Film of the Week: Fassbinder: To Love Without Demands

Towards the end of Christian Braad Thomsen’s documentary Fassbinder: To Love Without Demands, Rainer Werner Fassbinder quotes Jean Genet: “To be complete, you have to double yourself.” Thomsen reads this as evidence of Fassbinder’s protean, contradictory nature: “You can’t say a thing about him,” says Thomsen, “without saying the opposite”—to wit, Fassbinder was sometimes a hooligan, but he was also a prince. Inevitably, this week, it’s another protean prince—the slimmer one from Minneapolis—who comes to mind when considering Fassbinder and his phenomenal output.

Both artists were men who not only doubled, but multiplied themselves many times over; whom you imagine must have had the gift of splitting themselves into many different selves, not only in order to have so many varied artistic voices, but to create relentlessly at work rates alien both to sleep and to normal human levels of stamina. Fassbinder, of course, died 20 years younger than the other—aged 37, after 40 feature-length films, two TV series, and assorted plays for stage and radio. Thomsen ends his account by mentioning a recurring dream he has had since the director’s death in 1982: in it, his old friend confesses that he is not really dead, just taking a well-deserved break, and can’t wait to get back to work.

Thomsen discovered Fassbinder in 1969, when his first feature Love Is Colder Than Death was booed at the Berlin Film Festival. As a Dane, born in 1940 when his country was invaded by Germany, Thomsen had grown up hating the German language, seeing it as profoundly unpoetic. Discovering Fassbinder’s films changed all that. Certainly, in the interviews seen and heard here, Fassbinder shows a rather idiosyncratic relationship, if not to German specifically, at least to language itself, or to everyday logic. He is heard talking about the age-old thriller equivalence between cops and gangsters, and says he prefers the latter: “They pay their own expenses, while policemen are insured and backed by unions.”

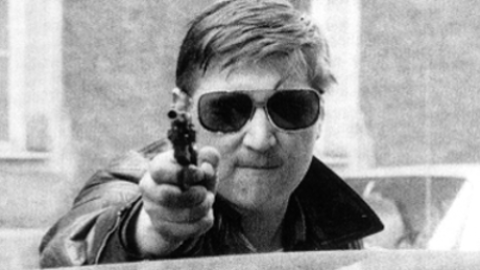

Thomsen’s film is at once an essay on Fassbinder and a personal reminiscence. It’s also an unevenly structured assemblage of material, including stills, odd film clips and archive material, and interviews—some with Fassbinder that Thomsen shot over several years, as well as more recent interviews with a small handful of associates. The most significant material is an interview with Fassbinder in Cannes in 1978, which Thomsen says he was previously reluctant to use because the director looks so much the worse for wear. Glass in hand, ice cubes clinking distractedly, a slurred Fassbinder—in rakish black shirt and grey waistcoat—philosophizes lugubriously, sometimes fancifully and sometimes very provocatively about various subjects, and talks about his own childhood in the years immediately after World War II. Entrusted to his grandmother and various members of an extended childhood, Fassbinder knew extraordinary liberty, but little structure—of a freedom which led to “a total sense of disorientation” but also to “an indestructible power of resistance.” He also speculates on his own restless productivity, for which the commonplace term “drive” is almost derisorily inadequate: “There must have been something compulsive… something I couldn’t control. That’s why I refer to being ill. I thought I only existed while working.” Later, it becomes clear why Fassbinder put so many of his lovers in his films, whether they were, properly speaking, actors or not: as he was always working, it was the only way he could spend time with them.

Thomsen’s own rueful German-language voiceover gets particularly creaky when he feels he needs to explain the Oedipus complex to us, yet that phenomenon clearly plays a very unusual part in Fassbinder’s relationship with his mother Lilo (Liselotte) Pempeit, whose voice is heard at various points. She was another object of affection that Fassbinder felt the need to film: she appeared in 24 of his works, one of her most prominent roles being the heroine’s mother in the 1974 adaptation of Fontane’s novel Effi Briest. Fassbinder himself is no slouch when it comes to oedipal speculation. Incest with his mother, he muses, “could certainly be a major experience in my imagination.” He adds: “I’m convinced that in reality it would be a catastrophe.” Even so, he feels that proper sexual relationships with one’s parents “would liberate people to have more beautiful possibilities” in their other relationships; incest “would equalize power relationships between kids and parents.” It’s hard to tell which Fassbinder is talking here, the provocateur, the ’70s radical libertarian, or the drunk (but why separate them out?). In any case, Thomsen seems to have been entirely on Fassbinder’s wavelength in the ’70s when it comes to talking his bizarre language of psychosexual relations: “I never raped my father and I didn’t kill my mother,” says Fassbinder. To which Thomsen replies, temporarily flummoxing his interviewee: “You turned her into an actress. That’s the same thing.”

Fassbinder isn’t the only one to speak with alarming frankness. Thomsen doesn’t have many interviewees on offer: we hear Margit Carstensen speaking in extraordinary silky tones about how the director radiated “so much love, kindness, and a sense of family” and “had very traditional ideas of what a family is” (well, perhaps not that traditional, as we’ve learned). Longtime associate and sometime actor Harry Baer appears on camera, filmed recently, offering some more dispassionate memories of the pleasures and problems of their collaboration. And while such key figures in the director’s intimate circle as Hanna Schygulla, Ingrid Caven, and Juliane Lorenz (the latter two both married to him at different points) are conspicuous by their absence, the most revealing presence here is that of Irm Hermann, a regular repertory member from the start, who lived with Fassbinder for a time. Thomsen rather overstretches her time on screen, using her interviewees in long uninterrupted chunks; as with the Cannes interview of Fassbinder, his reluctance to splice up footage in conventional documentary fashion makes for a clunky structure that sometimes drags.

Nevertheless, Hermann’s reminiscences are deeply unsettling. “Basically,” she says, “I was his possession and I was treated accordingly,” and compares their relationship with that of a pimp and a prostitute. When she talks of a suicide attempt following Fassbinder’s announcement that he was leaving because they had no more money, she does it in a thoroughly disarming “I can laugh about it now” manner. Her account suggests certain classic signs of abuse and acceptance: “If you’re the possession of someone,” she says, “you put up with a lot.” That acceptance seems to have been based on his giving her “enormous amount of attention . . . which no one else gave me. That made me aware of who I was.” It seems a Pygmalion syndrome, in which the director seems to have persuaded Hermann—plucked from her office job to become a star of his company—that he was essentially her creator. She eventually withdrew from the relationship after suffering brutal treatment while filming Berlin Alexanderplatz. She got out in one piece, but others weren’t so lucky; Armin Meier (a lover who acted in 1976’s Satan’s Brew and others) killed himself after failing to get an invitation to the director’s 33rd birthday.

One can only assume that the subtitle To Love Without Demands is intended with some grain of irony: Fassbinder comes across as someone who demanded everything of his circle, and it’s hard to say exactly what he gave back, apart from being the tender “family man” that Margit Carstensen speaks of. He certainly gave people a myth to cluster round, a flag to mark their own identity; perhaps the greatest international tribute to him is Greta, the world-weary Caven-esque character in Lisa Cholodenko’s High Art (98), constantly telling everyone that she was Fassbinder’s muse. By association, everyone who worked with him became irreducibly and forever “Fassbinderian.”

Thomsen’s is a confused, partial, awkwardly constructed tribute that is an interesting addition to the mass of commentary on Fassbinder, but hardly the ideal way in for non-initiates of a filmmaker whose reputation has more than once since his death seemed in danger of slipping off the canonical map. The film alludes to the contradictions in its subject’s life and work, although it doesn’t altogether engage with them, a little too in awe of his charisma and his unassuageable will-to-be-other. Not that Fassbinder was entirely aware of his own contradictions. Early on, he’s heard commenting on the Baader-Meinhof gang, paying tribute to their intelligence and sensitivity but claiming that their major flaw was simply impatience. “A revolution can take centuries. They only gave it decades.” But what was Fassbinder himself if not impatient? Whether or not he achieved revolution, or only managed to lay down proposals for future generations of dissenting filmmakers, he tried to do it all in only a decade and a half. That was his ruin—and his glory.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.