Film of the Week: The Wind

The expanses of the Old West can hardly have been a joyous place for anyone, but over the last couple of decades, several films have focused on showing how brutal the frontier was for women. Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff and the poignant Zoe Kazan showcase in the Coens’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs have shown women’s physical and spiritual endurance tested to the limit during the pioneer experience, while Tommy Lee Jones’s The Homesman showed women driven mad by that life. Emma Tammi’s intriguing debut feature The Wind takes these films’ insights into a psycho-Gothic direction, to tantalizing effect—tantalizing because the film so nearly hits a very distinctive note, but goes seriously out of tune in its attempts to combine genre elements from the Western and horror cinema. What we have here is a grim prairie tale, to echo the title of Wayne Coe’s 1990 portmanteau movie—not the first, but probably the most overt modern example of the hybrid cycle sometimes dubbed “Weird West.”

Tammi hits us at the start of The Wind with a striking image: a woman standing in front of a house holding a bundle, clearly a dead baby, with her dress soaked in red. It instantly makes us aware that, while we’re more than used to associating the Western with male blood, as soon as it’s a woman’s blood that’s at issue, whether menstrual or the blood of childbirth, the stakes—symbolic or gender-political—are entirely different

The narrative, zigzagging between present and flashbacked recent past, begins with a youngish couple, Lizzy Macklin (Caitlin Gerard) and her husband Isaac (Ashley Zukerman), living in a cabin in the middle of a vast plain at some point in the 1800s, and eking out a spare but ordered existence in isolation from all human activity. One day, new neighbors appear, the Harpers—Emma (Julia Goldani Telles) and her husband Gideon (Dylan McTee). The latter immediately marks himself as unlikeable when the couple come to dinner, turning a compliment about Lizzy’s cooking into a backhanded swipe at his wife; Isaac, meanwhile, scores plus points, albeit in an arguably anachronistic way for the 1800s, by getting dinner started rather than leaving it to Lizzy.

The Macklins are intrigued to have another nearby presence in this vastness: in one eloquent scene, Lizzy looks out into the night and sees the other couple’s cabin glowing some way across the darkness. “Is that what we look like to them?” she muses. “ A little flicker of light in the middle of nowhere?” Company is welcome, up to a point: “In cities, strangers stay strangers,” she comments. “Here we don’t have that luxury, do we?”

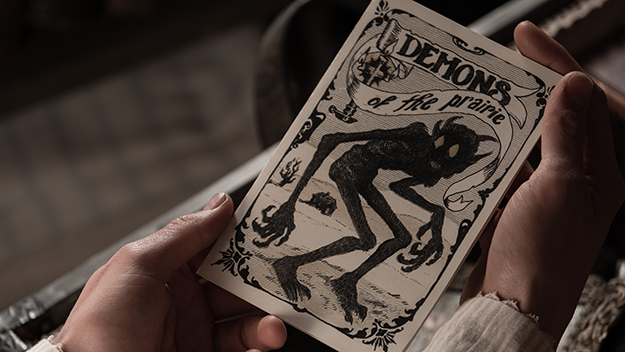

These two neatly turned observations about isolation and the equivocal benefits of proximity are among the more acute and subtle touches in Teresa Sutherland’s script, and in a film that sometimes wildly overstates its point. Why Lizzy is increasingly uneasy about her new female friend soon becomes apparent, as Emma seems to make a few too many complimentary comments about Isaac, and disparaging ones about her own man. There’s another danger in proximity. Emma, soon pregnant, is gripped by fears, possibly touched by some kind of madness, and there arises the suspicion that madness is contagious—psychologically, or through the effect of some strange prairie curse. There are, after all, those malign ancient presences listed in a pamphlet that both women are seen reading, entitled Demons of the Prairie.

Or maybe it’s not to do with the demons, just the reading. At one point, Lizzy entertains the ailing Emma by reading her a scary passage from The Mysteries of Udolpho, a hugely popular Gothic novel written in the 1790s by the English writer Ann Radcliffe. Emma, who already knows the book, reassures her friend that its apparent supernatural manifestations are actually produced by human intervention, in any early example of the fake haunting trope made famous by Patrick Hamilton’s play Gaslight (hence “gaslighting”). Ironically, though, Emma still finds herself prey to macabre fears about presences abroad astray on the plains, and before long those fears affect Lizzy too.

Yet The Wind never altogether successfully suggests that these fears might be born out of a combination of vast space and 19th-century reading habits. If the terrors that Lizzy later experiences are produced by her own mind, that would suggest that she’s an aficionado, not of the Gothic novel of Italian castles, but of late 20th-century horror cinema and eerie literature in an H.P. Lovecraft vein (when another character, who seems to have witnessed something, asks her, “What is that thing?” she replies, “I don’t know—it’s been here as long as we have”).

There’s no actual reference in The Wind to displaced Native American presence—which may lead genre adepts to think that the absence of any such reference is itself a sure implicit nod to horror cinema’s hoary “Indian burial ground” trope. However, the film offers its own engaging inversion of the notion of the great outdoors—like that great recent female horror film, Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook, this is a story in which the house, the supposed shelter from the terrors of the exterior, itself becomes a source of menace (in keeping with a trope established in the Gothic fiction of the late 18th and early 19th centuries). When Isaac has to take a ride away off yonder, Lizzy is left to face the terrors of the Great Interior—which may be her own mind.

Unfortunately, those terrors are awkwardly overstated: possibly phantasmal wolves nearly bashing Lizzy’s door down and goring a symbolically sacrificial white goat; lights flickering on and off, fires going out then bursting back to flame; even what looks like a hearty burst of plain old-fashioned poltergeist activity. Or is it just… the wind…?

Things really take a clumsy turn when a new character wanders onto this ominously deserted stage, clearly setting up a third act burst of the willies—which we get with full incongruous CGI and all, as the film overplays its hand as disastrously as Hereditary did in its closing stretch. Throughout, Tammi lays on too many sudden shock transitions and heavily signaled jumps on the soundtrack, intense crescendos and all (Ben Lovett’s score works best in its quieter moments, as in its touches of solitary, scrapy violin).

All that’s a pity, as the film is very eloquent when it just lets the simple images do their work: when Lizzy appears in a pale pink dress, we don’t know whether it’s actually that color, or whether it’s formerly a white one, dyed by blood leaked in the wash. There’s another very elegant shot (the DP is Lyn Moncrief) which has the Macklin house’s façade shot from below so that it looks horizontal, rhyming visually with a coffin we’ve just seen.

The film’s best special effect, in fact, is the coolly restrained performance of lead actress Caitlin Gerard, seen recently in Insidious: The Last Key. Her Lizzy, who is German-born, has a very Northern European brisk freshness to her in the flashback scenes, but looks increasingly severe and solemn as her troubles set in, with a definite touch of Joan Allen to the chilly set of her features.

The Wind doesn’t quite come off, but it suggests a visual imagination and a sense of economy from Tammi that you hope to see more of: it’s impressive how little it takes, in words and pictures, for the film to establish Lizzy as strong, Gideon as weak, Emma as troubled. What might have worked best—in a film that digs into both the old American landscape and the tropes of two genres—is the eerie, suggestive creepiness of, say, Robert Eggers’s The Witch, set two centuries earlier. In its quieter, sparer moments, however, The Wind begins to live up to the unstated obliqueness of its title.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.