Easy Rider

In 1970, following the phenomenal worldwide, cross-cultural success of Easy Rider, Dennis Hopper appeared on the Johnny Cash show. You can see an excerpt on YouTube, during which Hopper—wearing denim, a Stetson, and centrally parted long hair—removes his hat and recites the entirety of Rudyard Kipling’s “If.”

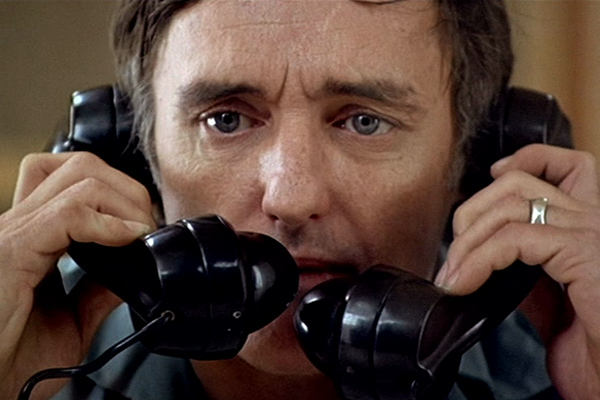

The poem is delivered in a single spotlit shot, with the camera slowly moving in. Hopper’s enunciation is unexpectedly crisp, earnest, and assured. Not only does he know the words, he seems to have internalized them. “If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster / And treat those two imposters just the same…”

Somehow Kipling’s anthemic invocation of English stoicism and self-knowledge translates stirringly into a vehicle for Hopper, age 33. “If you can make one heap of all your winnings / and risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss / And lose, and start again at your bginnings…” As the camera locks into a close-up, Hopper is holding two admonitory fingers in front of his blazing eyes—a cowboy Jesus as imagined by Pier Paolo Pasolini. The end of the poem triggers a musical cue and massive applause, and Cash, towering over Hopper, steps in to shake his hand. “I’m gonna tell that to June Carter,” he declares.

The Last Movie

The episode is silly and wondrous and, for anyone who cares about Dennis Hopper, resoundingly poignant. You realize he had 40 more years of triumph and disaster ahead—many occasions to remind himself that he’d beaten the odds, accomplished fine and great things, and outlived his most calamitous losses, his mistakes and missteps.

You might also realize that virtually no one but Hopper could have provided, on network television, a plausible bridge between Rudyard Kipling and Johnny Cash.

Just so, from early on and over the years, as a performer, filmmaker, aesthete, certified “rebel,” hipster, and survivor, Hopper was an anomaly, straddling multiple eras and attitudes, linking unlikely people, mediums, worlds.

He acted in my first film, a short, in the fall of 1985. He was, in fact, the first professional actor I ever worked with—his scenes were the first up, the real beginning for me. I’ll always be sentimental about him.

It was during his crowded post-rehab year, when he acted in six features back to back, accepting roles—in Blue Velvet and River’s Edge, most notably—that had been first rejected by Harry Dean Stanton. Stanton had determined that he was no longer available to portray psychopaths, killers, and drunks; Hopper, by contrast, was ready for anything—including my rather opaque project, a loose, contemporary adaptation of a chapter from Mikhail Lermontov’s 19th-century novel, A Hero of our Time, to be shot in 35mm, in black and white.

The American Friend

I remember my first glimpse of him, staring down at me from the window of his Gehry-renovated, postmodern palace in Venice Beach, when I was first invited to visit. He looked furtive and spooked, like Tom Ripley in Wenders’s The American Friend; then he reappeared at the door, transformed into the person who became familiar in months ahead—unfailingly mild-mannered, deferential, modest, lucid. We had Kansas in common—though I grew up in the Northeastern corner, near Kansas City, where Dennis, born in Dodge, landed in his high-school years. We shared, I’d venture to say, a mid-Westerner’s underlying, uneasy earnestness, despite whatever protective coloring had been acquired down the road. He explained, at any rate, that things had been rough but he was looking after himself. He confided, with an air of wonderment, that he was doing his own laundry. He had that quick smile, that crackling laugh.

I cast Hopper (predictably, alas) as the pathologically violent villain. For the Los Angeles update, his character—a Tartar bandit in the original—became an unhinged record producer. Coordinates from the source material hovered over the action like a dissolving vapor trail. The point was to show contemporary men measuring themselves against heroic lost codes. (I was, need I admit, 25 years old.)

Hopper’s patience and cool-headedness extended through the shoot, which covered two days and one night during a break in the filming of Blue Velvet. I steered him toward restraint, some notion of low-key naturalism. That is, in my movie he looks like Blue Velvet’s Frank Booth, but drained of color and decidedly subdued. “It’s funny,” he said at one point, “David kept saying ‘More, more!’ And you keep asking for less.“

Blue Velvet

He brought a quality of romantic fatalism to the part, and a slow-burning humor. “I don’t think you’re taking your life seriously,” was a key line, delivered matter-of-factly to the woman who abandoned him for the story’s putative hero. Hopper finished his compact monologue, his biggest scene, with an understated sense of anguish. His concluding words: “I used to be somebody more interesting than I am now.”

He tapped into the script, believed in it. I can say this with some certainty because he recommended me to Wim Wenders, who was searching for a screenwriter for his globe-spanning road movie, Until the End of the World. I got the job—another story, but the point is I have double cause to be eternally grateful to Hopper.

I struggled, fitfully, to finish the short over the next three years. Eventual acceptance by Sundance seemed anti-climactic; I was more pleased to have the movie included in a traveling Hopper retrospective, From Method to Madness, organized by the Walker Arts Center in 1988. (J. Hoberman’s catalog commentary furnished a definitive rumination on Hopper’s achievement in movies. Somebody should reprint it, pronto.) By then, I’d moved on to my first feature, Twister, adapted from a novel by Mary Robison. I adjusted the part of the Kansan patriarch—a soda-pop magnate who doesn’t kill or threaten anyone—with Dennis in mind. He agreed to do it, but by the time financing arrived he was booked on another film and the role went to… Harry Dean Stanton.

Out of the Blue

I believed in Hopper as a filmmaker—both as a craftsman and a visionary. Easy Rider looms, of course, as a cultural watershed, a phenomenon as much as a motion picture. The idea that Hopper actually directed it seemed slippery to just about everyone but him. But The Last Movie, by contrast, was unmistakably his, and he was vilified for it. I saw it in 1986 at the Nuart Theater, followed by a Q&A session with Hopper. Yes, the film is a self-conscious gallop and lurch down a hall of mirrors, but I remember being impressed both by how accessible it is, and how emotional. (The long tracking shot following Hopper’s character outside a party, culminating in tears, still registers as one of the most powerful things he’s done.)

And then there’s Out of the Blue (80), all the more miraculous for being a last-minute plunge, as Hopper was enlisted to take over the film after two weeks of shooting under another director. He refashioned the story, its focus and temper, coming up with an expressionistic social critique worthy of Fassbinder or Nicholas Ray, a movie that crashes a sense of working-class reality into punk nihilism and an appreciation of the absurd. He sank his own money into it, and waited three years for the distributor to release and then withdraw it when the film was met with critical incomprehension and dismal sales. It’s plainly a film ripe for rediscovery, but one measure of its greatness is that it’s probably as assaultive now, as painful and hard to take, as it ever was.

I visited the set of Colors in 1987, and remember an energized Hopper, palpably grateful to Sean Penn, without whom he couldn’t have made the movie. Colors was conventional and compelling enough to warrant the hope that Hopper was in it for the long haul, a committed, employable Hollywood filmmaker. The picture provided evidence that he could find his way into a briar patch of hectic, heightened drama and, with the mutual encouragement of strong actors, make himself at home. But his next three directorial jobs—The Hot Spot (90), Backtrack (90), Chasers (94)—showed few traces of conviction or daring. As a filmmaker, he was no longer playing for high stakes. It was as if he’d been persuaded that an aggressive personal style was something to run from or hide.

Hoosiers

I’m guessing now, but the realignment of his political views—the writer/director of Easy Rider and Out of the Blue became a Republican in the Eighties, and was eventually vocal about it—seemed to originate from a similar move toward self-erasure. Or it’s just simple proof that he was tired of being on the losing team, tired of failure. The Last Movie (71), as aptly summarized by J. Hoberman, had been “an ode to failure.” Out of the Blue must have felt like a dead end rather than a pinnacle. And then it’s a safe bet that Triumph and Disaster stop looking like impostors once you’ve been nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor (for Hoosiers, 86) and seen your salary elevated by an appearance in a genuine blockbuster (Speed, 94).

We reconnected, briefly, in 1994 when Dennis came to New York to act in Search and Destroy, directed by David Salle (another Kansan) from a script I’d adapted from Howard Korder’s play. (Hopper’s role, as Dr. Luther Waxling, involved a send-up of televangelist Gene Scott, whom Hopper, in icier moments, rather resembled.) I was directing my own movie, Nadja, across town. As if to confirm the proliferation of connections still linking me to Hopper’s world, I told him that Nadja was produced by David Lynch, and Peter Fonda had a prominent role in it. He seemed amused, but groused that Fonda owed him a few million dollars. When Fonda and I accompanied Nadja to Cannes the next year, and Hopper was also working the room, somebody noted the publicity-friendly fact that Fonda and Hopper hadn’t cruised the Croisette together since the glory days of Easy Rider. I sat beachside tent while a succession of interviewers flowed through with questions. It was, from what I could tell, one of Hopper’s finest performances. He was relaxed, attentive, gracious, funny. He acted as if all was forgiven between Peter and himself, and he faced each familiar dim question as if it sparkled, reflecting his own hard-won optimism.

I find myself bristling when I read the caustic, condescending account of Hopper’s career in David Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of Film. Thomson has high praise for Frank Booth, but little love for much else in the Hopper canon. He recognizes that the actor became a simulacrum of his former self. (Yes, but really, past a certain point, who isn’t?) Hopper’s more recent role—as guardian angel and godfather, ambassador from a more reckless era, a renegade emeritus, primed to bless and encourage younger intransigent types—is hardly available for critical review, but from the Eighties onward Hopper took on this role with great generosity of spirit. I feel it necessary to insist on this, of course, speaking as one of its beneficiaries.

It was still early, during our first day of shooting, when he took me aside for a kind of Polonius moment.

“The most important thing in movies,” he confided, “is timing.”

A pause, then: “Timing and lighting, actually.”

Another pause, then he corrected himself: “The most important things in life are timing and lighting.”

Without examining it too closely, I still believe this statement to be unmistakably true.