Festivals: Il Cinema Ritrovato 2017

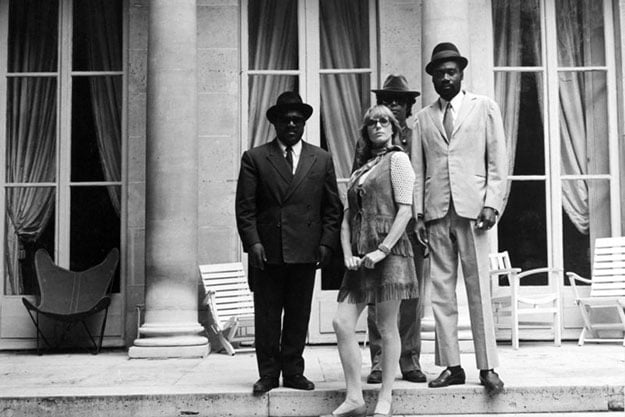

Soleil O

For a festival devoted to film history’s most towering monuments and deepest cuts alike, it’s curious that the 31st edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato would find itself plagued by that most contemporary of problems: the overabundance of choices of what to watch. Thanks to the generous efforts by the festival’s curators to present films as optimally and faithfully as possible, ICR attendees find themselves regretfully passing on a handful of one-of-a-kind items of interest for each screening they actually commit to catching. This stings a lot less when one accepts it as the fundamental reality of how we engage with movies today and resolves not to lose sleep over each rare print or new restoration missed; the experience of trying to plan out a week’s worth of screenings in a festival’s schedule isn’t a hugely different operation from that of combing Netflix, Amazon Prime, FilmStruck, etc. Even so, it’s tough.

Right out of the gate, word spread fast about the legendary Mauritanian filmmaker Med Hondo’s rousing introductions at the screenings in his mini-retrospective, featuring the Film Foundation’s new World Cinema Project restoration of his debut feature, Soleil O (1970). “A pure militant film,” as a French colleague described it to me, Soleil O follows a Mauritanian man (Robert Liensol) who heads to Paris, only to have an impossibly difficult time finding a job and escaping the resilience of the colonialist mentality. He encounters a succession of whites who range from incapable boors chosen over his more qualified (but black) peers for jobs, to a pair of horny bourgeoises curious about the mythical proportions of the black penis, to ostensibly well-meaning, supposed liberals who casually let slip their prejudices against immigrants from the “Third World.” Soleil O resembles a manifesto, scrappily shot across four years and suffused with a political indignation that, despite the film’s historical specificity, still feels urgent today. And, thankfully, the beautiful digital restoration neither excessively sands down the film’s low-budget edges nor otherwise slickens a work that sticks in the craw just as intended.

Even more audacious is Hondo’s Brechtian musical, West Indies (1979), set entirely on an aggressively artificial slave ship constructed within a Citroen factory in Paris. In what was the most expensive African production ever made, Hondo fleetly skips across the history of French colonialism in the West Indies, cycling an array of game actors (including Liensol) through a variety of roles within a centuries-long chronicle of conquest and oppression. But Hondo isn’t content to merely grind his axe: the satirical West Indies abounds with startling stylistic flourishes, occasionally suggesting what might have happened if Vincente Minnelli had steeped himself in postcolonialist literature and remade Godard’s formally kindred Tout va bien. In short, it’s a smart, angry, funny, and never less than lively work that almost renews one’s faith in art’s capacity to stir its audience to action. (And it certainly didn’t hurt that the film screened from a 35mm print whose rich colors handsomely underlined Hondo’s visual alternations between images of warmth and cold, blood and water, the bureaucrat and the slave laborer.)

Sarraounia

Hondo described his entrancing Sarraounia (1986) as being a more “classical” effort, which is true insofar as it adheres more faithfully to the strictures of conventional narrative than do the more explicitly radical interventions of Soleil O and West Indies. It concerns the escalating tensions between fin de siècle French colonialists (and their army of Sudanese mercenaries) and the titular sorceress, queen of the Azna tribe and trained from childhood to protect her people against all manner of encroachment. Hondo cuts between the clownish yet brutal developments on the French side of the equation and Sarraounia’s efforts to consolidate her influence among the neighboring tribes and prepare her followers for the struggle to come, capturing the dialectic between the hubris of the would-be imperialists and the more enlightened though no less political maneuverings among the would-be conquered peoples. Top it all off with Pierre Akendengue’s strong and quintessentially ’80s soundtrack contributions (the astonishing closing ballad finds an onscreen singer enumerating the many merits of including a bard in one’s squad), and the result is a work unmistakably concerned with the political dimension of style and narrative.

An altogether different tale of a woman making her way in the world of men was Max Ophüls’s seldom-screened Divine (1935), a kind of proto-Showgirls. Country bumpkin Ludivine (Simone Berriau) encounters a Parisian chorus girl visiting her village; the performer puts a seductive spell on Ludivine’s imagination, conjuring dreams of big-city success and showy glamour, before offering a slot on the chorus line. (This perhaps should’ve served as a red flag to our naïve protagonist, but the show must go on.) So it’s off to Paris, where Ludivine drops the “Lu” in her name and tastes both success and humiliation—an early scene where she learns that she’ll have to go topless in a performance anticipates Showgirls’ Crystal Connors waxing incredulous: “You expect me to go out there without a G?” Lo and behold, the theater in which (Lu)Divine now works seems to be a front for a shady, opium-related enterprise, and Ophüls’s mobile camera delights in gliding around and through the behind-the-scenes action, the all-too-predictable backstage backbiting now spiked with a delectable criminal element. Along the way there’s arson, an escape from Paris reminiscent of Jean Renoir’s The Crime of Monsieur Lange (1936) (which was released a year later than Divine and was also presented in Bologna, in a new digital restoration), and the redemptive love of a kindly milkman. Divine screened at ICR in a series spotlighting the film work of Colette, who penned its story and dialogue, and her script provides just the right amount of louche intrigue and somehow-chic ridiculousness for Ophüls to arrive at a film none will mistake for one of his best but is a masterfully crafted romp all the same.

The under-recognized German director Helmut Käutner also received an eight-film retrospective, which quickly proved one of the key happenings at this year’s festival. Each screening in the retrospective took place in the Sala Scorsese, which, while one of the festival’s only consistently air-conditioned theaters, was scarcely large enough to accommodate the surprising swell of demand for the postwar auteur’s work. And so, those of us who fell hard for Käutner cut our lunch breaks short each day to arrive at the theater 30-some minutes before showtime in the hopes of snagging a seat. I missed the first few titles in the retrospective, but finally had an opportunity to dive in with Ludwig II: Glanz und Ende eines Königs (1955), a fresh, Technicolor take on the Mad King that devotes the bulk of its first half to setting up a faintly homoerotic account of the push-pull rapport between Ludwig (O.W. Fischer) and his favorite artist, Richard Wagner (Paul Bildt). Käutner frequently feigns as though he’s about to let the tension boil over into a veritable hot mess, only to exercise some last-second restraint—perhaps mirroring the repressive mechanisms of Ludwig’s fractured psyche. Subtle camera movements and a dynamically stagey mise en scène usher us from Ludwig’s flirtations with Wagner to a chronicle of his relations with women, including the Empress Elisabeth of Bavaria and her younger sister, Duchess Sophie Charlotte, to whom he was at one point engaged. Finally, we’re transported to the innermost chambers of one of his most incomparably over-the-top castles, where he grapples with the schizophrenia of his brother Otto (a fresh-faced Klaus Kinski) and the deterioration of his own mind and health. Käutner’s film takes its own reverence and florid artifice in stride, using it to advance a deceptively sophisticated portrait of Ludwig as a sensitive man saddled with the burden of absolute power who attempts, in vain, to build an alternate world into which he can escape.

Sky Without Stars

Käutner’s range was quickly evidenced by the next film of his that I caught, Sky without Stars (1955). It’s utterly remarkable that it premiered the same year as the Technicolor, nearly-but-not-quite-camp Ludwig II: Sky without Stars is a black-and-white story of love obstructed by the border separating the GDR and the FRG that’s positively neo-realist by comparison. Anna (Eva Kotthaus), an East German factory worker, sneaks over to the West, abducts her own son, meeting and falling in love with a compassionate cop named Carl (Erik Schumann) in the process. So begins a slow-burning romance replete with many daring, unsanctioned visits to their respective sides of the Iron Curtain. A sense of tragic fatalism lingers throughout, recalling Nicholas Ray’s They Live by Night in rendering love as being always imperiled and on the run from the cruel world in which it takes root. But if Ray wrung from similar material an existentialist statement about the doomed fate of man in a cold, uncaring universe, Käutner instead sifts out an affecting argument about the terrible consequences of erecting walls between us.

Back to the royal court, this time in early 18th-century London: A Glass of Water (1960) is a high-mannerist comic musical about the political and romantic intrigues going on under the nose of Queen Anne of England, Scotland, and Ireland (Liselotte Pulver). A carousel of gentry schemers, scoundrels and lovers (including a rare and thoroughly hammy performance by Gustaf Gründgens, of Fritz Lang’s M) is set into motion as the Duchess of Marlborough (Hilde Krahl) tries to get some momentum going for Great Britain’s potential entry into the War of the Spanish Succession with tactics that wouldn’t feel out of place on The Bachelor. Even more so than in Ludwig II, Käutner bares the device with maximum conspicuousness, its scenes unfolding within the confines of some of the least verisimilar sets you’ve ever seen, geometric confections that more closely resemble padded cells than regal halls. A Glass of Water is rather unmistakably a trifle, though perhaps intentionally so: retrospective curator Olaf Möller’s introduction framed the film as a preview of the stylistic techniques with which the director would later experiment even further in his television work, yielding both a colorful glimpse of things to come and a unique whatsit in its own right.

Käutner’s best-known film, Black Gravel (1961), is the sort of movie that immediately leaves one completely baffled as to why it hasn’t been canonized. A take-no-prisoners noir set in the West German village of Sohnen around the site of an American airbase in progress, Black Gravel begins starkly, with Robert (Helmut Wildt), a trucker who illegally sells the titular rocks as a side hustle, watching as a colleague arbitrarily murders a Dalmatian they chance upon and promptly dumps its body. It turns out the dog belongs to an old lover, Inge (Ingmar Zeisberg), who has moved to Sohnen with her new, American husband. Their romance is rekindled following some begrudging cat-and-mouse games, only for them to accidentally off a younger, comparatively innocent couple—and thus, let the cover-up ensue. The paranoia in Black Gravel is unbearably tense, arising equally from our anti-hero’s efforts to get away with both an affair and manslaughter, the emergence of a sordid local industry dedicated to keeping the American occupiers drunk and laid, and the ongoing presence of anti-Semitism even after Germany’s denazification. (The latter point landed Black Gravel in hot water with the Central Council of Jews in Germany, leading to the censorship of a scene in which a character is cursed as a “dirty Jew.” History has seemingly distinguished between representation and endorsement and subsequently vindicated Käutner, though: the new digital restoration of Black Gravel, which premiered at this year’s Berlinale but was not shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato in favor of an older 35mm print, has reinserted the excised scene.) A rugged thriller rich with historical, cultural and political interest, Black Gravel’s reputation has been on the rise for some time now, and its rightful place in the pantheon of postwar cinema seems within reach. Hopefully this will also be true of Helmut Käutner—may his body of work, seemingly too polished yet wildly eclectic to be properly appreciated during his lifetime, finally receive its proper due.

Black Gravel

From the too-little-known to a film whose reputation more than precedes it: several of Douglas Sirk’s most beloved melodramas screened in the festival’s annual showcase of original Technicolor prints, though I only managed to catch my favorite, Written on the Wind (1956). It was presented on a dye-transfer 35mm print, but the beginning of the first reel had horizontal scratches that made it feel as though one had to peek at the film’s wondrous, eminently modern opening credit sequence as if through a photochemical fence. (Which isn’t to say that this act of strained vision didn’t confer an intriguing voyeuristic aspect to a part of the cinematic experience usually taken for granted.) But the scratches dissipated soon enough, and Sirk’s consummately Freudian tale of a New York ad-woman (Lauren Bacall) who becomes entangled with a Texas oil baron’s psychically troubled children (Robert Stack and Dorothy Malone) and their better-adjusted childhood friend (Rock Hudson) unfurled resplendently, its vibrant palette as gorgeous as ever and its central drama still pitched perfectly between high-irony and fable-like sincerity. Stack’s performance was especially captivating this go-round: an impossibly wealthy drunk who has it all yet whose capabilities are always in question for one reason or another, he simmers, stews, and stumbles out of ritzy supper clubs, onto private jets and into town cars, and then, once back in Texas, behind the wheel of his fancy drop-top sedan, gunning it to a favored, déclassé watering hole to score a bottle of the disreputable corn liquor that evokes not so much the balance of his (or daddy’s) checking account as the magnitude of his self-loathing. It’s striking how megastar Bacall recedes to the background for much of the film, clearing the way for Stack and Dorothy Malone’s nympho time-bomb to take center stage, with Hudson off to the side, evoking a sturdy man who is exhausted after a short lifetime of keeping these unhinged enfants terribles from going fatally off the rails. But Bacall surges back to the fore in the film’s many times of crisis, effectively adding to the mix a conflicted woman who loves two men—or perhaps two contradictory aspects of Man—one who is always-already wounded and beset with insecurity and paranoia, and one who is ostensibly stable and sensitive yet who is also a transgressor in his own way. Suffice to say that Written on the Wind only gets crazier and richer with each successive viewing, and reminds us of why we keep looking to the history of the medium.