The Devil Finds Work: James Baldwin on Film

Go Tell It on the Mountain

“The rise and fall of one’s reputation . . . What can you do about it?” James Baldwin, then 61, said to The New York Times just before the release of Stan Lathan’s film adaptation of his debut novel Go Tell It on the Mountain. “Any real artist will never be judged in the time of his time; whatever judgment is delivered in the time of his time cannot be trusted.”

At the time of that interview, in 1985, the Harlem-born Baldwin was living in France and still writing, but no longer the blazing star in the cultural firmament that he’d once been. In 1948—before mass movements for African-American or gay civil rights had kicked into gear—the 24-year-old Baldwin abandoned the United States for the more tolerant (for black Americans, at least) climes of Paris. Here he completed the vivid, semi-autobiographical Go Tell It on the Mountain—about a day in the life of the teenage son of a fiery Pentecostal preacher—and promptly became a sui generis literary sensation.

Go Tell It on the Mountain

Baldwin went on to fearlessly broach complex and controversial subjects—entrenched American racism, cultural imperialism, homosexuality (including his own, never disguised)—in a string of novels and essays, all of which are distinguished by an instantly recognizable prose style of elaborately punctuated yet fluid sentences, and a tonal blend of grave realism, pulpit-style passion, and arch humor. Baldwin also cut a swath as an orator, returning intermittently to America, particularly at the height of the civil-rights movement, to comment on the myriad societal ills of the nation he’d left behind. Famously, he was barred from speaking at the March on Washington in August 1963 after clashing with Robert Kennedy, who believed that his words would be too militant. Malcolm X, who referred to the event as “the farce on Washington,” observed that Baldwin was censored because he was “liable to say anything.”

Today, some 30 years after that Times interview, and nearly 28 after his death (from esophageal cancer, in December 1987), Baldwin’s reputation has never been stronger, or his work so frequently cited. In a time of protests in Ferguson and Baltimore, #BlackLivesMatter, and the compression of names like Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, and Samuel DuBose into grim hashtags of their own, Baldwin’s darkly diagnostic words strike a chord that’s simultaneously cacophonous and clear as a bell. This summer’s publication of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me—a nonfiction treatise on the interconnected, intractable social problems of white supremacy, corrosive hyper-capitalism and anti-black racism in America, which is structured, like Baldwin’s own The Fire Next Time (63), as a letter to a younger relative—has prompted a further renewed interest in his work.

* * *

At a moment when Baldwin’s influence is deeply felt, a wide-ranging series this month at Film Society of Lincoln Center, “The Devil Finds Work” spotlights a less vaunted but no less essential aspect of Baldwin’s artistic life—his vigorous engagement with cinema: as a fan; as a rigorous and perceptive critic; as a would-be screenwriter; and as the subject of numerous documentaries, both television and film, which showcase his fiery oratorical skill and capacity for perspicacious reflection.

With his fascinating, preternaturally craggy face, mellifluously louche voice and sumptuously rolling—yet precisely controlled—cadence, Baldwin was equally compelling on camera as on the page. Many nonfiction filmmakers recognized this fact, and captured him in action in numerous contexts and territories.

The Negro and the American Promise

Shortly after Baldwin’s confrontation with Robert Kennedy over his non-participation in the March on Washington, he was interviewed by sociologist Kenneth Clark for the Boston public television special The Negro and the American Promise (63)—Malcolm X and Martin Luther King were also interviewed separately. Baldwin’s riveting segment finds the author in despairing mood: with huge, near-sulfurous eyes ablaze, he speaks of being “terrified at the moral apathy—the death of the heart which is happening in my country.”

In spring of the same year, San Franciscan media activist Richard O. Moore accompanied and filmed Baldwin (alongside Youth for Service Executive Director Orville Luster) on a tour through the black-majority Bayview/Hunter’s Point and Fillmore districts of San Francisco—the result was Take This Hammer, filmed and released by KQED. The pair sought to portray the real experience of African Americans in what was considered America’s most liberal city. Baldwin’s unsparing observations paint a grim picture, as he compares de jure segregation in the south with its de facto equivalent in the rest of the Union.

Take This Hammer

The film’s third act, in which Baldwin and Luster interview a group of young black men, is its strongest sequence. The men are searingly honest about their employment woes, urban renewal (which Baldwin elsewhere termed “Negro Removal”), and arbitrary police brutality. Neither Baldwin nor his young interviewees temper their grim observations, and it is refreshing in today’s climate of overly polished media sound-bites to hear such untrammeled honesty. Toward the film’s end, Baldwin offers a stark depiction of the perils of everyday life for African Americans: “I’ve got nieces and nephews; I can’t protect them. They’re in tremendous danger, every hour that they live, just because they’re black.” In the light of appalling recent cases like the Charleston church shooting, the police killings of 12-year-old Tamir Rice (who was holding a toy gun), and Eric Garner (who was selling loose cigarettes), this sentiment resounds as painfully true today.

A number of films in the FSLC program reflect Baldwin’s peripatetic movements across the globe. These include James Baldwin in Paris (71), a piquant portrait of the author in a variety of symbolic locations; and James Baldwin from Another Place (73), an absorbing short, the intimate nature of which is signaled by the opening shot of Baldwin waking up, in his tighty-whiteys, in his bed in Istanbul (Baldwin first shored up in Turkey in 1961, and returned periodically in the coming decades). The remainder of this meditative, vérité-style portrait features Baldwin—in both voiceover and interview—musing philosophically on his expatriate status, the peculiar American fascination with sexuality, and the generosity of the Turkish, all while ambling around a variety of eye-catching Istanbul locations.

Baldwin’s Nigger

Even more fascinating is Baldwin’s Nigger (68), the debut film by the Trinidad-born, British-based director Horace Ové. Over 45 too-short minutes, Baldwin and the black American comedian Dick Gregory address a predominantly Afro-Caribbean audience in London on the subject of the social situation for black people in Britain and the United States. There’s an unforced honesty to the whole exchange, arguably engendered by the near total absence of white faces—which is not to say it doesn’t become prickly at points: the audience members give their American guests as good as they get. In the course of the dialogue, Baldwin boldly questions received, binary notions on race: “White men lynched Negroes knowing them to be their sons. White women watched men being lynched knowing them to be their lovers . . . How are white Americans so sure they are white?” Here he alludes to the dark secret of racial mixing so scrupulously buried in many “white” American families and those in the “New World.”

As Baldwin aged, his on-camera contributions became more reflective and elegiac. He gives a warmly humorous and vividly descriptive interview in a portion of William Miles’ I Remember Harlem (81), an epic telling of the community’s 350-year history as the cultural hub of African-American life. Dick Fontaine and Pat Hartley’s I Heard It Through the Grapevine (82), meanwhile, is a personal essay film-cum-travelogue written by Baldwin, who returns to key sites of the civil rights struggle 20 years later to speak candidly with participants and fellow commentators, and to observe what has changed and what has remained the same. The somber film rejects a soothing narrative of social progress to expose how deep-rooted structural inequalities along racial lines manifest in myriad ways over time.

I Remember Harlem

In 1989, two years after Baldwin’s passing, Karen Thorson released the gorgeous, profoundly moving documentary tribute, James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket (its title is a reference to a collection of Baldwin’s writings from 1985). Thorson deploys evocative archival footage to conjure the atmosphere of Baldwin’s formative years, from 1930s Harlem, to the cauldron of his father’s fundamentalist church, and the languidly cool émigré haven of Paris in the postwar years. She also integrates scenes from his funeral service, a panoply of newsreel clips (many of which are dotted throughout the FSLC program), and collects insightful testimony from an array of black literary legends (Maya Angelou, Amiri Baraka, Ishmael Reed). With its gentle, muted tone and raft of information, The Price of the Ticket coheres to constitute a fitting tribute to a public figure of unparalleled range and influence.

* * *

“The Devil Finds Work” series borrows its title from Baldwin’s brilliant book-length 1976 essay, which blends a candid autobiographical articulation of his cinephilia with a frank critique of the fraught intersection between Hollywood’s industrial practices and its limiting representational approaches. (The book is only 127 pages long, and once picked up, is extremely difficult to put down.)

At its opening Baldwin recounts how, as a deeply religious child in Harlem, he fell under the spell of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, reading it repeatedly, and seeing his own family’s struggles reflected in the quest for freedom that defined the French Revolution. When he saw Jack Conway’s 1935 film adaptation, he gained an early understanding of the medium’s ability to shape malleable minds and conjure powerful alternate realities: “I had lived with this text all my life, which made encountering it on the big screen of the Lincoln Theater absolutely astounding,” he writes. “I felt very close to the actors. My first director was instructing me in the discipline and power of make believe.”

A Tale of Two Cities

Baldwin subsequently interrogates the pernicious aspect of cinema’s myth-making capacities in a succession of sharp takes on Hollywood favorites. He’s scornful of the liberal pieties which infest and circumscribe ostensibly progressive fare like In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. He is extraordinarily insightful on the knotty homosocial, interracial entanglements of proto-buddy movie The Defiant Ones, in which Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis play escaped convicts from a chain gang in the South who are literally chained together (“It is impossible to accept the premise of the story, a premise based on the profound American misunderstanding of the nature of the hatred between black and white”). There is also room for a startling digression into the sexual politics of David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia; a catty thrashing of Billie Holliday biopic Lady Sings the Blues which, in his words, has “a script as empty as a banana peel, and as treacherous”; and, in closing, a disturbing extrapolation from William Friedkin’s notorious The Exorcist (“The mindless and hysterical banality of the evil presented . . . is the most terrifying thing about the film. The Americans should certainly know more about evil than that; if they pretend otherwise, they are lying, and not only blacks—many, many others, including white children—can call them on this lie”).

Baldwin also discusses in wry yet painful detail his experience of flying to Hollywood in 1968— over the vehement protests of his friends and family—to adapt Alex Haley’s autobiography of Malcolm X for the screen. Baldwin found himself at the mercy of a Hollywood machine which pressured him to make drastic changes, including the removal of any suggestion that Malcolm’s trip to Mecca could have had any political implications or repercussions. Baldwin left the project, and remarked: “I think that I would rather be horsewhipped, or incarcerated in the forthright bedlam of Bellevue than repeat the adventure.” Although traces of Baldwin’s script remained when Spike Lee finally got the film made in 1992, his surviving family asked that his name be removed.

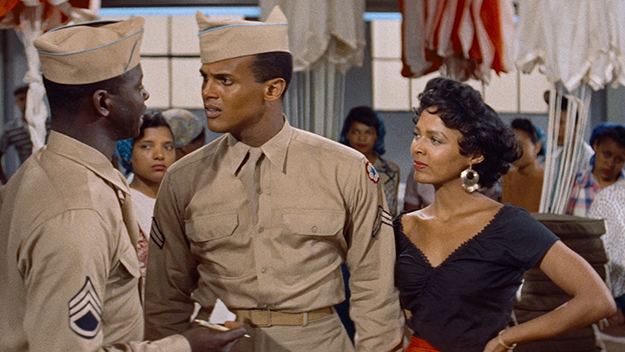

Carmen Jones

It’s worth noting that the The Devil Finds Work was not Baldwin’s first foray into film criticism. In the 1955 collection Notes on a Native Son, he wrote beautifully on Otto Preminger’s all-black musical Carmen Jones, combining his trademark aptitude for a witty turn of phrase (“Mr. Belafonte is not really allowed to do anything more than walk around looking like a spaniel”) with deeper insight (“The most important thing about this movie . . . is that the questions it leaves in the mind relate less to Negroes than to the interior life of Americans”).

Unsurprisingly for a committed, globetrotting aesthete, Baldwin would also look outside the American cinema for enrichment. In a 1960 essay entitled “The Northern Protestant,” he praised Ingmar Bergman’s warped psychosexual melodrama The Naked Night aka Sawdust and Tinsel—about the romantic travails of an etiolated circus ringmaster (Åke Grönberg)—as “one of the most brutally erotic movies ever made.” Meanwhile, Baldwin’s celebrity status and frequent American presence in the 1960s brought him into close proximity with a number of the era’s major stars, including trailblazers like Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier. His closeness with the latter resulted in a poignant, insightful feature on the actor in a 1968 edition of Look magazine.

Baldwin’s take on the compromised lot of the black performer in Hollywood—as refracted through the prism of Poitier—is worth repurposing in full:

The industry is compelled, given the way it is built, to present to the American people a self-perpetuating fantasy of American life. . . And the black face, truthfully reflected, is not only no part of this dream, it is antithetical to it. And this puts the black performer in a rather grim bind. He knows, on the one hand, that if the reality of a black man’s life were on that screen, it would destroy the fantasy totally. And on the other hand, he really has no right not to appear, not only because he must work, but for all those people who need to see him. By the use of his own person, he must smuggle in a reality that he knows is not in the script.

Here Baldwin’s words presage satirical films like Robert Townsend’s Hollywood Shuffle and Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, both of which lament the lack of complex roles for black performers in mainstream entertainment, and chart the existential crises of representation which strike such stymied individuals. Moreover, for as long as black actors continue to be rewarded by the establishment for playing maids, slaves, criminals and welfare queens, Baldwin’s trenchant words will continue to bear an authentic and acrid tang.