sure do hope there’s gonna be a swarm of mayflies down in Nauvoo.” So sometimes it’s just going to the place, and it’s the oblique thing that catches you by surprise. Or, a lot of the snowy shots near the Mississippi and near the Illinois River. I get really moved by that, but it’s not that that’s like peeling the lid off the can of Trail of Tears, necessarily.

Some things just happened so by accident. I went to film the Mormon temple at Nauvoo, and then years later was looking for some kind of paintings, because I knew I wanted more two-dimensional stuff, and then found Carl Christian Anton Christensen’s painting of the temple on fire, which weirdly was from just exactly the same perspective! That was something I had shot four years ago. You just go, “Oh my God! That’s freaky.” They’re the same scale and everything. “I guess I don’t have to go back and shoot it, because I already have exactly the right shot.” So sometimes it’s just finding a frame, that obviously some other artist had also found, then it’s just kind of a geometry of place that you accidentally stumble your way into.

Outside of these bits of serendipity where things really lined up, were there any things that you wanted to see in the movie that just, for whatever reason, didn’t find a place?

For a long time, I had wanted giant corn piles, of ethanol plants, the mounds, I wanted that to be one of the mounds in the film. I had a lot of shots around refineries too. Those industrial uses of the land were important to me, but in the end, it felt kind like they felt definitely of technology, and they were solving problems, but somehow they didn’t fit in.

I kept doing other films in the interim, because it felt too unmanageable to try to get at something about belief, or morality. I still can’t talk about it. I still feel like I don’t have a language for it. It’s been out touring around for like seven months, I’ve really got to find my two-sentence gem. I do not have an elevator pitch. That’s part of my problem. Finally, I knew I wanted to fly up above the Heizer; that took forever to arrange a hot air balloon, because the drone felt totally wrong, this mechanized thing. I wanted it to feel really bodily, and handheld, because everything else is so static. It’s really a pretty static film.

And it’s very different from a helicopter shot, were you would always see the grass and trees thrashing around.

And you’re just kind of like dragged to the side and, like, “What?” To me, it still kind of gives me that goosebumps, but you feel your body lifting in a way that I don’t think you would if you felt the mechanism of a helicopter or a drone or something more stable, where you feel a machine lifting your body, that ascension… I needed a relief, because the stories, they’re kind of depressing, and they’re unconsciously adding up. You’ve sat through a lot of kind of grim tales by the time you get there.

The episode that comes shortly before the Murphysboro tornado is something that I was wholly unfamiliar with, where you’re looking at this rash of house fires, which are represented as being possible acts of pyrokinesis, as seen in a sort of Carrie-esque re-enactment with a teenaged girl firestarter.

Yeah, she’s my little Carrie. She’s one of the parables that I had at the very, very beginning. I was fascinated by her story, because it came right on the heels of that critical mass equation [at the University of Chicago], and realizing, “Oh, we have God-like powers to wipe out the planet.” It was less than a decade later, so you knew that story was the American subconscious, suddenly having this line on destructive, anthropic power beyond what we had ever quite had a line on before. So that was really fascinating to me, because I felt like the fact that all the newspapers were talking about this, that the military was called in, that they felt like “This might be radioactivity,” that all that speculation was really coming out of the temperature of the time, the military-industrial temperature of the time.

But more importantly, I just liked that there could be, not just a female figure, but this preteen girl who somehow asks you to reckon with the forces preteen girls can unleash. Maybe it’s not like, “Oh, she’s actually telekinetic and can burn shit down.” But I feel like it’s not far off from the emotional turmoil, and just the power that young women have. It’s not like I wanted to directly say, “Oh yeah, Fermi, well, check this out. This 14-year-old girl can burn shit down too.” But I wanted some kind of emotional rejoinder. “Emotional” isn’t quite the right word. To be able to believe in the more invisible, humble force of a population that’s usually not looked at as being incredibly powerful, but maybe is subversively so. I wanted her to be the badass of the film on some level.

Another one of the incipient forces bubbling under the surface throughout.

I’m a fan of the paranormal on some level.

It’s your Time-Life Books Mysteries of the Unknown moment?

Yeah. I’ve always been interested in where logic butts up against the metaphysical, because I’m kind of fascinated by both, intrigued by both, have a certain level of belief in both.

You embrace the baroque paradox.

Yeah. I like a little bit of poetry in my science. I like when they butt up against each other. That was a real early sequence, her burning down the house. I mean, she went later, and they were like, “Well, turned out she was just a pyro and really quick with matches…” But so many newspaper accounts were just like, “We’re having it.”—that this girl was telekinetic more or less, or that she somehow had harnessed some kind of forces beyond anybody’s ability to reckon with.

It’s just a really lovely movie, in terms of getting down the discreet charm of the Midwest. You’ve got the gray-green-browns, and the low thrum of depression rumbling through the whole thing, mild seasonal affect depression.

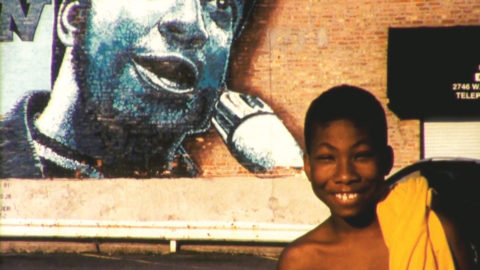

Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, corn. You forget about “hay dude.” He’s smiling. Remember, there’s that guy. Actually, you can’t see the hay dude sign, just “Ha.” So maybe it ends up being depressing. I just had the wrong freakin’ lens on. But he looks so resolutely happy to me anyway.

One of a menagerie of creatures. Between the Piasa bird and the temple at Nauvoo there are a lot of torches being wielded in Illinois, apparently.

There’s some stuff on fire. There’s a lot packed in there. I can’t even remember what’s in my own movie. Sometimes, I’m watching it, and I’m like, “Oh, yeah!”

But that’s part of the pleasure of it. It’s so full.

It’s pretty dense.

And that’s wonderful.

Maximalist minimalism, that’s what I go for. That’s going to be part of my two-sentence pitch.

Maximalist minimalism is good. You’ve had multiple career retrospectives going around this year, how are you just now getting “maximalist minimalism”? That should have been the title. You’re leaving money on the table.

Thanks! I don’t know. I have a hard time arriving at a succinct… I don’t think it’s a succinct film. It’s kind of messy. People are always asking, “What do you want people to learn from the parables?” I don’t know. That’s where you guys come in. I don’t really know what I’m trying to learn from them.

That’s another really interesting aspect of the film. That tightrope between the didactic and oblique, the information you give and the information you withhold…

That’s true. It’s a specific, multi-tiered course, for sure. Like, “Here’s your three peas now. Here’s your little bit of Chardonnay.” It’s not that I want to come away with people knowing, “Okay, this film is about tolerance.” Or, “This film is about exodus.” Or, “This film is about xenophobia.” Or migration. But I want all of those things to exist as what bubbles to the top. I hope those things are in there, but I don’t necessarily feel like someone’s going to come away, like, “I learned that lesson! Next parable!”

I’m glad you brought up the Straubs, because I love Straub-Huillet, and I don’t think this film is an homage to them or anything, but there were lessons learned for sure, when I first saw Fortini/Cani, From the Clouds to the Resistance. Just the way they would have such specificity of what they were going to share with you—oblique but at the same time generous. I feel like I’m probably a bit more generous, actually. I’m not brave enough to be as oblique as they are.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.