Cannes Interview: Ryûsuke Hamaguchi

This article appeared in the July 15 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

Drive My Car (Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, 2021). Stills: © 2021 Culture Entertainment, Bitters End, Nekojarashi, Quaras, NIPPON SHUPPAN HANBAI, Bungeishunju, L’ESPACE VISION, C&I, The Asahi Shimbun Company

2021 has seen the appearance of two major, challenging new works from Japanese auteur Ryûsuke Hamaguchi. The romantic Demy-esque coincidences that spin the Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy came first, winning the Silver Bear at this year’s Berlinale. In this suite of Hamaguchi’s “short stories,” he plays daft Fate over a ronde of cool literary types and their enchanting missed connections. Like the 2018 diptych Asako I & II, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is touched by melancholic dreaminess. A woman is unsettled by a romantic rendezvous between her best friend and her ex-lover; an unhappy grad student engages her professor and literary idol in a provocative, unpredictable encounter; two women cross paths in a case of mistaken identity that makes something magical of yearning and regret. Failure and disappointment have rarely felt as lovely as in these short parables.

The second film, Drive My Car, which just premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, qualifies as Hamaguchi’s most moving and finely tuned work to date. It is an unconventional melodrama that defies summary—an open and devastating work that, like Chekhov’s short stories or Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964), preserves the mystery of human experience with both elegance and anguish. More than in any previous Hamaguchi film, the palette of emotions expands dramatically as the filmmaker and his company of actors face, without fear, the voids of quiet lives endured in the shadow of loss.

The three-hour Drive My Car (it earns every single minute of its runtime) is a loose riff on the 2015 Haruki Murakami short story of the same name. Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) is an actor, director, and widower putting together a theatrical adaptation of Uncle Vanya, whose title role he has played dozens of times to great acclaim. But when Kafuku gets into a car accident that slightly damages his eyes, the theater company hires Misaki, a young driver played with brilliant understatement by Toko Miura, to drive him around Hiroshima. Soon, driver and director begin to open up to each other about their buried pasts. Most of the film is confined to these conversations inside the car, and the vivid recollections they entail: of Misaki and her abusive parents; the sudden passing of Kafuku’s screenwriter wife Oto (Reika Kirishima), and their dead daughter; the affairs Oto carried out discreetly. As the narrative unfolds, the lives of the characters play out within a theater of memory, unreliable and open to revision.

I spoke with Hamaguchi two days after the premiere of Drive My Car at the Cannes Film Festival. We talked about adaptation, how COVID-19 affected the making of his last two films, and the essential mysteries of acting.

How were you and your work affected by the pandemic?

Of course, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy and Drive My Car were impacted by COVID, which led to them being almost finished at the same moment, which wasn’t my intention. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy was a very independent movie; I shot it whenever I had a bit of time, here and there. In 2019, I started shooting the first and second stories. Afterwards, in 2020, we started shooting Drive My Car. We were supposed to end the shoot way before Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy was released. We were shooting the prologue of Drive My Car in Tokyo, but then we got the notice for the lockdown, and had to stop. We were supposed to shoot the rest of the film in Busan, South Korea, but this became impossible, so we had to come up with another city: Hiroshima. All told, we were interrupted for eight months for Drive My Car, which was such a long delay that I ended up filming the final story of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy in the meantime.

How do you see the relationship between the two films, given that it wasn’t really your plan to have them released to an audience at the same time? Do you see them as responding to one another?

By shooting these four movies [Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is an anthology of three 40-minute stories], I was able to organize my thinking. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy was a completely independent movie, which meant that I was free to do whatever I felt. So it helped me reflect on my past work and also prepare for my future work. The car scene between Meiko [Kotone Furukawa] and Tsugumi [Hyunri] in the first story of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy was a preparation for the car scene between Takatsuki [Masaki Okada] and Kafuku [Hidetoshi Nishijima] in Drive My Car. Certain sex scenes in Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy were also a preparation for Drive My Car.

Script reading and rehearsal is very important to me. This is something we were able to do for Happy Hour [2015], and which we did a bit of for Asako I & II [2018], but my biggest regret for Asako I & II is that we didn’t have enough time to prepare. With Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, I had the freedom to take my time with a cast that was willing to work with me as much as I needed.

Reading the script again and again—without emotion, just getting it hardwired into your head—enables you to say something naturally, even something that is a total, maybe even unrealistic lie. The words become convincing, fully fleshed, in a very natural way.

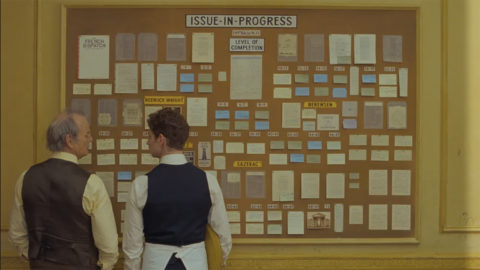

Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, 2021).

Language is a focus in both films: The characters come up against the impossibility of communication, even in one’s mother tongue, as well as the disastrous explicitness of language as a medium. I wonder if this is why you have chosen film as your medium, as opposed to writing literature? Have you ever thought about writing stories or novels?

I won’t deny that I tried once in my life to write novels. But I realized that I wasn’t made for it. I wasn’t good at it. I realized that literature, description, depiction, is not a talent I have. I think I’m quite good at imagining what people might say in a natural way, but describing a full, whole situation is not my strength. What I do is that I write words that will trigger reactions and will be stimuli for the actors.

For me, words and literature are merely media to communicate with actors. It’s never about the text itself. It’s more the concept of what the words will bring to the body of the movie, the storytelling process.

More explicitly than in any of your previous films, Drive My Car takes us into the process of staging a movie: directing, screenwriting, the relationships between actors, and so on. It’s also about the bleeding through between life and art. Did you feel that parts of your lives or the lives of your actors were bleeding through as you made the film?

The central element reflected from my life in this movie would be my thoughts around acting itself. In Drive My Car, you have theater actors. And usually stage acting doesn’t combine well with movie acting. They’re two different things. Because of that, the theme of what acting is, and how one acts well, emerged naturally.

Sometimes, something happens between actors that cannot be shared completely. It’s a secret. Should it be shared with the audience or even with the director? We can argue about that. As a director, I want to share that with the audience, but the only thing I can do is to put the camera in front of the actors. When the acting achieves a really fine-tuned quality, that’s the right moment to place the camera in front of them. And if the result is good, the audience is let in on that secret.

Acting is also central to the Murakami story. On first read it’s not obvious how its cerebral plot might translate to the screen. What made you decide to adapt the text?

I chose it for two reasons: because the characters were in a car, and also because of the questions of acting that the story explored. These two elements immediately attracted me. The main point for me in this whole story is the moment where Takatsuki hits Kafuku in his blind spot. Kafuku is looking down on Takatsuki. He doesn’t have much respect for the young man. But then Kafuku is shaken by Takatsuki’s revelation that you cannot deeply know someone; if you want to really do that, you have to start with yourself. Murakami describes this moment: “Takatsuki’s speech seemed to have emerged from deep within him.” The character is saying something that is true for himself. In my personal experience, I know what Murakami’s talking about. There are many times when people say something, and you can hear in their voice that they are saying something that is true to them.

Now, putting this into an acting situation is where it gets difficult. In the story, Takatsuki, the character, is saying the truth for himself. But in a movie, the actor playing the role, Masaki Okada, must also say what’s true to him. Hopefully through the process I’ve roughly described, the short story and the movie can meet.

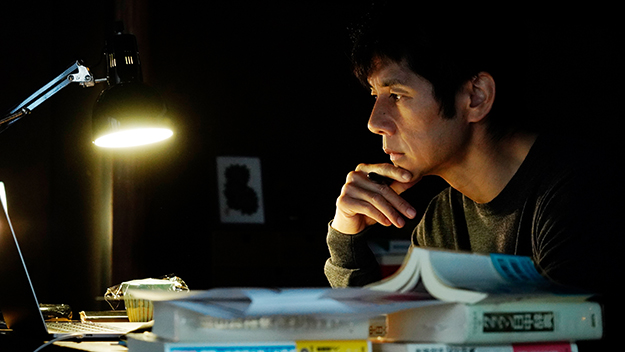

Drive My Car (Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, 2021)

The Murakami story starts with the actor hiring the driver, and out of their conversations, his memories of Oto emerge. In your film, you reverse this order, so that we get the history first, then we live with the ghostly memory of Oto for the rest of the film—a little like Janet Leigh’s character in Psycho. I wonder if you can speak about your approach to adaptation: how do you work on extending some scenes and deleting others?

That is a bit of a difficult question. When I’m structuring a story, it’s not a conscious act. I’m not doing it very intellectually. For this movie, I read “Drive My Car.” I read all the other stories in Murakami’s [short story collection] Men Without Women, in which “Drive My Car” is featured. And I read Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya again and again and again. When I started writing, it just came out as a straight flow. I was able to pick up all of those little details that made such an outstanding impression on me while I was reading. Once this process was done, I compared what I’d written to the original material. And that’s when I realized what I kept and what I changed. But first, I built a framework that I and the actors can respect.

This is where I must acknowledge the work of my co-screenwriter, Takamasa Oe. He was a formidable partner to work with. He was the reader in this process. A bit like Murakami’s wife, who reads his work and says, “This is not really consistent. This is great.” Oe has the same role. Even when the film was becoming less audience-friendly, he would say, “The story is great.” Oe provided a different point-of-view than that of the director or the producer, who both usually function as the audience’s friend—they don’t want to lose the audience. So having Oe as this other voice who respected the story was a great experience.

Thanks to Miyu Mitake Leroy for her intrepid English-Japanese translations.

Carlos Valladares is a writer and critic who has a regular film column in Gagosian Quarterly, and whose work has appeared in n+1, MUBI’s Notebook, and the San Francisco Chronicle. He is currently a PhD student at Yale University in Film and Art History.