By Jan Dawson in the March-April 1974 Issue

Robert Altman Speaking

The filmmaker offers insights on 1973's The Long Goodbye

Most people feel that, with The Long Goodbye, I’ve deserted Raymond Chandler. But Chandler had to be deserted, because Chandler left us in the ’50s. So it’s my interpretation, my presumption, of what Chandler would have remarked about—had he been here to remark.

From the March-April 1974 Issue

Also in this issue

I gave every member of the crew a copy of Raymond Chandler Speaking. I wanted them to read about his fascination with suicide. We transposed that fascination into Roger Wade [the novelist played by Sterling Hayden]. In the book Roger Wade was a faked suicide, he was really murdered. But in my film, he commits suicide. Roger Wade was in a sense Chandler. He was a sort of hero who gave up the struggle. He just didn’t want to deal with it any more. I think he just wanted to escape.

There’s a conversation Roger Wade has with Marlowe on the beach, where he asks Philip Marlowe: “Do you ever think about suicide?” I mean he really told everybody what he was contemplating. He was in a world that no longer accommodated him—and I think suicide fitted that character very well. Our adaptation is really much more about suicide than it is about murder.

I think Marlowe committed suicide, too. One, he committed suicide by chasing after a car through traffic—and he nearly succeeded. In fact, I’m not sure he didn’t. I’m not sure that the other man, the invisible man who was wrapped up in bandages, wasn’t the real Marlowe. He even says to the bandaged man, in reference to a man screaming across the hall: “You tell him it don’t hurt to die.” It’s all preparation for escape.

I think the satire in the film is pointed more at films than it is at Chandler. It’s very hard to satirize Chandler because he was a satirist himself. We also took rather careful note of what he said about Philip Marlowe, that Marlowe was a character who could not possibly exist. So, in order to portray him, we either had to say “this whole thing is fake,” or that this man, who thinks he’s Philip Marlowe, is insane. Or sane.

Elliott Gould in The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973)

We were trying to take the situation of a guy who happens to be a private detective. Now, I really don’t see how anybody could be interested in seeing a private-eye film. I think it’s a very dishonorable profession: it’s never had anything to do with digging up the—more with digging up information that will be applicable for whatever purpose the person who is doing the hiring wants it put to. Well, if the man’s going to be a private eye, then let’s let him be a private eye.

It’s impossible to defend our Marlowe against other people’s ideas of him.When most people say “That’s not Philip Marlowe,” what they really mean is “That’s not Humphrey Bogart.” They’re not talking about Chandler, they’re talking about Howard Hawks. Or about Robert Montgomery, Dick Powell, all those various interpretations of it.

When I came into the project, Leigh Brackett [who helped write The Big Sleep] had already written the screenplay. The producers had obviously hired her because she had written the other. They asked me if I wanted a new writer, and I said no. She came over here, and we talked for three days, simply streamlining the plot, which she did. She knew exactly what I was going to do with the film, I believe. She had no ego about changing the scenes. She was very professional, very good for us. Her first screenplay was pretty much like the finished film. We added a few characters, introduced a situation or two, made a couple of connections—but there were no great changes.

Our Marlowe, like the Bogart Marlowe, always wore a dark suit, a necktie, and a white shirt. His shirts were always done by the laundry; they were starched and they always had creases in the front and down the side. He probably changed his shirt more than he bathed. We figured that his idea of getting dressed up would be to put on a clean shirt with the same suit and the same tie.

The film is satire, and in my opinion it’s dated properly. While we were making the film, we literally called him Rip Van Marlowe, as if he’d just woken up 20 years later and found out that there was absolutely no way to accommodate himself. He really walked through it as a kind of tour guide, realizing he was never a driving force. The only real thing he ever did was to believe his friend—falsely. Everything else he did was an absolute mistake. And he never performed one action in the whole film, except at the end. Everything else was a reaction.

Sterling Hayden, Elliott Gould, and Nina Van Pallandt in The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973)

It’s true that our Marlowe doesn’t have any of the heroics of the earlier movie Marlowes. I don’t have any trust or distrust of heroics. I’m just trying to play devil’s advocate when so many people paint so many pictures of heroes. I think there is an antihero, too—and I think he may in fact be the hero. Most people who are considered heroes are always to be found messing about in someone else’s affairs, and I don’t think that’s very heroic. I guess I have a great deal of affection for fools. I consider myself one. The only people you can have affection for are fools. It’s a matter of trust: if you don’t trust, then affection is not possible. I think being a fool is the only way to be. I don’t think Nixon’s a fool.

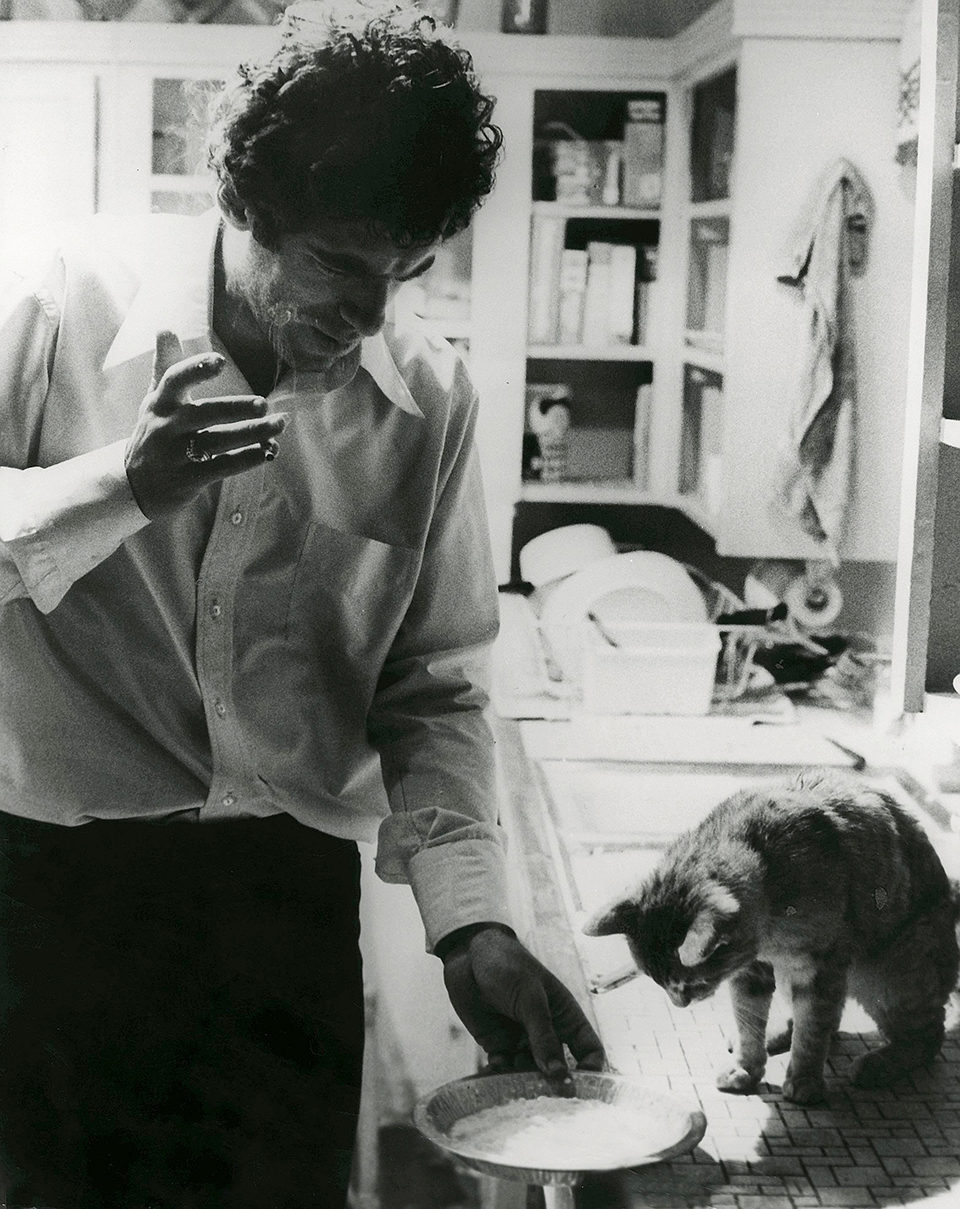

You could say that the real mystery of The Long Goodbye is where Marlowe’s cat had gotten to. I shot the film in sequence; and I think that the most important thing we do in the film is to set up the whole cat sequence at the beginning. That, I think, tells audiences that this isn’t going to be Humphrey Bogart, it isn’t going to be broads and fights. It’s almost obligatory in this sort of film to open up with some very heavy action; we did just the opposite.

Marlowe had no affinity with dogs. He was a cat man. I think you have to be one or the other. You see very few people sitting around their apartments with dogs at their feet and cats on their shoulders—it rarely ever happens. So Marlowe had this cat, this very fickle cat, that wouldn’t stay with him. And every time he came home, he looked for that cat. Although I had the feeling that he knew he was never going to find that cat again. The minute he didn’t give the cat exactly what it wanted, it left him.

In the very opening sequence of my new film, Thieves Like Us, Keith Carradine, who has escaped from prison, is sleeping under a bridge—and a dog comes along. And he befriends the dog, talks to the dog, says, “Do you belong to anybody, or are you just a thief like me?” That night he sleeps with the dog, uses him as a blanket, and they curl up together under the bridge for warmth—and the next day you see him coming into town, and the dog’s with him. A couple of days later, he goes in to see this girl and he says, “You didn’t see my dog, did you?” And she says, “Oh, he ran off with some redneck in a pick-up truck.” And the door slams in his face, leaving him on the other side, and she’s gone, and he says, “Well, that’s okay. Wasn’t my dog anyway.”

This guy and Marlowe know that they can’t expect love, and they live with it that way. In a way, both these men are heroes—well, they’re admirable. I don’t think the word “hero” is applicable.

Elliott Gould in The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973)

It’s been said that Chandler set out to glamorize a World War II code of honor that was left over in the ’50s, and now The Long Goodbye has deglamorized that code because it doesn’t fit into the ’70s. And it’s true: the times have changed the old code. It’s like war. It used to be that everybody was proud of the soldier—the guy who came back with his scar, and would still wear his uniform and have his sleeve pinned up. Now you see a man like that, and you think, “Jesus, that dumb son of a bitch, why did he do that?” Everything changes.

We cut the characters off from anything prior to 1973—other than their behavior. Their behavior indicates that they are not 1973 people: they are perpetuating cultures that come from other times. Roger Wade was like Irwin Shaw, James Jones, Ernest Hemingway—the heavy drinking, the very masculine attitude that there’s really no place for anymore. These people were all frustrated, because they wondered what happened to themselves. Like Eileen Wade [Nina Van Pallandt]: you never see her in a miniskirt, or a low-cut blouse, or with her shirt off like the girls who had the apartment across from Marlowe. Marlowe himself didn’t understand nudity any more than he understood yoga—or yogurt.

Terry Lennox [Jim Bouton] is the kind of character who would win every game he’d play. He’s always the guy on top, the one who’s getting favors done for him—one of those guys of whom you’d say, “Gee, he’s charming,” and yet you know he’d cut your throat if it was to his advantage. He’d never go out and do it sadistically or maliciously. He’s just one of the selfish people. The one thing we left Rip Van Marlowe with was his faith in the thesis that a friend’s a friend. But his friend was Terry Lennox. And when you depend totally on one truth, and that truth denies you, then you’re back to suicide again. We demand such rigid things from drama, and in our own lives we accept anything .

So I think Marlowe’s dead. I think that was “the long goodbye.” I think it’s a goodbye to that genre—a genre that I don’t think is going to be acceptable any more. There’s also a lot of personal long goodbyes in it: making a film in Hollywood, and about Hollywood, and about that kind of film. I doubt if I’ll do that again.

Jan Dawson, who interviewed Robert Altman last October [1973], works for the British Broadcasting Corporation.