Higher Learning: Anne Charlotte Robertson’s Five Year Diary

Higher Learning is a regular feature at Film Comment in which campus-based scholars share concise essays, bringing our readers into the rich and varied conversations occurring in the fields of film and moving-image studies.

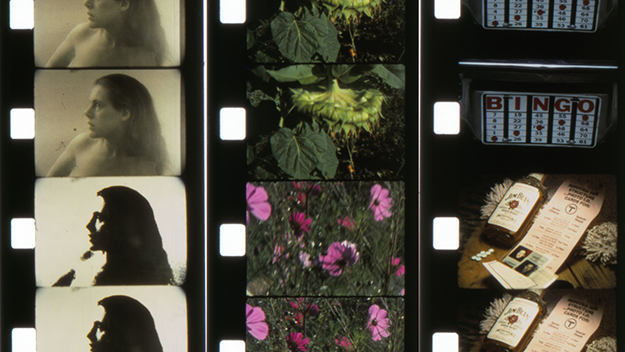

Film strips from Five Year Diary (Anne Charlotte Robertson, 1981–1997)

Against a dark background, Anne Charlotte Robertson faces the camera. Light comes through the window and catches the left side of her face. She is a filmmaker, a gardener. She is 45-years-old, single, childless. “I shall try to imagine being happy,” she says, “I shall hope for miracles.” From the soundtrack’s left channel, she speaks over herself, doubling the voiceover: “You can see my face is rather stiff. My mouth is making movements. It means I’m taking the anti-psychotic medication.”

The sequence is from Reel 80 of an autobiographical film project which Robertson started in 1981. But her Five Year Diary continued far longer than its title anticipated. At over 38 hours spread over 83 Super-8 reels, the film documents Robertson’s life across 16 years. She finally ended the project in 1997, though she lived for 15 more years. The Diary chronicles Robertson’s loving dedication to gardening and filmmaking; her frequent lapses into states of mania and anxiety. Much of it is shot in her vegetable and flower garden, in the kitchen where she cooked, pickled garden produce, recorded voiceovers, wrote scripts, letters, diary entries, and poems. It also chronicles her art education at Massachusetts College of Art, where she was taught by Saul Levine, as well as trips to Walden Pond and other gardens.

Robertson filmed Reel 80 in the spring and summer of 1994, largely at the house she shared with her mother in Framingham, Massachusetts. In this reel she mourns the death of her three-year-old niece Emily. She films a medical center’s window signage. Here she was hospitalized after Emily’s death. She cuts to a street sign: “Watch your step.” Then the palm of her right hand. It is full of pills—Valium and Risperdal. And now another cut. She is in the garden’s amber light. It is the early evening. She says, “We go to the garden, we go to the garden, we grow in the garden.” Surely the ambiguity of her utterance is deliberate: to grow one’s garden and to grow one’s self. In Robertson’s mind, these efforts go hand in hand. In her 1994 short film Melon Patches, or Reasons to Go on Living, Valium transmutes into watermelon seeds in Robertson’s outstretched palm. Through this gesture Robertson exchanges medication for home-grown respite. In Five Year Diary, Robertson’s garden is a refuge delivering solace in self-therapy. “I had no children,” she says. “All I had was a garden with seeds.”

Reel 80, Five Year Diary

As the years passed Robertson grew increasingly anxious about her failure to find a husband, which she attributed to a loss of beauty through aging. In Reel 1, she films a squash on which she has painted eyes and a mouth. The same squash lies in the compost seconds later, rotten. A similar scene of decay is poignantly rendered in Robertson’s 1985 short film Rotting Pumpkin. Here she paints a woman’s face on a pumpkin whose decomposition is documented in time-lapse over several weeks. The film is a self-portrait, the pumpkin its memento mori. Robertson was at that point only 36. But already we witness panic at her ageing, manic episodes, and loneliness. In Reel 23, she drives through Boston and catalogues her landscape in a frenetic voiceover:

This is called mania. Everything has significance. Everything is heightened. Everything is wonderful. I will fall in love with a guy. I will see the man I love somewhere around. Maybe he is like a lion. No. He is like an eagle. He is like a Mazda. No. He is 83. He will be 83 years old when… It’s 2:42 somewhere. Really, it all had significance. And he would put it together. Later on. When I found him.

In the garden too, everything has significance for Robertson and her camera. She films heads of roses, sunflowers and marigolds in frontal close-ups—as one might film a face. She frequently refers to flowers as her own children. She often films the moon, uses it like a clock face to measure the passage of time as well as changes in her mood. She synchronizes the planting of seeds to lunar phases. Through this conception of gardens as vibrant fields full of interacting forces, Robertson’s films show a keen perception of the myriad agencies palpable in the natural world. She anticipates current ecological theory that contextualizes human existence within a larger system of non-human elements.

Reel 23, Five Year Diary

So too Robertson challenges us to redefine our conception of diary and autobiographical genres. Her work is striking because it allows us to emphasize the inherent communality of autobiographical filmmaking which is often obscured by its denotations of individuality. Her autobiography includes not only interpersonal relationships, but a network of interactions with plants, animals, and weather. Robertson was certainly influenced by the 1970s turn toward personal filmmaking and, more broadly, the decade’s redoubled emphasis on self-exploration. However, her films enrich this movement by opening up the autobiographical self to the multiplicities of the natural world. Her films explore subjectivity and subjecthood as they relate to wider, non-human elements, thus differentiating Robertson from more self-absorbed or family-oriented diary filmmakers such as Robert Huot and Ed Pincus. Although feminist and psychoanalytic frameworks may be applied to Robertson’s Diary and link it to the work of Schneemann or Brakhage, her work can be read as a filmic continuation of New England’s ecocritical literary legacy. Robertson’s interest in writing, which fed into her idiosyncratic voiceovers and a substantial paper archive, suggests an affinity with Emily Dickinson’s journals. Her dedication to local landscapes and nature invites consideration alongside Jewett and Thoreau. Her closest filmic peer is Marjorie Keller, whose interest in gardening and literature yielded her film The Answering Furrow (1985). Keller and her husband, P. Adams Sitney, were friends and champions of Robertson. Brakhage was another supporter of Robertson’s work.

In Reel 47, Robertson bids farewell to the autumnal foliage. The words ‘final’ and ‘last’ are repeated. Filmed at the end of that fifth year, the reel’s subtitle is I Thought the Film Would End. The Diary continued for 36 more reels. The final reel opens with an image of Robertson’s father and brother’s shared gravestone. Then there is a photo of Emily, a Christmas tree, fairy lights, gifts. Spring has arrived. Robertson’s hair has greyed, she is nearly 220 pounds. Still she has not married, and this threatens to overshadow the fact that Robertson has by now created a significant artistic work. Her tone is stoic, forlorn, jovial by turn. The Diary’s unceremonious ending perhaps points to potential reasons for Robertson’s inability to end her project after the five years which had initially been allotted to it. The film’s end ultimately mirrors the essence of gardening. Gardening does not end. Though vital, fallow periods are not indefinite. The season will inevitably change. There will always come a new time to prune, to plough, to plant.

Becca Voelcker is a PhD student in Film and Visual Studies at Harvard University, and a freelance film critic and programmer.