Joe Strummer on the set of Walker

“They’re burning the town tonight, aren’t they, Joe?”

“I hope so, man. I like to see things burn. I must admit, I’ve never enjoyed these burning nights. I’ve never worked on a picture with hundreds of extras, muskets, and battle scenes before.”

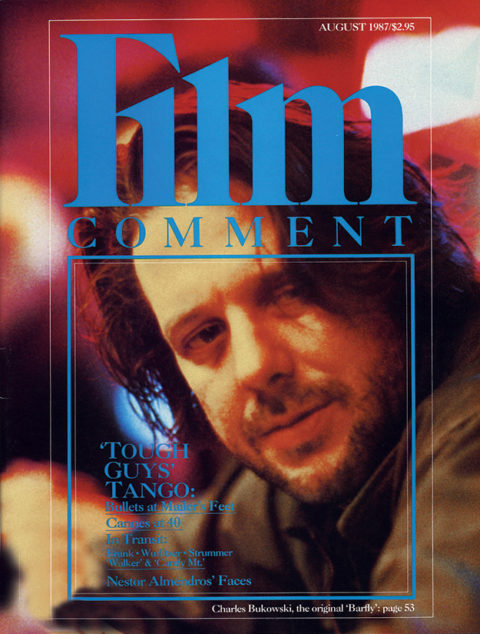

Joe Strummer, ex-leader of the Clash, most incendiary and politically right-on of British punk bands, and burgeoning but reluctant movie star, is propped against a pile of logs in the palace square in Granada, Nicaragua, nipping rum, keeping his own peace, and watching Alex Cox orchestrate a charge of the campesinos for Walker. He’s smoking, too, but I wouldn’t have been surprised if he’d offered me a chaw or slit open a rabbit or two. The thing about Joe is that as Faucet, the scurvy dishwasher in William Walker’s ragged army of “Immortals” who bring a cartoon rogues’ gallery to Cox’s irreverent historical 1850s epic about U.S. intervention in Central America, he is totally unrecognizable. Deadbeat, grimeladen, unkempt shoulder-length hair, mountainman’s beard, a fantastically disreputable army tunic swarming with medal ribbons, a gun not a guitar across his gringo knees—whatever happened to Strummer’s rebel waltz and the spirit of ’76-77? Is this Method acting? Or acting-by-numbers?

“The reason Joe’s a good person to have in the film,” enthuses Cox, “is because he gets incredibly into it and never wants to give up his costume. He gets very upset if he has to give up his guns at the end of the day, but he goes around in the rest of the outfit—the sombrero and the jacket, which he embroidered himself. He doesn’t really change his personality at all.”

Strummer also lived his debut starring part, as the unsmiling Teddy Boy gangster-gunslinger Simms, in Cox’s deliciously awful cheapskate punk spaghetti western, Straight to Hell. He wrangled flies with sugar water applied to the face and practiced not flinching, slept on the set, and twirled his pistol for three weeks until, apparently, he had to bandage his forefinger. “On Straight to Hell, I was pretty nervous, but I found just to concentrate would get me by. Simms was written for me—like he never changes his clothes. All the time I was working on Sid & Nancy and seeing Alex every day, he noticed after a few weeks that I never, ever changed, because at that time I wasn’t certain of anything and decided to stick to the same clothes while I was thinking hard.”

On a rest day on Walker, some of the cast and crew repair to an idyllic beach at San Juan del Sur, anointing their bodies with sunblock against the ferocious heat. But Joe muddies his body in damp sand and tells me to do the same. I guess they didn’t have sunblock in 1855.

If the Clash, initially a cadre of urban guerrillas raging against Britain’s social malaise, later developed their iconography into that of a more internationally alert agitprop army, they always worked hard at enabling their audiences to identity with them. One of my favorite latter-day Clash images, before Mick Jones’s departure signaled the band’s decline, is a simple enough group portrait of Strummer, hand over one eye, Jones, Paul Simonon, and Topper Headon squatting on a railroad track on the sleeve of 1982’s Combat Rock album—with its rap, new American jazz, and Eastern influences on songs about Vietnam, Latin America, and U.S. exploitation, a powerful musical flourish from the last real punks in town. Railroad tracks, though, serve as a reminder that rock stars, like their celluloid equivalents, live parallel lives to their fans, never touching, except by accident or on the distant horizon.

Despite, or because of, the Clash’s championing of Sandinismo on their 1980 album Sandinista!—probably the first time many young Westerners got hip to the FSLN’s revolution—to see the bearded, 34-year-old Joe Strummer sitting reflectively in the dirt in front of the archbishop’s palace in Nicaragua, suddenly seemed like a time warp: “Can I hear the echoes from the days of ’79?”—to adapt a Clash lyric. And him now a film star, too. As Granada burned that night on camera, filling the air with bats and a weird, unearthly fragrance from the damp wood, it would have been hardly any less surprising to me if Marlee Matlin had chosen that moment to turn up on the set, Vivien Leigh–style. Four days later she did, but by then Joe was filming in the jungle.

Was Joe Strummer always going to make it in movies? Will he anyway? Born John Mellors in Turkey on August 21, 1952, he lived in Egypt, Mexico, and Germany before arriving at boarding school in England. As with Orton, John would become Joe; but first, Woody. By the mid-Seventies he was leading an obsessively hard-gigging R&B band, the 101ers, around the London pub circuit. The Clash was formed in 1976, headlined with the Sex Pistols at the 100 Club on Oxford Street in September, and signed to CBS Records in November as punk mushroomed into a national phenomenon.

I first saw Strummer, exactly 10 years prior to the week I saw him in Nicaragua, at Eric’s club in Liverpool. Led by Joe—twitching and barking in the dark, eyes bulging with incredulity at the racial, economic, and class-driven injustices and inequalities in “blank generation” Britain—the Clash, promulgating “White Riot,” was firmly established by then as the militant wing of punk. His was already a face to conjure with. (It could snarl in less theatrical moments, too: I once watched Joe hurl a mike stand across the stage at Brighton’s Top Rank after a searing Clash set in which he had been constantly spat and flobbed on from the front row.) But where was its romantic side, awaiting the liberating influence of a movie camera? In among the Clash’s powerful indictments of American multinationals, heroin, consumerism, 9-to-5 drudgery. Cold War propaganda, and U.S. imperialism in the ensuing years of musical maturity, beginning with the London Calling LP, it was always Mick Jones’s songs that provided the tenderer moments, the odd hint of a love affair.

But there was more time for movies: the Clash’s very own (but subsequently disowned) Rude Roy (80) and a fleeting bit for the whole group in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (82). There was also talk of the band doing music for Scorsese’s abandoned would-be masterpiece, The Gangs of New York, an Irish immigrant story set on the Lower East Side in 1898.

By the fall of 1985, Strummer had hooked up with Alex Cox, the maker of Repo Man, on Sid & Nancy, the punk tragedy documenting an era of which the singer/guitarist was a leader and central icon. Plans to follow that film with a video of a concert tour of Nicaragua by Strummer, Elvis Costello, and the Anglo/Irish punk-folk outfit the Rogues, came to nothing when Cox’s financing fell through. Instead, observing Strummer, young writer/actor Dick Rude, and cinematographer Tom Richmond out of place and out of order in Cannes the following May, Cox lit upon the idea of three hapless killers (Strummer, Rude, and Sy Richardson) turning up in a timeless spaghetti western scenario to take on a gang of coffee-addicted outlaws and their more deadly womenfolk. Almost a “dry run” for Walker, Straight to Hell—its title derived from a bitter, melancholy Clash song on Combat Rock—was shot in Tabernas, near Almeria in southeast Spain (a familiar spaghetti western location where Cox had made the video for Strummer’s “Love Kills” anthem for Sid & Nancy), on $1 million, in three and a half weeks, with a script written by Cox and Rude in three days. It was fueled on energy, alcohol, and a motivating theme of sexual tension.

Straight to Hell

Strummer might just be the best thing in Straight to Hell, which in itself isn’t much of an achievement, although he personally emerged from the shoot a “natural” actor. His sweating deadpan Simms is less a western villain than a drunken British tourist of the Eighties—toppling down a saloon hatch, eyeing the local talent, and combing his hair with a knife dipped in gasoline—but there is an edginess there, a psychotic trigger-happiness, which only glinting shades and a veneer of laconic calm can conceal. He plays it tongue-in-cheek, of course, but he has an unmistakable deftness, a silent, hidden quality, which is also the actor’s recognition that the pauses between words are more powerful than the words themselves.

It seems he had already turned down one chance for stardom as a British delinquent on the loose in Spain. Says Cox: “Joe was offered the part of the young British gangster in The Hit, and then he saw Tim Roth in Made in Britain and said, ’In all honesty, I can’t play this part because there is a better actor than I.’ And he went to Stephen Frears and said, “’Mr. Frears, you must hire Tim Roth.’” And Roth played the part.

In Straight to Hell, meanwhile, Simms, sensing a sexual conquest, goes into the local hardware store ostensibly to buy some nails and is practically raped by the lubricious wife (Jennifer Balgobin) of the proprietor (Miguel Sandoval) when the latter is checking his stock. Later, Simms strikes sparks off the beautiful, red-headed wife of the outlaw leader, played by Sue Kiel, who gives Strummer his first, fiery screen kiss. His dialogue is dry throwaway comedy, but odd close-ups of Strummer frame him listening, watching, waiting, usually for a woman.

One of the actresses on Straight to Hell remarked that Almería Joe resembled a younger, softer Bogart. He does, too, no matter that Granada Joe looks more like Richard Gere in King David. But Strummer’s face is more sensual than lived-in, the lips always parted and the eyes narrowed, the voice more neutral than rasping. He could be a seedier private dick than Mickey Rourke in Angel Heart, but not as cold a killer as, say, Gary Busey in Lethal Weapon: as if we didn’t already know it, there would always be the heart there, the romanticism, in Joltin’ Joe.

Strummer followed Straight to Hell with the tiny role of a security guard on angel dust in Candy Mountain, co-directed by Robert Frank and Walker’s writer Rudy Wurlitzer. The latter is convinced of Strummer’s star potential: “It was very frustrating that Joe had only a small part, because he was very exciting—one wanted more of him. He could be a great star, a major leading man. Somebody will have to give him a big romantic role soon, and I’m sure somebody will.”

Back at Granada, Faucet and Washburn (Rude), his capitalistic partner in the Immortals, are dragged before Walker (Ed Harris) begging for mercy. They are first pardoned and then condemned. Faucet pleads and then breaks free as Darlene (Sharon Barr), a petticoat mercenary in a Sandinista cap, cuts loose at him with her M-16. Strummer’s role in the film is all too brief. But maybe he wants it that way at the moment. Generous on and off the set, responsible more than any other cast and crew member for keeping morale high, he responds to the interview situation warily and sometimes monosyllabically. The following is a sample.

Candy Mountain

How did you become part of Alex’s traveling band of actors?

Dunno, man. Nothing better to do, I suppose.

What do you think are his special attributes as a director?

What’s special about him is that he’s still young and hasn’t become a big bureaucrat in getting the money together and mounting big productions. You’re lucky if you can get to your fifth film without being ground down to hamburger meat. Alex is still the same guy I can imagine loping along the Venice beach in L.A. after graduating from film school. He’ll listen to any crazy idea from anybody. And he keeps the Hollywood dross away from him—he knows it’ll contaminate him.

So how do you see your involvement in films—if any—shaping up?

I don’t know. I have directed a film myself. It was called Hell West End, a black-and-white 16mm silent movie, and it was a disaster. Luckily, the laboratory that held the negative went bankrupt and destroyed all the stock, so the world can breathe again.

That was like a dry run for me—I managed to shoot it without a script. God knows what it was about. I was the only other one who knew, and I’m not telling. But when I get the bug back, I might try another one. I think film directing is something you have to build up to—make a few bum films like they do in college. No one has to see it, and then you get your hands on a bit of dough and a good idea, and with a bit of luck you can swing it along from there, learning as you go. Only an idiot would just attempt to walk in and try and direct a picture.

What is your view on current movies?

I think there’s real life in that Greenwich Village scene. When I was in Cannes last year, I only saw two films—Spike Lee’s and Jim Jarmusch’s. Those are real movies, but I didn’t go and see The Mission and all those other adverts for Hollywood. But what’s happening in the Village will start to happen in music soon, I think.

What do you plan to do with your music career?

I’m helping Mick Jones out now and again with Big Audio Dynamite’s stuff, but I don’t know what to do for myself. I don’t know whether to go back to rocking or not.

Are you going to be doing music for the film with some of the other musicians who are down here?

No. I don’t really talk to them [laughs]. We all live together in a house on the outskirts of town. I’m gonna try and do the music for the film after the shoot. I hope I can do it here—the environment dictates the way you are.

Is the Clash over for good?

Yeah, I think so.

What are your feelings about filming in Nicaragua?

For me, it was a long winter in Britain and pretty depressing, right? So I was feeling generally fed up, and I came down here and it was just what I needed—to see people who’ve really got nothing, but are coping and laughing and still enjoying life. On the backlot here in Granada, I was walking along with another actor, Jack Slater, and we saw these kids playing baseball with homemade balls and hand-carved bats, and basketball with a cardboard box attached to a telegraph pole, and there was a little girl with a plastic bag filled with air, which she was throwing up and catching. And even though they had nothing, they were all having a really good time.

I’ve been here about two months, and in that time you realize that this is just a normal country that happens to have a leftist government that is trying to sort its problems out. Things aren’t so black and white here as I’ve found from looking from far away with a pro- or anti-Sandinista, or pro- or anti-Reagan or -Thatcher stance. When you get here, all that hardly seems to make any sense. It just seems like that the country’s a helluva lot better off than it was under Somoza, when there wasn’t any education or medical care and half the population was kept illiterate. Compared to those days, they’ve made vast progress—any human being would surely be in favor of that.

What about the progress in Nicaragua since the revolution?

There are many factions inside the Sandinistas, and they’ll probably have little power struggles and adjust. It’ll probably bubble down to some kind of even keel, and it’ll always be more central than extreme Maoist. It’s a pity the U.S.A. doesn’t trade with countries like Nicaragua. I don’t think the U.S.A. will invade—I think this is Reagan’s personal obsession, and as he passes away so the obsession will, too.

Did you ever want to take your role as a punk figurehead any further, in a political sense maybe?

No. I just know I could never be any good. I think you have to know yourself fully, make your decisions on what you find out. I just know I’d never be a good committeeman or submit to any kind of discipline.

You’ve been in three films in quick succession now. Do you plan to develop your career as an actor?

Not really. This is the beginning of the end. It’s too difficult.