Make It Real: The Cinema of Transition

The Iron Ministry

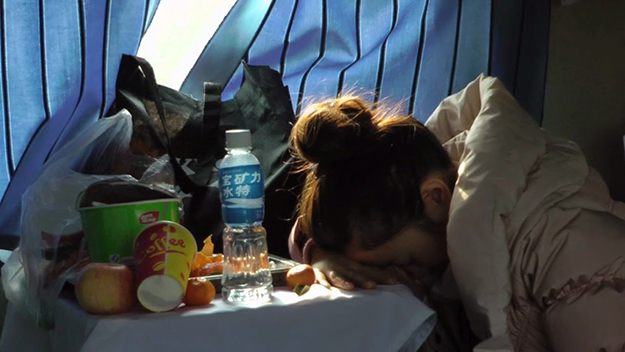

An attendant pushes a cart down the narrow aisle of the train. He sells some packaged snacks and soft drinks as he goes, but mostly he disappoints those hungry for instant noodles, which are sold out. Passengers swing their legs out of the way, or stand aside in the aisle for as long as it takes the cart, and the camera, to barely squeeze past, before returning to filling every available space on the train like rain puddles reforming behind the tires of a car. We’re aware of the camera’s presence in the scene, and it’s also acknowledged by most of the people it passes—it’s both conspicuous in this ordinary context and just another thing to accommodate as people pile on and off, as the landscape dashes past the window. Movement isn’t just the conceit of The Iron Ministry, which was filmed from 2011 to 2013 entirely on trains throughout the People’s Republic of China—it’s the subject, the milieu, the point.

Over the course of the film’s 82 minutes, people are seen commuting to jobs far away from their hometowns. People (and businesses and developers) are riding into areas traditionally unreachable by rail. People are taking old-world customs onto newfangled trains. People are experimenting with, and discovering the limits of, class mobility. People are adapting to change, and contemplating where to move next if things don’t change. The in-transit The Iron Ministry (which is screening for a week at the Museum of Modern Art) works quite well as a metaphor for a society in transition, but thanks to director J.P. Sniadecki’s flexible and attentive approach, the metaphorical is led by the moment. No need to board the train looking for ways to illustrate China’s societal movements when it’s practically everywhere you look, and seemingly on everyone’s minds. The fact that Sniadecki is an American filmmaker actually helps to realize this communal portrait of another country. Not only are he and his camera notable to those he encounters, his being an outsider seems to provoke a self-consciousness—the subjects tend to know that they and their ways of life are suddenly being observed from an outside perspective. (It also doesn’t hurt that Sniadecki speaks Chinese, and is game to accept cigarettes, shots of vodka, and bites of marinated chicken along the way.)

The Iron Ministry

When The Iron Ministry played at film festivals last fall, it was often viewed within the context of Sniadecki’s association with the Sensory Ethnography Lab—the Harvard-based group of loosely affiliated filmmakers still leading the charge for formal innovation and an experiential cinematic ethos in documentary filmmaking. From that vantage, it was tempting to focus on the film’s formal aspects, and furthermore to see its particular approach as being less rigorous than that of SEL-associated films like Leviathan and Manakamana. Abstract imagery like that of an early shot of spent cigarettes buoyed by fetid, possibly urinal water, are merely an element of The Iron Ministry, whereas shots of that sort comprise nearly the entirety of the extraordinary Leviathan. And instead of single-take journeys up and down the same cable car route in Manakamana, Sniadecki’s film takes place on various trains over several years—a marked contrast with his earlier SEL effort, The People’s Park, which is comprised of a single 78-minute shot on a summer afternoon. Yet I prefer Sniadecki’s latest to that previous effort precisely because it’s less concerned with serving a nifty formal conceit, and instead endeavors to see more clearly what’s happening, and hear more intently what’s being said. The camera never stops moving in The People’s Park, never gets waylaid from its mission even when compelling things pass before us, while in The Iron Ministry it repeatedly stops to engage with passengers or listen in on conversations, and without sacrificing a larger sense of movement.

Thankfully, for its run at MoMA this week, The Iron Ministry can be seen in a different, less conscripted context. It’s playing concurrent with the Cinema on the Edge series of recent Chinese independent films, which is ongoing at various theaters around New York City through mid-September. Organized by Sniadecki along with producer and distributor Karin Chien and critic and curator Shelly Kraicer, the series is a selection of films programmed for the embattled Beijing Independent Film Festival, which has either been disrupted or canceled outright due to government censorship since 2012. Surveying the documentaries chosen for the series, I was struck by the formal mutability on display, and moved by the degree to which that mutability arises in response to the cultural and societal instability these filmmakers are living through. Their formalism isn’t fueled by theory, but by the world—and their country, and their rapidly changing towns, and their destabilized families—as they see it.

Stratum 1: The Visitors

In Stratum 1: The Visitors (13), oral history meets science fiction meets black comedy meets experimentalism, among other things, as two young men seek to reclaim living and workspaces that have been dismantled by widespread and rapid development. They stand upon mounds of bricks, and within hollowed-out, floodlit rooms, telling highly personal stories about growing up in Tongzhou, a Beijing suburb. Their anecdotes are often only obliquely related to these environments, which actually serves to widen the scope of loss, powerfully asserting that these trash-heaps are a violated homeland. Then, as up-tempo electronic music blares, and the camera shoots them heroically from behind, our ambassadors walk and walk, from the leveled old village to the brand-new modern town and onward to the outskirts, where dump trucks deposit bricks from dismantled houses. Dirt gets piled on top of the rubble, but the bricks—and the past—still poke through. Director Cong Feng begins and ends the film with sequences in reverse motion—the simplest of cinematic tricks employed to heartbreaking effect. It’s a longing that makes the walls reform, that negates the work of the bulldozer; and it’s cinema as longing, longing as protest.

Similar in tone and subject, Yumen (13) sees Sniadecki team with Chinese artists Huang Xiang and Xu Ruotao for an alternately wry and somber tromp around the ruins of the West China mining town of the title. Filmed on 16mm, and presented as a series of provocatively framed shots of interloping characters dancing and painting and moping inside and outside alluringly abandoned structures, Yumen veers close to ruin porn but does so purposefully, bringing a defiant sense of the poetic and the theatrically absurd to these depopulated spaces. The industry and government may have moved on from Yumen, but here it gets remade into Yumen, an ironic, abstract, campy, homemade art object. By the time the camera tracks backward while a woman in a yellow jacket walks through a still-thriving market—this too shall pass, we can ruefully assume—and hums to the far-off strains of Bruce Springsteen’s “My Hometown,” there’s a sense that any sight gag or audio-visual juxtaposition is fair game, so long as it summons living spirits to this freshly ghosted town.

Satiated Village

The only things more ephemeral than these easily erased physical spaces are, tragically, their former inhabitants. Several young filmmakers represented in the series are concerned with the imminent passing of the older generation—the grandparents who lived through war, reconstruction, famine, and massive cultural upheaval only to be neglected and disrespected by a country dedicated to the new, the young, the proficient. Being so young and yet being fixated on the old is a subtle but significant form of protest, from Yang Pingdao’s The River of Life (14) to Zou Xueping’s Satiated Village (11). The former toggles between staged black-and-white sequences of the filmmaker’s first year as a husband and parent, and faux-weathered color home-movie footage of his extended family. Life and death intermingle uncomfortably, if organically, as nephews and nieces grow up amid remembrances of his long-dead father, and as the birth of his own daughter follows soon after the painful and protracted death of his grandmother. Xueping’s ethos is bare-naked candor, dramatizing his own rage, misogyny, and petulance, and exposing the quotidian ravages of aging without the pillows of restraint or pity. One generation rises while the other fades away, but The River of Life demonstrates how a legacy of shame, guilt, and trauma remains.

Xueping’s The Satiated Village is a sequel to the filmmaker’s The Hungry Village, in which the elderly of her home village of Shandong had recalled their harrowing experiences during the Great Famine of 1960. In the newer film, Xueping invites each of her subjects to view and comment on the earlier one. Though everyone seems to appreciate the honesty and importance of her document, things get testy when the director mentions that the film has been invited to screen abroad. When Xueping implies that their suffering may have been unnecessary, and furthermore allowed by the state, some of these survivors move toward protecting the legacy of Chairman Mao, and by extension, that of the party still in power. That even this small home movie could run afoul of the censors, with its almost tediously scrupulous approach to documenting and worrying over every interaction between filmmaker and subject, should tell you all you need to know about the legitimacy of those reservations. There’s similar unease when Xueping shows the film to the children of Shandong, though just enough idealism among the young viewers to make one optimistic for a positive kind of change.

The Iron Ministry

A similar feeling is engendered by a scene late in The Iron Ministry, in which four young men engage with Sniadecki about the state of things in China. They talk about the high price of real estate in the cities, the changing mores of marriage, the problems with pollution and the environment, whether they’re destined to move out of the country to find a measure of freedom or happiness, and the powerlessness and complacency of the populace (“Everyone’s got steamed buns to eat so there’ll be no revolution, right?” one says, sarcastically). It’s doubtful a word of it could pass muster with the Chinese censors, and it would likely make the elderly residents of Shandong blanch because of the picture of China it exports. But as a Westerner watching from my own perch in a hyper-modernized city, bemoaning the high cost of real estate and perpetually concerned with both imminent environmental catastrophe and my own sense of fulfillment, few sequences in recent cinema have made me feel more connected with the larger world, and more optimistic about how things could evolve in China, or anywhere for that matter. Far from a mere illustration of a formal conceit, or clear evidence of what’s good or bad or too/insufficiently capitalistic/communistic, the scene rather captures people frankly thinking about and wrestling with the reality of their lives. It’s the upside of instability—the benefit of having an open conversation about what matters, of spending time in a place that’s neither here nor there.

Mid-conversation among these young and educated, Sniadecki pans around to watch a man use a bound-twig brush to sweep the car’s voluminous trash into a pile. Whether the young men noticed him as well, or just noted the diversion of the cameraman’s attention, the conversation mutes as the laborer moves past, gathering the wrappers of modern consumption with a medieval tool. The train keeps chugging along to who knows where, which is how the film leaves us as well—in motion, in thought, eyes and ears wide open.

The Iron Ministry is screening at the Museum of Modern Art through August 27. “Cinema on the Edge: The Best of the Beijing Independent Film Festival 2012-2014” is screening in New York at multiple locations through September 13.