TCM Diary: Kaufman & Hart, Writers at Work

The Man Who Came to Dinner

If great writing, to borrow Edison’s view of genius, is one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration, the movies have always had a hard time showing the 99 percent. A scribe at a keyboard is not the most vibrant cinematic subject, and the creative process which consists of staving off self-doubt and distraction is too interior to translate lucidly to the screen. Thus we get origin stories for authors, and their actual labor overshadowed by a montage of events. Moss Hart was supposedly inspired to write The Man Who Came to Dinner (with George S. Kaufman) when acerbic critic Alexander Woollcott paid a visit to his country house: Woollcott demanded a milkshake and cookies before bed, ordered the heat be turned off, usurped his host’s bedroom, and slandered the servants. In William Keighley’s 1942 film version of the Kaufman and Hart play, we see a seamlessly witty, flawlessly timed loose reenactment of these events —but omitted are the months of tedious, agonizing labor necessary to produce an “effortless” work.

If anything is more laborious than writing, then, it’s dramatizing the working writer. No doubt this is why even the best author biopics tend to focus on research (Capote), the spoils of fame (Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle) or self-spoliation (Barfly), overcoming mental or physical handicaps (An Angel at My Table, My Left Foot), or, at best, the discussion of craft with colleagues and acolytes (last year’s The End of the Tour). The film that perhaps burrows deepest into the writer’s consciousness while avoiding conventional arcs or bromides is Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, which integrates three stories by Yukio Mishima into a singular study of the fanaticism that fueled his art and curtailed his life.

Although less revelatory, and guilty of the elisions and whitewashing that blight most wordsmith bios, Dore Schary’s Act One, a 1963 adaptation of Moss Hart’s memoir, focuses on a phase of development we’re not often shown: the rewrite. The simple fact is that literary works do not spring forth from Zeus’s head, fully grown and arrayed in armor. They’re subject to peer review, editorial revision, and public rebuff, and this is true regardless of the length and medium of the piece. (Rest assured you’re not reading a first draft of this article.) It is thus that fledgling dramatist Moss Hart (played in Act One by fledgling actor George Hamilton) spends the better part of 1930 reworking his first attempt at comedy, Once in a Lifetime, with the help of eminent playwright George S. Kaufman (Jason Robards).

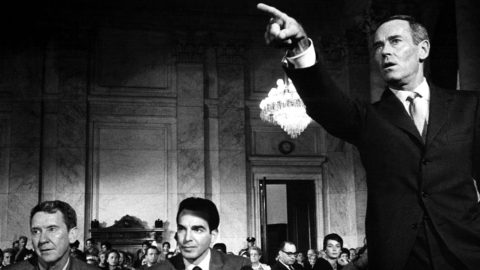

Act One

Having scratched out a manuscript on the Coney Island shore, and—in what may not amount to the most credible depiction of the writing process—on the subway train, Hart is told by one producer that the work “lacks definition,” and asked by another to team up with Kaufman. The hard-bitten veteran opens to the third scene of act one, “trimming the underbrush” with his red pen. When the green-as-grass Hart thinks the play has been saved by a few minor cuts, the cantankerous Kaufman realizes how daunting a task he’s undertaken. From there we watch as the two men in their smoke-filled chambers of creativity (Kaufman’s hotel room and Hart’s favorite delicatessen) hammer out a version they deem Broadway-worthy—but a tryout audience in Atlantic City has other ideas. This necessitates more rewrites; more tensions within and without; more loitering in lobbies, cringing as crowds receive their words in stony silence; more arguing over whether the problem lies in the second act or the third.

Of course the outcome is never in question, and in reality must have been harder-won than the epiphanic way in which it’s presented here. Hamilton later complained that writer-producer-director Schary removed all the ethnicity and genius from the source material—though it’s unlikely that he would have been cast had either been sought. Hair slicked back like an ’80s Hollywood villain and lacking his signature bronze burnish, Hamilton is painfully wooden in the lead. Luckily, as the scarf-clad, eyebrow-arching Kaufman, Robards runs away with the show. While it could have benefitted from still more elaboration on their working methods, Act One ably depicts a seldom-acknowledged stage of composition, and renders one of Broadway’s most fascinating duos at the dawn of their improbable partnership.

The jewel of that association, which includes the Pulitzer- and Oscar-winning You Can’t Take It with You, might well be The Man Who Came to Dinner. True to Kaufman and Hart’s form, it’s a sophisticated, living-room-bound comedy of manners and eccentricity, playing off what film scholar Jeanine Basinger characterizes as the universal fear that an undesirable party will come for a visit and never leave. Here it is Woollcott surrogate Sheridan Whiteside (Monty Woolley), a famed New York humorist invited to dine at the home of a prominent Ohio businessman. When he slips on the icy steps and injures his hip, Whiteside is forced to remain in Small Town USA until fully recovered—in the interim annexing the household, terrorizing the maids and physicians on site to aid him, inviting his outrageous theatrical friends to keep him company, and receiving a menagerie of live “presents” that includes a family of penguins and an octopus.

The Man Who Came to Dinner

The Man Who Came to Dinner is a writer’s piece in every sense of the word. Whiteside is himself a renowned wit, drafting copy for a radio broadcast dense with quips. The minor characters that fly in to trade badinage with him are all based on Kaufman and Hart’s fellow wags and scribes from the Algonquin Round Table, including Dorothy Parker, Noël Coward, and Harpo Marx (reimagined here as “Banjo,” and incarnated so indelibly by Jimmy Durante that revivals of the play tend to model the character more on him than Marx). Some of the references show their age, but as dispatched by the bearded, bellicose Woolley in a role he was born to play, Kaufman and Hart’s withering verbal arrows (“You have the touch of a love-starved cobra!”) always find their mark. “Did ya ever get the feelin’ that ya wanted to go, but still have the feelin’ that ya wanted to stay?” Banjo is wont to ask. Anxious indecision may be the writers’ curse, but for the privileged few like Kaufman and Hart, it can also serve as their muse.

Act One airs November 22, and The Man Who Came to Dinner November 24 on Turner Classic Movies.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.